Incense drifting through ancient cedars. Saffron-robed monks, limbs a blur of movement, making quick work of imagined enemies. The boing of a giant bronze bell calling the faithful to prayer.

This is the scene at the fabled Shaolin Temple, a cradle of kung fu and Zen Buddhism nestled in the forests of Henan Province, China, where legend has it monks have trained in martial arts for centuries. However, in recent days, another sound has been wafting across its hallowed grounds: the snickering of tourists trading the latest news about the Shaolin Temple abbot and his reportedly less than virtuous ways.

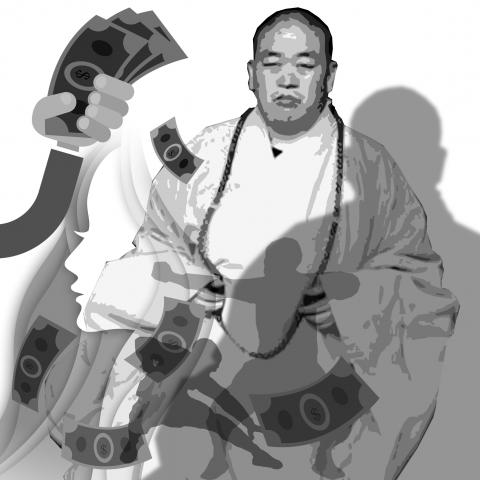

Over the past week, much of China has been transfixed by salacious allegations that the famed abbot, Shi Yongxin (釋永信), known as “China’s CEO monk” for transforming Shaolin into a global commercial empire, is a swindler and serial philanderer who secretly fathered children with two of his lovers, vows of celibacy notwithstanding.

Illustration: Tania Chou

The accusations — new tidbits have appeared almost daily in the Chinese media — are mostly based on documents released by a self-described former monk at the temple who says the abbot owns a small fleet of fancy cars, has embezzled millions of dollars from a temple-run corporation and funneled some of the cash to a mistress now living in Australia.

Beyond the obvious legal repercussions, the abbot’s apparent lust for women, money and bling runs counter to the virtues of chastity and austere living that he has long sought to personify as one of the most prominent figures in Chinese Buddhism. To his growing legion of critics, the scandal has heightened public cynicism about a society in which greed and crass materialism often seem to trump morality, especially among those in positions of power.

‘SEEKER OF JUSTICE’

The informer, a mysterious figure using a name that translates as “seeker of justice,” has told reporters he is fed up with the abbot’s hypocrisy and wants to see the “grounds of Shaolin purified again.”

He declined interview requests and has yet to appear in public, saying he is afraid for his safety following threats from what he called “Shi Yongxin’s henchmen.”

“We want the outside world to know that the Shaolin abbot, using Buddhism as a cloak, is a maniacal womanizer and corrupt ‘tiger’ who brazenly exploits Shaolin’s assets and tarnishes its reputation,” he wrote in a statement last week that pleaded for a government investigation.

Among the evidence he has made public to support his accusations are police depositions and photographs of a woman said to be one of the abbot’s lovers, a Shaolin nun who appears dressed in brown monastic robes while holding the baby she says was fathered by Shi. Another supposed mistress claims to have physical evidence of his lechery: semen, collected in a condom, which she sent to a doctor for safekeeping. Over the weekend, she used a social media account to post a photo of the underwear she says she wore during sex with the abbot.

During a visit to the temple last week, the modest gray-brick pavilion where Shi lives and works was padlocked, and monastery officials declined interview requests. In a statement posted online, they called the allegations against Shi “vicious, groundless libel.”

Local police officials say they have opened an investigation, perhaps moved by the media maelstrom and a public finger wag by the powerful State Administration for Religious Affairs, which warned that the scandal threatened to tarnish Chinese Buddhism.

COMMERCIAL REVIVAL

Critics have complained for years that Shi has overcommercialized Shaolin through product licensing and overseas franchises, including plans for a US$300 million luxury Shaolin kung fu resort and golf course in southeastern Australia.

Like the paying tourists who flock to Shaolin’s hourly “fighting monks” acrobatic show, other controversies have come and gone, including reports that the monastery spent more than US$400,000 on “luxury toilets” and an initial public stock offering that was scuttled amid criticism that monks sworn to asceticism should not be playing the stock market.

News accounts have also detailed Shi’s taste for Apple products and gold-filament robes — all gifts, he said — and a 2011 Xinhua report said the authorities were investigating claims that he managed to escape prosecution after being caught in a brothel raid.

Through it all, the abbot has remained stoic, refusing to respond to allegations of impropriety while brushing off requests to release details of the monastery’s finances, which include those of Shaolin Intangible Assets Management, a corporation that invests in seven Buddhist-themed enterprises and is largely owned by him.

“If these things are problems, they would have become problems by now,” he told the BBC elliptically during a visit to London last year.

A pudgy, soft-spoken man with a round, shaved head, Shi, 50, is alternately lionized in the Chinese media for reviving the 1,500-year-old monastery complex after decades of desecration and neglect, and criticized for his mercantile approach to its management.

In interviews, he has described the business deals and his globe-trotting ways as necessary to promote Buddhism, especially Shaolin’s unique brand of martial arts, mysticism and faith.

“If China can import Disney resorts, why can’t other countries import the Shaolin Monastery?” Xinhua quoted him as saying in March amid criticism over the Australia project. “Promoting culture abroad is a very dignified undertaking.”

CCP FAVOR

Even if officially atheist, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has come to appreciate Shaolin’s global profile and its ability to generate revenue. Judging from the parade of officials who have visited in recent years, many also evidently believe in the mythological protective powers of Shaolin’s fighting monks, a reputation dating from the seventh century, when, as the story goes, a band of 13 monks saved a Tang Dynasty prince from a predacious warlord.

Appreciative officials have returned the favor, giving Shi a US$125,000 luxury vehicle and anointing him as a representative to the country’s ceremonial legislature, the National People’s Congress. His other political sinecure is a top job with the state-run Buddhist Association of China.

Shi’s defenders say successful people invariably draw enemies. Li Xiangping (李向平), director of the Religion and Society Research Institute at East China Normal University, said the critics had misunderstood his role as a bridge between Buddhism and the secular world, especially a government that has the ultimate say over religious affairs in China.

“They think monks should just study scripture really hard and sit meditating morning and night,” Li said. “If you really want to promote Buddhism and influence society, you have to interact with the society.”

Amid a party campaign against corruption and gluttony that has toppled scores of powerful figures, the fact that the story has remained alive in the tightly controlled state news media for so many days does not bode well for Shi.

On Monday, news outlets gleefully reported that he failed to show up in Thailand over the weekend for a previously scheduled martial arts performance because he was “tied up” with the investigation.

‘VIRTUOUS MAN’

However, at the heart of Shaolin Inc, home to 400 resident monks and where thousands of students study martial arts in private academies that line the main road to town, support for Shi remains strong.

Recently, a group of 30 monks released a public letter rejecting the allegations against him, and even the trinket vendors wave away the innuendo.

“You won’t find a more virtuous man,” said Wang Daling, 50, a tour guide who has been leading groups through the temple complex for two decades.

However, many tourists were not buying the denials.

“Just the sight of his fleshy face to me suggests he’s guilty,” said Li Yanan (李陽南), 24, an engineering student on a visit from nearby Shandong Province. “Monks aren’t supposed to be so fat.”

Still, few thought Shaolin would suffer lasting damage given the temple’s popularity in China and abroad.

“The more gossip about Shaolin, the more tourists will come,” said Zhang Jianzhen (張建珍), 32, a snack vendor whose concession sells US$1.50 bottles of water, a 400 percent markup over those sold outside Shaolin’s gates.

“That can only be good for business,” he said.

We are used to hearing that whenever something happens, it means Taiwan is about to fall to China. Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) cannot change the color of his socks without China experts claiming it means an invasion is imminent. So, it is no surprise that what happened in Venezuela over the weekend triggered the knee-jerk reaction of saying that Taiwan is next. That is not an opinion on whether US President Donald Trump was right to remove Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro the way he did or if it is good for Venezuela and the world. There are other, more qualified

This should be the year in which the democracies, especially those in East Asia, lose their fear of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) “one China principle” plus its nuclear “Cognitive Warfare” coercion strategies, all designed to achieve hegemony without fighting. For 2025, stoking regional and global fear was a major goal for the CCP and its People’s Liberation Army (PLA), following on Mao Zedong’s (毛澤東) Little Red Book admonition, “We must be ruthless to our enemies; we must overpower and annihilate them.” But on Dec. 17, 2025, the Trump Administration demonstrated direct defiance of CCP terror with its record US$11.1 billion arms

The immediate response in Taiwan to the extraction of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro by the US over the weekend was to say that it was an example of violence by a major power against a smaller nation and that, as such, it gave Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) carte blanche to invade Taiwan. That assessment is vastly oversimplistic and, on more sober reflection, likely incorrect. Generally speaking, there are three basic interpretations from commentators in Taiwan. The first is that the US is no longer interested in what is happening beyond its own backyard, and no longer preoccupied with regions in other

As technological change sweeps across the world, the focus of education has undergone an inevitable shift toward artificial intelligence (AI) and digital learning. However, the HundrED Global Collection 2026 report has a message that Taiwanese society and education policymakers would do well to reflect on. In the age of AI, the scarcest resource in education is not advanced computing power, but people; and the most urgent global educational crisis is not technological backwardness, but teacher well-being and retention. Covering 52 countries, the report from HundrED, a Finnish nonprofit that reviews and compiles innovative solutions in education from around the world, highlights a