Scan the headlines about modern day slavery in Qatar, forced labor in Uzbekistan, a ban on trade unions in Swaziland, a draconian anti-gay law in Uganda and widespread economic, and social discrimination against women — as well as millions of children who are abused, neglected or exploited — and it is hard to argue that global corporations are being asked to do too much to protect human rights.

However, as the number of human-rights demands placed on businesses — and particularly on global companies with supply chains in poor countries — continues to escalate, there is a risk that governments might be let off the hook. After all, governments are obligated, if not always willing or able, to protect human rights.

This is one of the themes that arose during last week’s UN Forum on Business and Human Rights, an annual meeting that attracted about 2,000 people from businesses, government, labor groups and nonprofit organizations to the sprawling Palais de Nations compound in Geneva, Switzerland. The meeting comes three years after the UN endorsed a set of guiding principles on business and human rights, which define the private sector’s responsibilities in broad terms.

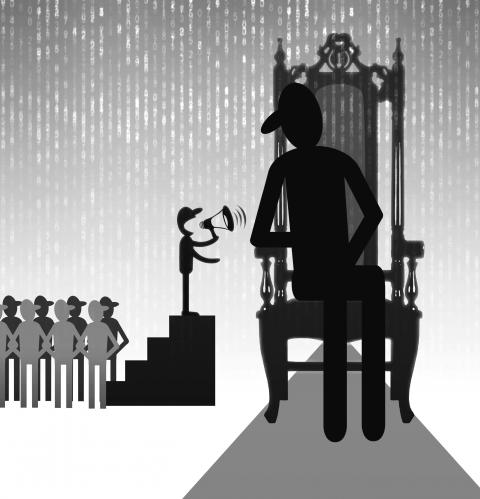

Illustration: Yusha

One of the difficulties for companies taking on the responsibility of protecting human rights is that the definition of the term “human rights” is infinitely expandable. The UN says it includes labor rights, gender rights, children’s rights, gay rights, cultural rights, freedom of expression, the right to food and water, land rights, indigenous people’s rights, the rights of development and self-determination, all of which are interrelated, interdependent and indivisible.

One panel at this week’s conference pondered the question: “Does the world need a human rights-based convention on healthy diets?”

It is no wonder some companies duck and hide what they are doing to protect human rights.

A second problem is that many businesses do not have the expertise or the resources to do much about human rights beyond their own corporate walls and supply chains. Neither are they accountable to the public, as governments should be.

Yet the reality is that over the past decade or so, governments in China, Bangladesh and Indonesia, among other places, have in effect outsourced their labor law enforcement to global corporations. Dozens of retailers and brands have erected extensive and expensive infrastructures of workplace standards, audits, inspections and reports to improve factory conditions — with mixed results, at best. In the long run, it does not make sense to leave it to Apple and Walmart to guard the rights of factory workers halfway round the world.

That is not to say, of course, that businesses cannot do more. Several prominent chief executives who spoke at the forum — Unilever chief executive Paul Polman, Nestle chief executive Paul Bulcke and Safaricom chief executive Bob Collymore — embraced the idea that companies need to do more, not less, on human rights.

“We must work harder to promote human rights, not just respect them,” Polman said.

Bulcke pointed with pride to the work that Nestle is doing to help improve the lives of 750,000 farmers in its supply chains. For his part, Collymore talked about providing tablets to help educate thousands of children in a refugee camp in Dadaab, Kenya.

Their efforts were praised by, among others, International Trade Union Confederation general secretary Sharan Burrow. However, she pointedly said that hundreds of millions of poor workers are not fortunate enough to be associated with companies like Unilever.

“Today’s global supply chains are characterized by exploitation,” she said.

Burrow urged big companies to work together with labor groups and non-governmental organizations to press for higher minimum wages in emerging markets. In Cambodia, for instance, the minimum wage was recently raised from US$100 to US$128 per month, but only after a long campaign during which militant workers clashed with police.

Even if responsible companies voluntarily agree to pay more, they can be undercut by less scrupulous competitors, Burrow said. Only the governments can establish a set of rules that apply to all.

Put another way, one of the most important things that companies can do to promote human rights is to become increasingly active in the public policy arena, by lobbying governments to respect human rights — pushing for press and Internet freedom in China, for example, or a higher minimum wage in Vietnam.

The trouble is, not many companies are willing to lobby for more regulation, said Georg Kell, executive director of the UN Global Compact, a corporate sustainability initiative.

With a few exceptions, “the big industry associations are still fighting old ideological battles,” opposing any interference with unfettered markets, he said.

Moreover, it is difficult to get chief executives of big companies to cooperate, even around human rights issues.

“It’s not in the mindset of these highly competitive alpha guys,” he said.

That said, cooperative efforts are emerging. The most promising is in Bangladesh where, in response to the Rana Plaza garment factory collapse, garment brands and retailers formed a pair of coalitions, the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety and the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, to improve factory conditions.

Equally important is that the US government, European Commission, International Labour Organization and the Bangladeshi government have signed a sustainability compact aimed at, among other things, strengthening labor laws in Bangladesh.

The goal is to duplicate the kinds of government institutions and processes that work reasonably well, most of the time, to protect the human rights of workers in the US and the EU.

Business has a role to play.

However, as veteran Pakistani lawyer and human rights activist Hina Jalani reminded the UN group: “It is the fundamental obligation of states to protect citizens against exploitation and degradation.”

The image was oddly quiet. No speeches, no flags, no dramatic announcements — just a Chinese cargo ship cutting through arctic ice and arriving in Britain in October. The Istanbul Bridge completed a journey that once existed only in theory, shaving weeks off traditional shipping routes. On paper, it was a story about efficiency. In strategic terms, it was about timing. Much like politics, arriving early matters. Especially when the route, the rules and the traffic are still undefined. For years, global politics has trained us to watch the loud moments: warships in the Taiwan Strait, sanctions announced at news conferences, leaders trading

The saga of Sarah Dzafce, the disgraced former Miss Finland, is far more significant than a mere beauty pageant controversy. It serves as a potent and painful contemporary lesson in global cultural ethics and the absolute necessity of racial respect. Her public career was instantly pulverized not by a lapse in judgement, but by a deliberate act of racial hostility, the flames of which swiftly encircled the globe. The offensive action was simple, yet profoundly provocative: a 15-second video in which Dzafce performed the infamous “slanted eyes” gesture — a crude, historically loaded caricature of East Asian features used in Western

Is a new foreign partner for Taiwan emerging in the Middle East? Last week, Taiwanese media reported that Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Francois Wu (吳志中) secretly visited Israel, a country with whom Taiwan has long shared unofficial relations but which has approached those relations cautiously. In the wake of China’s implicit but clear support for Hamas and Iran in the wake of the October 2023 assault on Israel, Jerusalem’s calculus may be changing. Both small countries facing literal existential threats, Israel and Taiwan have much to gain from closer ties. In his recent op-ed for the Washington Post, President William

A stabbing attack inside and near two busy Taipei MRT stations on Friday evening shocked the nation and made headlines in many foreign and local news media, as such indiscriminate attacks are rare in Taiwan. Four people died, including the 27-year-old suspect, and 11 people sustained injuries. At Taipei Main Station, the suspect threw smoke grenades near two exits and fatally stabbed one person who tried to stop him. He later made his way to Eslite Spectrum Nanxi department store near Zhongshan MRT Station, where he threw more smoke grenades and fatally stabbed a person on a scooter by the roadside.