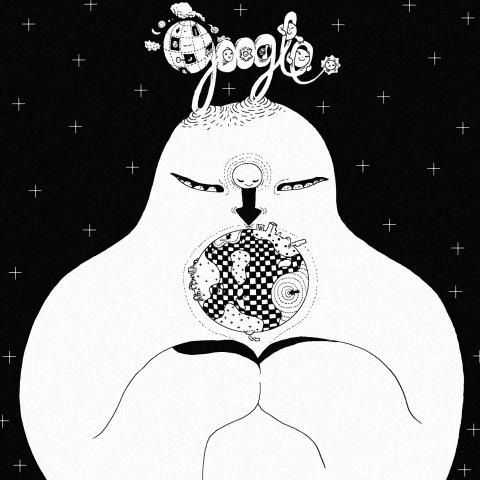

Eight years ago, Google bought a cool little graphics business called Keyhole that had been working on 3D maps. It turned out to be a very smart move.

Along with the acquisition came Brian McClendon, a tall and serious Kansan, who had supplied high-end graphics software used in films including Jurassic Park and Terminator 2.

Today, McClendon is Google’s Mr Maps — presiding over one of the fastest growing areas in the search giant’s business; one that has recently left rival Apple embarrassed and threatens to make Google the most powerful company in mapping the word has ever seen.

Google is throwing considerable resources into building what is arguably the most comprehensive map ever made.

“It’s all part of Google’s self-avowed mission to organise all the world’s information,” McClendon said. “You need to have the basic structure of the world so you can place the relevant information on top of it. If you don’t have an accurate map, everything else is inaccurate,” he says.

It is a message that will make Apple cringe. The company triggered outrage when it pulled Google Maps off the latest version of its iPhone software for its own bug-riddled and often wildly inaccurate map system.

“We screwed up,” Apple boss Tim Cook said last week.

McClendon won’t comment on when and if Apple will put Google’s application back on the iPhone. Talks are ongoing and he is at pains to point out what a “great” product the iPhone is. It will be a huge climbdown if they have to reuse Google. In the meantime, what McClendon really cares about is building a better map.

This is not the first time Google has made a landgrab in the real world, as the publishing industry will attest. Its ambitions in maps could be bigger, more far reaching and more controversial. For a company developing driverless cars — the governor of California signed a law last month to allow driverless cars on the state’s roads from 2015 — and wearable computers in the form of glasses. Maps are a serious business. There is no doubting McClendon’s vision. His car licence plate reads: ITLLHPN.

Until the 1980s maps were still largely a pen and ink affair, then mainframe computers allowed the development of geographic information system software (GIS) able to display and organise geographic information in whole new ways.

By 2005, when Google launched Google Maps, computing power allowed the software to go mainstream. Maps were about to change the way we find a bar, a parcel or even a story — Washington’s homicidewatch.org, uses Google Maps to track fatal attacks across the city. Now the rise of mobile devices has pushed mapping into everyone’s hands and to the forefront in the battle of the tech giants.

About 20 percent of Google’s queries are now “location specific.” The company doesn’t give an exact number, but on mobile the percentage is “even higher,” McClendon said.

Google’s approach to better maps is about layers. It started with an aerial view and added Street View in 2007. Its ground level photographic map, snapped from its own fleet of specially designed cars, now covers 8 million kilometers of roads. Google is not stopping there. The company has put cameras on bikes to cover remote trails, and you can tour the Great Barrier Reef thanks to diving mappers. Luc Vincent, the Google engineer known as “Mr Street View,” carried a 18kg pack of snapping cameras down to the bottom of the Grand Canyon and then back up along another trail as fellow hikers excitedly shouted “Google, Google” at the man with the space-age backpack.

Now the company has two projects called Ground Truth, which allows people to correct errors online, and Map Maker, which allows them to build their own maps.

In the western US, Ground Truth and Map Maker have been used to add a missing road, correct a one-way street, and generally improve what’s already there. In Africa, Asia and other less well covered areas of the world, Google is helping people literally put themselves on the map.

In 2008 it could take six to 18 months for Google to update a map. The company would have to go back to the firm that provided its map information and get people to check it, make corrections and send it back to Google.

“At that point we decided we wanted to bring that information in-house,” McClendon said.

Google now updates its maps hundreds of times a day. Anyone can correct errors they find through Ground Truth. Google checks and relies on other users to spot mistakes.

Thousands of people every day use Google’s Map Maker to recreate their world online, said Michael Weiss-Malik, engineering director at Google Maps. Pakistanis living in the UK have basically built the whole map of their native country, he said. Using aerial shots and local information, people have created the most detailed maps that have ever existed of cities such as Karachi. It is a labor-intensive process. It is also the fastest updating map in history. Google even maintains a live stream where you can watch edits happening in real time.

“The fact is, the real world is changing. Chasing the real world is our measure. It’s not how we compare to our competitors, it’s how we compare to the real world,” McClendon said.

It is not just the great outdoors that Google wants to map. The company is increasingly interested in mapping indoors. McClendon was recently in Tokyo’s Shinjuku station, the world’s busiest transport hub. Shinjuku has 35 platforms, well over 200 exits and is used by more than 3.64 million people a day. Google has it mapped.

Once he has his map, McClendon says, the real challenge is what not to show. The London Underground map, a design classic that is easy to read, is an example of the old world idea of a map.

“They reduced it down to the most readable form that still contains all the information. They’ve done that so everybody can read it. But imagine if you saw the London underground system only as you use it,” he said. “Your map would let you know which lines are busy, change to reflect your working pattern, the time of day, what you do at the weekend. The ability to remove information allows you space to provide another level of more personalized information. A map that tries to answer every question for every person is effectively unreadable.”

But you can only do that once you have all the information people might need.

“You need to have the basic structure of the world so you can place the relevant information on top of it. If you don’t have an accurate map, everything else is inaccurate,” he said.

Google’s domination of mapping has some people worried. The company has run into difficulties regarding privacy, not least in Germany, where Google abandoned Street View after clashes with the authorities. It was fined in the US after it was discovered that Street View cars were collecting private information from people’s wireless networks.

Steven Romalewski, director of the mapping service at the City University of New York’s Center for Urban Research, said Google had opened up the new era of mapping, yet he worries there isn’t enough competition.

“I wouldn’t want to see one entity controlling the base map,” Romalewski said.

“There will always be multiple providers. I don’t see us effectively owning the map,” McClendon said. “We are making a version of the world, as accurate as we can make it.”

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) has its chairperson election tomorrow. Although the party has long positioned itself as “China friendly,” the election is overshadowed by “an overwhelming wave of Chinese intervention.” The six candidates vying for the chair are former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), former lawmaker Cheng Li-wen (鄭麗文), Legislator Luo Chih-chiang (羅智強), Sun Yat-sen School president Chang Ya-chung (張亞中), former National Assembly representative Tsai Chih-hong (蔡志弘) and former Changhua County comissioner Zhuo Bo-yuan (卓伯源). While Cheng and Hau are front-runners in different surveys, Hau has complained of an online defamation campaign against him coming from accounts with foreign IP addresses,

Former Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmaker Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) on Saturday won the party’s chairperson election with 65,122 votes, or 50.15 percent of the votes, becoming the second woman in the seat and the first to have switched allegiance from the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to the KMT. Cheng, running for the top KMT position for the first time, had been termed a “dark horse,” while the biggest contender was former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), considered by many to represent the party’s establishment elite. Hau also has substantial experience in government and in the KMT. Cheng joined the Wild Lily Student

When Taiwan High Speed Rail Corp (THSRC) announced the implementation of a new “quiet carriage” policy across all train cars on Sept. 22, I — a classroom teacher who frequently takes the high-speed rail — was filled with anticipation. The days of passengers videoconferencing as if there were no one else on the train, playing videos at full volume or speaking loudly without regard for others finally seemed numbered. However, this battle for silence was lost after less than one month. Faced with emotional guilt from infants and anxious parents, THSRC caved and retreated. However, official high-speed rail data have long

Starting next year, drivers older than 70 may be entitled to a monthly NT$1,500 public transportation and taxi subsidy if they relinquish their driver’s license, the Ministry of Transportation and Communications announced on Tuesday. The measure is part of a broader effort to improve road safety, with eligible participants receiving the subsidy for two years. The announcement comes amid mounting concern over traffic safety in Taiwan. A 2022 article by CNN quoted the name of a Facebook group devoted to the traffic situation called “Taiwan is a living hell for pedestrians,” while Berlin-based bne IntelliNews last month called it a “deadly