In a spacious but frugal office in Kuwait, a glossy catalogue lists the dozens of reasons why Kuwait and Iraq are still at daggers drawn after all these years.

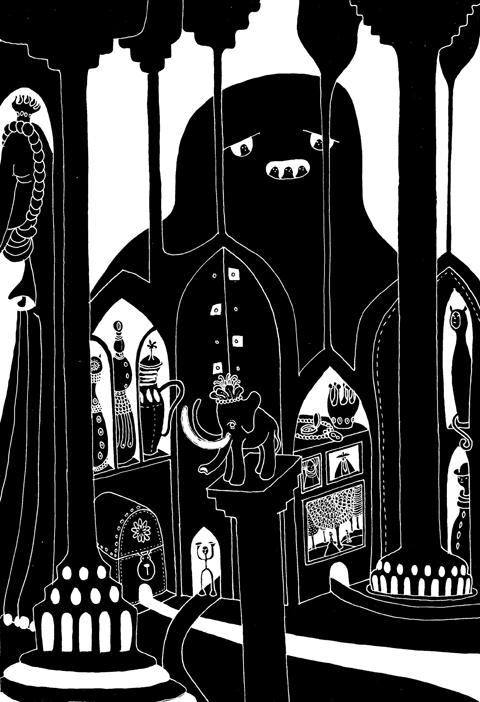

Sheikha Hussa Salem al-Sabah thumbs through the pages of the booklet, pointing out the most egregious cases — page upon page of priceless treasures looted by former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein’s invading army 20 years ago and still missing: a dazzling 234-carat emerald the size of a paperweight; a slightly smaller gem inscribed with exquisite Arabic calligraphy; Moghul-era ruby beads.

“The Iraqis still don’t understand the damage they did to us, not just financially, but for our souls,” says the daughter-in-law of Kuwaiti Emir Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah, who maintains the dynasty’s heirlooms. “It was emotionally wrenching and still is.”

Though many of the priceless treasures have been returned to the collection in the bitter decades since, up to 57 remain missing — perhaps lost for ever. At the National Museum across town, they report that the whereabouts of another 487 treasures remain unknown.

Many of the pieces, Kuwaitis believe, now form the core of private collections in post-Saddam Iraq and around the Arab world. To the victims of the 1990 invasion, they remain the central reason of a failure to close the unfinished business of the first Gulf war — just as the second one is beginning to wind down.

In the seven years since Saddam was ousted, Iraq has been obliged to settle UN-prescribed debts of US$43 billion and compensation to private families totaling several hundred million dollars more, before being welcomed as a full-fledged member of the so-called community of nations.

It is a burden that has proven difficult to bear for a brittle state still ravaged by war and chaos and deeply resentful of the fact that Kuwait was not invaded in the name of the current regime in Iraq.

To Iraq’s wealthy southern neighbor though, the desire to reclaim what was lost still burns strong.

“This is about principle,” Sheikha Hussa said. “This is part of Kuwait’s rights and we will continue to press them.”

At the National Museum, lost artifacts mainly date from the Moghul dynasty and include around 20 gold bracelets, necklaces and ankle rings, pottery, arrow heads and Korans.

Staff handed over a list of stolen loot and mentioned a theory often discussed in Kuwait that much of what was stolen remains in a warehouse north of Baghdad, where it is being used as leverage in any eventual settlement between the two countries.

Three months of inquiries by the Guardian with officials in Iraq’s government, military and police seem to rule out that there is such a repository.

“Anything that was stolen was taken to Saddam’s palaces and the offices of his high officials,” one Kuwaiti member of parliament said. “There were antique cars stolen by Uday [Hussein, Saddam’s psychopath son] that were sold in Europe at auction, paintings and heirlooms, but after the American invasion it was a free-for-all. Everything was stolen again then and there was no control over who took it, or where it went.”

Between the first and second Gulf wars, there were attempts by Saddam’s regime to put things right, with Kuwaiti officials being invited to the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad to reclaim stolen Kuwaiti pieces.

The private art world also turned up the occasional treasure. In 1996, a jewel-encrusted Moghul dagger, which had been at Sotheby’s, was returned to the Dar-al-Athar collection. Financial compensation has been paid, according to Sheikha Hussa, but the repatriation of priceless pieces has been rare.

Two years ago, parts of a giant archive of Kuwait’s history, known as the Prince’s Archive, were returned from Baghdad after being kept in the home of a civil servant who had little idea of the value of his souvenirs.

Iraq hopes that a steady repayment of the billions it owes will boost its credentials and stop Kuwait from pressing claims through international courts for the seizure of Iraqi assets.

Twice in recent months the state-owned Kuwait Airways has moved to seize an Iraqi Airways plane that had landed in London as part of a new passenger route from Baghdad. That action has led Iraq to suspend the route only weeks after it was opened.

Iraq’s monthly repayments are pegged by the UN at 5 percent of its oil revenue.

“Last month they paid US$520 million as part of the United Nations Compensation Commission obligations,” said the chairman of a Kuwaiti public authority established to process compensation claims from Iraq’s invasion. “They have been cooperating with us in meetings lately, but it takes time, it will need another generation to forget. There are also the remains of fallen soldiers and POWs yet to be returned.”

In Baghdad, Iraqi parliamentary speaker Ayad al-Sammaraie said things were now moving quicker than at any other time since 1990.

“Now both countries are willing to sort things. But there is still a remaining bitterness. Resolving this is very complicated and needs a realistic perspective,” he said.

“Our fishermen are worried at repeated interceptions by the Kuwaitis in the Gulf. Our farmers in the south are worried about border claims. And we are concerned about having good relations again,” he said.

Asked about the ancient treasures that in some ways hold the key to goodwill, he said: “There was no [sovereign] Iraq from 2003 for three years and we had no ability to look for them. But really, Iraq is sincere and willing to return them.”

China has not been a top-tier issue for much of the second Trump administration. Instead, Trump has focused considerable energy on Ukraine, Israel, Iran, and defending America’s borders. At home, Trump has been busy passing an overhaul to America’s tax system, deporting unlawful immigrants, and targeting his political enemies. More recently, he has been consumed by the fallout of a political scandal involving his past relationship with a disgraced sex offender. When the administration has focused on China, there has not been a consistent throughline in its approach or its public statements. This lack of overarching narrative likely reflects a combination

Father’s Day, as celebrated around the world, has its roots in the early 20th century US. In 1910, the state of Washington marked the world’s first official Father’s Day. Later, in 1972, then-US president Richard Nixon signed a proclamation establishing the third Sunday of June as a national holiday honoring fathers. Many countries have since followed suit, adopting the same date. In Taiwan, the celebration takes a different form — both in timing and meaning. Taiwan’s Father’s Day falls on Aug. 8, a date chosen not for historical events, but for the beauty of language. In Mandarin, “eight eight” is pronounced

US President Donald Trump’s alleged request that Taiwanese President William Lai (賴清德) not stop in New York while traveling to three of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies, after his administration also rescheduled a visit to Washington by the minister of national defense, sets an unwise precedent and risks locking the US into a trajectory of either direct conflict with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) or capitulation to it over Taiwan. Taiwanese authorities have said that no plans to request a stopover in the US had been submitted to Washington, but Trump shared a direct call with Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平)

It is difficult to think of an issue that has monopolized political commentary as intensely as the recall movement and the autopsy of the July 26 failures. These commentaries have come from diverse sources within Taiwan and abroad, from local Taiwanese members of the public and academics, foreign academics resident in Taiwan, and overseas Taiwanese working in US universities. There is a lack of consensus that Taiwan’s democracy is either dying in ashes or has become a phoenix rising from the ashes, nurtured into existence by civic groups and rational voters. There are narratives of extreme polarization and an alarming