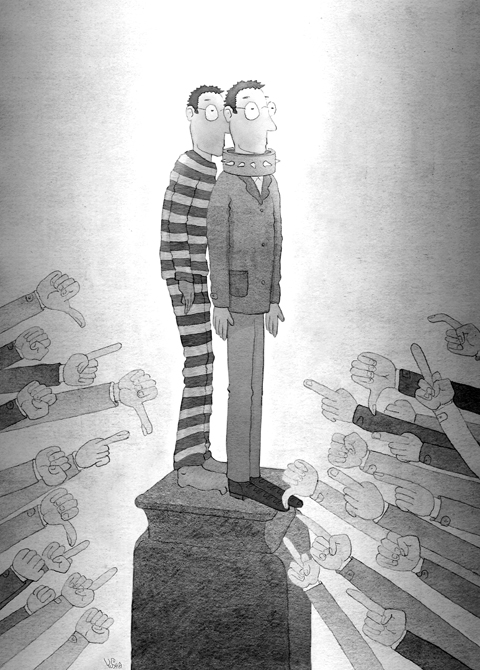

For some imprisoned in the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, getting out of jail has not meant freedom.

Imprisoned at 21 for destroying a videotape of clashes between soldiers and Beijing residents, Zhang Yansheng (張延生) spent nearly 14 years in prison before his life sentence was commuted in 2003. He served another five years of parole, barred from media interviews, publishing, free speech or travel.

Now he’s out of prison, but he cannot find steady work and shares his elderly mother’s apartment and meager pension.

Finally able to tell his story at 41, Zhang says: “Most of us were in our 20s, just starting out, and then our lives were ruined, just like that ... Now, after so many years we get out and no one cares. There is no one to look after us.”

While most Chinese have moved beyond the events of 1989 — either because government taboos prevent discussion or because they’re wrapped up in the boom that has brought prosperity to many — Zhang lives with his decision every day.

He cannot find steady work because he was a convict, and scrapes by on his mother’s US$150-a-month pension. His niece and nephew don’t know he was in jail; they were told he was in the army. The Beijing of his youth is gone.

Unfamiliar buildings and the sea of new cars left him disoriented when he first got out; he felt lost and frequently scared in his old neighborhood. People had changed too.

“We were all very much the same back then. Nobody was better than anybody else and people put other people’s feelings first,” Zhang said at a cafe near his apartment. “That feeling of camaraderie, of helping each other is all gone. You’re chatting, someone says ‘Can you help me with this or that?’ The first response is ‘How much will you pay me?’”

Bald and slim, with a missing tooth, Zhang looks tough but speaks softly.

At the time of his arrest, Zhang was an usher at the Beijing Exhibition Center, an ornate 1950s-era communist landmark. His former co-workers now have families, meager pensions and health insurance. Zhang has none of that. He was released from jail with stern warnings to avoid trouble and nothing else, he said.

Like many of those given the harshest sentences for the Tiananmen protests, Zhang was not a student or a protest organizer. He was one of the working class youths who burned army trucks, fought with soldiers or stole equipment.

On June 4, 1989, he stole a video filmed by paramilitary guards that showed residents trying to block the army’s advance on demonstrators occupying Tiananmen Square, and tossed it into a burning army truck.

Zhang said he thought that by destroying the videotape, he might save someone from jail or possibly death.

“They called us thugs and said we were against the government,” Zhang said, speaking in a whisper at times so other cafe patrons would not hear him. “We weren’t anti-government. But we were against what they were doing, their methods. Why were they using the army to crush their own people?”

Hundreds, possibly thousands, of people are believed to have been killed when troops stormed into the center of Beijing on orders from top party leaders to break up the pro-democracy protests.

Zhang said he and others rounded up after June 4 are “history’s sacrificial lambs.”

“The students didn’t face any serious consequences. They went back to school and were dealt with there, with reeducation classes,” he said. “But we were punished for the students to see ... because the government needed to restore social order.”

Sun Liyong (孫立勇), a former Beijing police officer, was arrested in 1990 for criticizing the government’s Tiananmen response. He spent seven years in prison with Zhang and about 150 other so-called “June 4 thugs,” and recorded his experiences in an unpublished memoir titled Crossing Ice Mountain.

An excerpt shared by e-mail describes how he spent 183 days in solitary confinement, his hands and feet shackled and linked by a chain, only able to eat like a dog, with his face in the plate.

Now living in Sydney, Australia, where he works for a moving company, Sun has established a fund for former Tiananmen prisoners. He sends US$450 to them when they first get out and more when he is able. He has also compiled case files for dozens of them, documenting their financial and health problems.

One of them describes how Sun Chuanheng (孫傳恆), released in 2006 after serving 18 years for setting two military trucks on fire, tried unsuccessfully to work as a newspaper delivery man and a door to door salesman.

Now he scrapes by earning US$88 a month at a friend’s hardware store, eating one meal a day. He could not be interviewed due to the terms of his parole.

Neither could Zhang Maosheng (張茂盛), who served 18 years for burning an army truck. He told Sun Liyong that he sometimes goes to a soup kitchen and has been so ashamed of his life outside that he wished he were back in prison.

Most of the former prisoners need medical attention for eye problems, high blood pressure, back trouble and other ailments but they can’t afford it, Sun said.

China’s Ministry of Justice did not immediately respond to faxed questions about the Tiananmen prisoners.

Last June, the US State Department said there were still an estimated 50 to 200 Tiananmen prisoners serving time in Chinese jails, and urged China to release them all.

China has not been a top-tier issue for much of the second Trump administration. Instead, Trump has focused considerable energy on Ukraine, Israel, Iran, and defending America’s borders. At home, Trump has been busy passing an overhaul to America’s tax system, deporting unlawful immigrants, and targeting his political enemies. More recently, he has been consumed by the fallout of a political scandal involving his past relationship with a disgraced sex offender. When the administration has focused on China, there has not been a consistent throughline in its approach or its public statements. This lack of overarching narrative likely reflects a combination

Behind the gloating, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) must be letting out a big sigh of relief. Its powerful party machine saved the day, but it took that much effort just to survive a challenge mounted by a humble group of active citizens, and in areas where the KMT is historically strong. On the other hand, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) must now realize how toxic a brand it has become to many voters. The campaigners’ amateurism is what made them feel valid and authentic, but when the DPP belatedly inserted itself into the campaign, it did more harm than good. The

For nearly eight decades, Taiwan has provided a home for, and shielded and nurtured, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). After losing the Chinese Civil War in 1949, the KMT fled to Taiwan, bringing with it hundreds of thousands of soldiers, along with people who would go on to become public servants and educators. The party settled and prospered in Taiwan, and it developed and governed the nation. Taiwan gave the party a second chance. It was Taiwanese who rebuilt order from the ruins of war, through their own sweat and tears. It was Taiwanese who joined forces with democratic activists

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) held a news conference to celebrate his party’s success in surviving Saturday’s mass recall vote, shortly after the final results were confirmed. While the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) would have much preferred a different result, it was not a defeat for the DPP in the same sense that it was a victory for the KMT: Only KMT legislators were facing recalls. That alone should have given Chu cause to reflect, acknowledge any fault, or perhaps even consider apologizing to his party and the nation. However, based on his speech, Chu showed