There’s not a red pen in sight when Russell Stannard marks his master’s students’ essays — but it’s not because the students never make mistakes. Stannard doesn’t use a pen, or even paper, to give his students feedback. Instead — and in keeping with his role as principal lecturer in multimedia and information and communication technology — he turns on his computer, records himself marking the work onscreen, then e-mails his students the video.

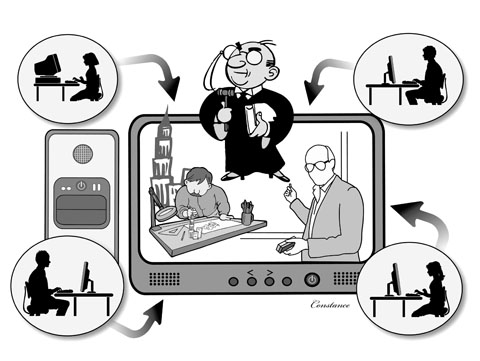

When students open the video, they can hear Stannard’s voice commentary as well as watch him going through the process of marking. The resulting feedback is more comprehensive than the more conventional notes scrawled in the margin, and Stannard, who works at the University of Westminster in London, now believes it has the potential to revolutionize distance learning.

“It started when I began to realize how useful technology can be for teaching,” he says. “I wanted to help other teachers, as well as general computer users, to learn how to use tools like podcasting, PowerPoint and BlackBoard, software that a lot of schools and universities use to allow teachers to provide course material and communicate with students online.”

So he set up a site to teach people how to use the technology, providing simple, video tutorials where users watch Stannard’s mouse pointing out how to use the software, with his voice providing constant commentary. He used the screen-videoing software Camtasia, and the site rapidly took off: It now receives more than 10,000 hits a month.

Then he started considering integrating the teaching style into his own university work.

“I was mainly teaching students on master’s courses in media and technology, and I realized that while I was talking about the benefits of new technology, I should be making the most of the opportunity to use it,” Stannard says. “That’s when I had the idea of video marking. It was immediately well received. Students receive both aural and visual feedback — and while we always talk about different learning styles, there are also benefits to receiving feedback in different ways.”

Stannard says the technology is particularly useful for dyslexic students, who appreciate the spoken commentary, and students learning English as a foreign language.

“I started my teaching career in language learning, so I quickly realized that students learning English would benefit from video marking. They can replay the videos as many times as they like and learn more about reasons for their mistakes,” he says.

Stannard also believes video marking is “perfect” for distance-learning students.

“It brings them much closer to the teacher,” he says. “They can listen, see and understand how the teacher is marking their piece, why specific comments have been made, and so on.”

The technology is already being used for informal distance learning, as Stannard uploads the videos he makes for his lectures at Westminster to multimedia trainingvideos.com. Now 60,000 people a month view the videos.

Online marking is part of a package of new technology that is transforming the face of distance education, from postal services-reliant correspondence courses to online, interactive learning. This is clearly evident on Second Life, the virtual world where users create personalized avatars to interact, which is home to scores of UK universities, with some teaching entire distance-learning modules through the site.

Kingston University in southwest London has developed a virtual courtroom for law students to practice on the site, while e-learning specialists at St George’s, University of London, have come up with a program code enabling Second Life users to create training scenarios.

One sees paramedic students enter Second Life to attend emergency scenarios. The characters have to assess and treat patients by speaking to them, checking their pulse, dressing wounds and administering drugs. They have to transport the patient into the ambulance and to the hospital, and then write handover notes, which are e-mailed to their real-life tutor for feedback.

While the technology is currently being used in-house at St George’s, the developers have made the code available for other universities or individuals. The code, Pivote, can be freely downloaded from Google Code, where techies can then use it to create virtual worlds to run other courses.

Terry Poulton, head of the Second Life-academia link-up at the university, says the code has potential applications beyond single disciplines.

“The technology could enhance any course with a focus on solving real-life problems, such as architecture, law, or engineering,” he says. “It could also be useful for professional development, particularly when preparing staff for crisis situations that they do not often face.”

Other academics are already using new technology to make university courses more accessible to working professionals. At Bournemouth University in southern England, a part-time master’s in creative media practice, launched in 2005, is run entirely online. Recruits are all working people who want to undertake further study but cannot commit to a face-to-face course. The students — more than a third of whom are international, living in South Africa, Mexico, New York and Finland — use blogs, podcasts and Skype to study. The first time the students and their tutors meet is normally at graduation.

Jon Wardle, associate dean of the media school at Bournemouth, says the course represents a changing mood in academia.

“Higher education has recognized the need to provide opportunities for lifelong learning for a long time, but the early work in the area was poor. Now, because of sites like YouTube, Facebook and Skype, these courses are really able to hit the spot and meet learner needs,” he says.

“Lecturers and students are both starting to understand that online learning doesn’t have to be a poor alternative to traditional campus-based courses. The days of the very bad, old-school correspondence courses are over. Now the future is about trying to discover new pedagogies which might not work face-to-face, but work wonderfully online,” he says.

Father’s Day, as celebrated around the world, has its roots in the early 20th century US. In 1910, the state of Washington marked the world’s first official Father’s Day. Later, in 1972, then-US president Richard Nixon signed a proclamation establishing the third Sunday of June as a national holiday honoring fathers. Many countries have since followed suit, adopting the same date. In Taiwan, the celebration takes a different form — both in timing and meaning. Taiwan’s Father’s Day falls on Aug. 8, a date chosen not for historical events, but for the beauty of language. In Mandarin, “eight eight” is pronounced

In a recent essay, “How Taiwan Lost Trump,” a former adviser to US President Donald Trump, Christian Whiton, accuses Taiwan of diplomatic incompetence — claiming Taipei failed to reach out to Trump, botched trade negotiations and mishandled its defense posture. Whiton’s narrative overlooks a fundamental truth: Taiwan was never in a position to “win” Trump’s favor in the first place. The playing field was asymmetrical from the outset, dominated by a transactional US president on one side and the looming threat of Chinese coercion on the other. From the outset of his second term, which began in January, Trump reaffirmed his

US President Donald Trump’s alleged request that Taiwanese President William Lai (賴清德) not stop in New York while traveling to three of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies, after his administration also rescheduled a visit to Washington by the minister of national defense, sets an unwise precedent and risks locking the US into a trajectory of either direct conflict with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) or capitulation to it over Taiwan. Taiwanese authorities have said that no plans to request a stopover in the US had been submitted to Washington, but Trump shared a direct call with Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平)

It is difficult to think of an issue that has monopolized political commentary as intensely as the recall movement and the autopsy of the July 26 failures. These commentaries have come from diverse sources within Taiwan and abroad, from local Taiwanese members of the public and academics, foreign academics resident in Taiwan, and overseas Taiwanese working in US universities. There is a lack of consensus that Taiwan’s democracy is either dying in ashes or has become a phoenix rising from the ashes, nurtured into existence by civic groups and rational voters. There are narratives of extreme polarization and an alarming