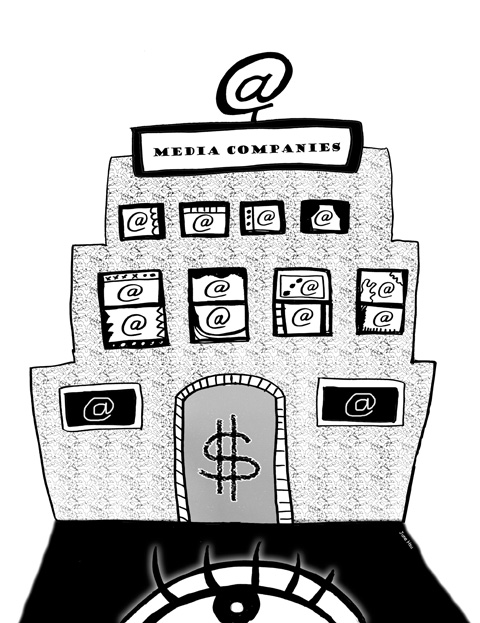

Just a year ago, most media companies believed the formula for Internet success was to offer free content, build an audience and rake in advertising dollars. Now, with the recession battering advertising online, in print and on television, media executives are contemplating a tougher trick: making the consumer pay.

Publishers like Hearst Newspapers, The New York Times Co and Time Inc are drawing up plans for possible Internet fees. Jeffrey Bewkes, Time Warner’s chief executive, is promoting a plan called “TV Everywhere” to offer consumers a vast array of television online, provided they are paying cable TV customers. And Rupert Murdoch, who once vowed to make the Wall Street Journal’s Web site free, is now an evangelist for charging readers.

“People reading news for free on the Web, that’s got to change,” Murdoch said last week at a cable industry conference in Washington.

The Associated Press said on Monday that it intended to police the use of news articles linked on countless Web sites, where many consumers read them free, to make sure the sites shared advertising revenue with those who created the material.

But from networks selling downloads of TV shows, to music companies trying to curb file-sharing, to struggling newspapers and magazines, the make-or-break question is this: How do you get consumers to pay for something they have grown used to getting free?

Some industries have pulled it off. Coca-Cola took tap water, filtered it and called it Dasani, and makes millions of dollars a year. People who used to ask why anyone would pay for television now subscribe to cable and TiVo. Airlines charge for luggage, meals, even pillows. And some music fans who have downloaded pirated songs are also patrons of iTunes.

All of these success stories offered the consumer something extra, even if it was just convenience.

“With bottled water, it’s a kind of snobbery and the perception of healthiness that they have marketed,” said Priya Raghubir, professor of marketing at the Stern School of Business at New York University. “With downloads, the benefit is that the paying services allow you to sample many songs free, and you know it’s legal, and the TV shows have no commercials.

“With newspapers and magazines, there have to be features you can’t get anywhere else, and maybe part of what you would pay for is the privilege of helping the business survive, but that is more of a difficult sell,” Priya said.

Major publishers say they have not yet decided how to proceed, but that some changes are coming soon.

“We’re looking, of course, at ways to extract payments from the consumers of our news — micro-payments, subscriptions, memberships, licensing, even voluntary donations,” Bill Keller, executive editor of the New York Times, said last week in a speech at Stanford University. “In the coming months, I fully expect that the NYT will begin laying down some bets based on our best forecasts of how the relationship between journalists and their audience will evolve.”

Only a few publishers have tried such a transition, with mixed results. The Los Angeles Times and the New York Times each tried charging for access to some content online, then dropped the requirement because it cost them audience and advertising revenue.

Most publications have moved in the other direction, trying to draw the biggest audience for advertisers by offering content free. The Associated Press’ new approach straddles the usual reliance on ads, and the new move to charge someone — though not the consumer — for the content.

By adding free features like e-mail alerts, blogs, discussion forums and video, news organizations are trying to persuade readers that they provide something more valuable than the aggregators and blogs that attract news readers online. In 2006, the Washington Post became the first newspaper to win an Emmy for its video.

Eric Johnson, a professor at Columbia Business School, said he had been amazed by media companies repeatedly adding free online services, like on-demand video.

“Before you add something to your site, you should say that if consumers really want it, that should be part of a package that you could charge for,” he said.

That is an alien concept to many media veterans, who grew up in world where news and other content on television and radio were free, and newspapers made far more money from advertisers than from readers.

Before the recession, media executives saw their future in online advertising, which was growing by between 25 percent and 35 percent annually. But last year, overall Internet ad spending rose 10.6 percent, and only 3.5 percent for television networks, according to a report by the Interactive Advertising Bureau and PricewaterhouseCoopers. The Newspaper Association of America says that for its industry, online ad revenue dropped 1.8 percent last year.

The free-versus-paid debate is a recurring one. At the birth of the Internet, many sites charged for content, but by the late 1990s the prevailing view was that market forces favored free content. A consumer tollbooth raises money, but it also constricts the audience and ad sales. Media companies decided it was not worth the trade-off.

In 1995, Encyclopaedia Britannica began selling online subscriptions and attracted 70,000 paying customers. But in 1999 it opened its doors, hoping to take advantage of the Internet advertising boom. Two years later, it reversed course again, and now charges US$70 a year to access most of its site.

When it resumed charging in 2001, it got back to 70,000 subscribers within 10 months, and now has about 200,000.

If the site hadn’t begun charging, “we would have a product that would be used by many more people today,” said Jorge Cauz, president of Encyclopedia Britannica, but it would probably generate less revenue.

The Journal began charging online in 1996, soon after its site was started, and before a mass audience could get accustomed to reading it free. Before taking over the paper 16 months ago, Murdoch said he wanted to make the site free, but with online subscriptions growing and ad sales soft, he decided to keep the pay wall.

The Web site of the Financial Times, FT.com, had more than 1 million registered users in 2001, when it began charging for access to much of its content though many articles remain open to anyone.

“After a year, we had 50,000 subscribers,” said Rob Grimshaw, managing director of FT.com.

Eight years later, the figure is up to 109,000, he said, a small portion of the number of readers who visit the site.

“You have to expect that at first, most of your customers won’t go along,” said Richard Honack, a professor at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University. “You have to train people — the academic word is ‘educate’ — to expect to pay, and unfortunately for media companies, they’ve trained people to expect the opposite.”

Getting customers to pay is easier if the product is somehow better — or perceived as being better — than what they had received free.

In adding a new feature, “you don’t want the starting value you place on it to be zero,” Johnson said. “People are very loss-averse, and the worst penny to pay is the first.”

Mark Mulligan, vice president of Forrester Research in London, said that even sectors that had successfully charged fees online, like the music industry, have found that it was a game of chasing niches. But products like sitcoms or general-interest newspapers have always been built for the broadest possible appeal.

“The question now is whether that common denominator approach can work online,” Honack said.

He says he thinks it will require treating the audience and the products as a series of niches and tailoring the offering to the customer.

“You have to find out what part of your product you can get them to come back for,” he said.

China has not been a top-tier issue for much of the second Trump administration. Instead, Trump has focused considerable energy on Ukraine, Israel, Iran, and defending America’s borders. At home, Trump has been busy passing an overhaul to America’s tax system, deporting unlawful immigrants, and targeting his political enemies. More recently, he has been consumed by the fallout of a political scandal involving his past relationship with a disgraced sex offender. When the administration has focused on China, there has not been a consistent throughline in its approach or its public statements. This lack of overarching narrative likely reflects a combination

Father’s Day, as celebrated around the world, has its roots in the early 20th century US. In 1910, the state of Washington marked the world’s first official Father’s Day. Later, in 1972, then-US president Richard Nixon signed a proclamation establishing the third Sunday of June as a national holiday honoring fathers. Many countries have since followed suit, adopting the same date. In Taiwan, the celebration takes a different form — both in timing and meaning. Taiwan’s Father’s Day falls on Aug. 8, a date chosen not for historical events, but for the beauty of language. In Mandarin, “eight eight” is pronounced

US President Donald Trump’s alleged request that Taiwanese President William Lai (賴清德) not stop in New York while traveling to three of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies, after his administration also rescheduled a visit to Washington by the minister of national defense, sets an unwise precedent and risks locking the US into a trajectory of either direct conflict with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) or capitulation to it over Taiwan. Taiwanese authorities have said that no plans to request a stopover in the US had been submitted to Washington, but Trump shared a direct call with Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平)

It is difficult to think of an issue that has monopolized political commentary as intensely as the recall movement and the autopsy of the July 26 failures. These commentaries have come from diverse sources within Taiwan and abroad, from local Taiwanese members of the public and academics, foreign academics resident in Taiwan, and overseas Taiwanese working in US universities. There is a lack of consensus that Taiwan’s democracy is either dying in ashes or has become a phoenix rising from the ashes, nurtured into existence by civic groups and rational voters. There are narratives of extreme polarization and an alarming