As a Tibetan living in China, even with a Chinese girlfriend, 28-year-old Abon feels trapped and claustrophobic, as every attempt to try and improve his life is blocked by the authorities.

He wants to travel to Europe, he says, to do business, but the Chinese government refuses him a permit to leave.

He wants to practise his Buddhist faith and follow the teachings of the monk he refers to as "my master," whose photograph he wears on a red string around his neck, but China does not allow Tibetans freedom of worship. Early this month, he wanted to go to Nepal and then India to visit his brother in Dharamshala, but his travel plans were curtailed by the military crackdown in his homeland which has closed the land borders.

He says he was accused of being an agent of the Dalai Lama after returning from a decade in India where he went as a teenager to live free of Chinese communist propaganda about his history and religion.

"I walked there alone when I was 12 and stayed in Mysore to get schooling and learn about my people and religion," he says, referring to the gruelling hike across the Himalayas that hundreds of thousands of Tibetans have made since the Dalai Lama was forced to flee into exile in 1959.

"I came back because I really missed my family," he said. "But it was a tough homecoming -- I didn't speak Mandarin until I came back and had to learn from scratch, and there was no work."

Now, having forgotten the English he learned in India and a fluent speaker of Chinese -- though he cannot read the language -- the stylish and personable Abon, who asked that his real name not be used, seems relaxed as he catches up with Tibetan friends at a huge entertainment complex in Chengdu shaped like a cruise ship.

Indeed, on the surface, Abon's life would seem light years from that of most people in China's Tibetan regions, where many are nomads on the grasslands, moving their families and livestock a few times a year.

China limits the number of Tibetans who enter monasteries, so many who wish to pursue religious studies cannot do so.

UNEMPLOYMENT

Unemployment is endemic among young and old alike, say Abon and other Tibetans, as most jobs go to Chinese immigrants to the region, who also receive stipends and tax breaks from central authorities for as long as they remain in the region.

Indisputably, most of China's Tibetans live in poverty, and complain they are marginalized from the subsidized economic development as much of the funding earmarked for the region, they say, is pocketed by corrupt officials.

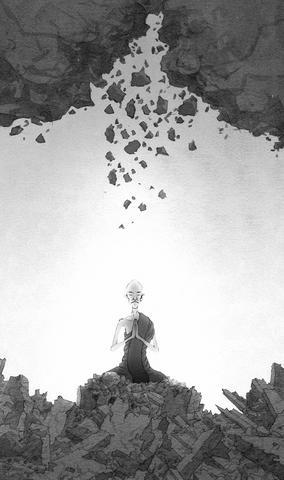

Poverty, repression and marginalization are seen as contributing to protests and riots that this month erupted across Tibetan regions.

Marches that began in Lhasa on March 10 to mark the anniversary of the failed uprising in 1959 against Chinese rule that led to the Dalai Lama's departure for India turned deadly on March 14.

Chinese authorities put the number of dead at around 18 -- "innocents" killed by rioters -- while the Dalai Lama and rights groups fear fatalities are much higher.

Abon, who was in Lhasa when the violence took hold, said he fears the number of dead could stretch into the hundreds or even thousands as Chinese security forces begin arrests and lockdown areas of the Tibetan capital.

"We know what the Chinese do to our people," he said after arriving in Chengdu, capital of Sichuan Province, half of which was part of Tibet before the Chinese invaded in 1950 and redrew Tibet's borders.

Half of what was Tibet now sits in Sichuan, Qinghai, Yunnan and Gansu provinces.

Referring to the imprisonment of Tibetans -- ordinary people as well as monks and nuns -- who express support for independence, Abon said he expected the crackdown to be brutal and long-lasting.

In contrast to most Tibetans, Abon lives in comparative comfort in Beijing with his Chinese girlfriend, a fervent Buddhist from a conservative and well-connected communist family who uses a Tibetan name.

The couple met in Chengdu two years ago while on vacation and have been together ever since, said the girlfriend, who asked not to be named.

They do not face any prejudice when out in public together in the capital, she said, though her family "do not approve" of the relationship.

"For two reasons -- one is that he is of an ethnic minority, and the other is social status," she said.

"My father is quite high ranking in the army, and he [Abon] is from an ordinary family. My mother, especially, has very strong feelings about my relationship and says it is not suitable," the girlfriend said.

But Abon's family, who live in a remote region of Sichuan, "just love me," she said.

"I don't speak Tibetan, but because I'm with him all the time, I can understand quite a bit. When I go to to see his family they speak in Sichuan dialect, and they really love me," she said.

VIOLENCE

In Lhasa with Abon for three weeks before they were forced to abandon their travel plans and return to Chengdu last week, she said once the protests turned violent she only felt safe in his company.

"If I'd been alone I would have been attacked, too. Chinese just weren't safe, but with him I was fine," she said.

Back on the grasslands of Sichuan, Abon's father and brothers grow Tibetan medicinal herbs during the summer.

"During the winter they work on the roads, or do other labouring jobs, because there is no other work," he said.

After returning from India, Abon said he spent a year with his family before moving to Beijing, where he worked in tourism and then became a trader, buying clothing in the capital to sell back home.

Now, he said, he sells the Tibetan medicine his father grows, but adds: "It's not a good living."

One of the few industries where Tibetans have enjoyed success in recent years is in selling traditional medicines to the rest of China.

"I want to go to France to expand my work and the French have no problems giving me a visa. But the Chinese government won't give me a permit to leave," he said.

"After I came back, they said I was an agent of the Dalai Lama, and refused to give me a passport. I waited three years, and still had to pay a bribe of 15,000 yuan [US$1,800]," he said. "They don't want people to go out and tell the world what it's like inside for Tibetans. They're holding the Olympics, so they need everything to look good on the surface."

"Things are very tough for Tibetan people. So the anger builds up," he said.

"Now that people are being rounded up, and locked in, you can only guess at what is happening to them. We know it is more than likely that they are being killed," he said.

"If life was OK, Tibetan people would have no need to demonstrate in the streets. But they have nothing to lose, their lives are hardly worth living. So they're not afraid to die. Life is that bad for most Tibetans," Abon said.

"The Chinese government say they are very good to Tibetans, that they give so much money. But the officials eat it. It never gets to the ordinary people," he said.

"Tibetans have nothing -- they're not even allowed to have their religion. You know, it's not even possible to say the Dalai Lama's name here. Tibetans are left out of everything," he said.

Congratulations to China’s working class — they have officially entered the “Livestock Feed 2.0” era. While others are still researching how to achieve healthy and balanced diets, China has already evolved to the point where it does not matter whether you are actually eating food, as long as you can swallow it. There is no need for cooking, chewing or making decisions — just tear open a package, add some hot water and in a short three minutes you have something that can keep you alive for at least another six hours. This is not science fiction — it is reality.

A foreign colleague of mine asked me recently, “What is a safe distance from potential People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Rocket Force’s (PLARF) Taiwan targets?” This article will answer this question and help people living in Taiwan have a deeper understanding of the threat. Why is it important to understand PLA/PLARF targeting strategy? According to RAND analysis, the PLA’s “systems destruction warfare” focuses on crippling an adversary’s operational system by targeting its networks, especially leadership, command and control (C2) nodes, sensors, and information hubs. Admiral Samuel Paparo, commander of US Indo-Pacific Command, noted in his 15 May 2025 Sedona Forum keynote speech that, as

In a world increasingly defined by unpredictability, two actors stand out as islands of stability: Europe and Taiwan. One, a sprawling union of democracies, but under immense pressure, grappling with a geopolitical reality it was not originally designed for. The other, a vibrant, resilient democracy thriving as a technological global leader, but living under a growing existential threat. In response to rising uncertainties, they are both seeking resilience and learning to better position themselves. It is now time they recognize each other not just as partners of convenience, but as strategic and indispensable lifelines. The US, long seen as the anchor

Kinmen County’s political geography is provocative in and of itself. A pair of islets running up abreast the Chinese mainland, just 20 minutes by ferry from the Chinese city of Xiamen, Kinmen remains under the Taiwanese government’s control, after China’s failed invasion attempt in 1949. The provocative nature of Kinmen’s existence, along with the Matsu Islands off the coast of China’s Fuzhou City, has led to no shortage of outrageous takes and analyses in foreign media either fearmongering of a Chinese invasion or using these accidents of history to somehow understand Taiwan. Every few months a foreign reporter goes to