After the sack of Nanjing in 1841, then imperial capital of China, the British secured what the Chinese still call the unequal treaty; Britain won control of Hong Kong and the right to trade freely in opium; the Chinese got nothing. And it was at Nanjing in 1937 that the Chinese were again and more bloodily humiliated by foreigners.

The Japanese murdered an estimated 300,000 civilians and soldiers in an atrocity whose calculated, indifferent cruelty rivalled a Nazi death camp, but to which the world has been curiously indifferent.

Yet today this once decaying symbol of China's century-long weakness is at one end of a booming 320km long corridor of factories and worker flats; at the other end sits the throbbing mega-sprawl of Shanghai.

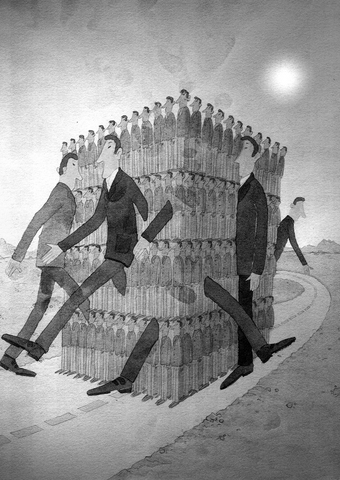

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

China is beginning to meet the economic expectation that it has long promised but never delivered, due to a phenomenon that dare not openly speak its name. Capitalism, a distinctive and more socially minded Chinese capitalism but capitalism none the less, is irreversibly taking root in the world's most populous, and communist, country. Nothing is likely to be the same again. Nanjing's ambitions, and its capacity to meet them, is tribute to that. As the deputy director of the city's economic commission explained to me, it aims to become China's No. 1 knowledge city. It has 37 universities.

A state-of-the-art metro system with bullet trains begins operation this autumn. The plan is to combine this extraordinary infrastructure with the opportunities of globalization to make the city's three core industries -- automobiles, petrochemicals, and information and communication technoloy (ICT) -- super-competitive.

I asked him and a group of businessmen he had arranged for me to meet if there was any going back. None, they nodded in unison. Nobody in China had any other prospectus than more of what was so evidently working.

Openness to inward investment is galvanizing Nanjing's industrial base. Ford and Fiat have given the local car and truck industry, and its supply chain, critical mass and international quality standards.

The latest addition is Rover, for Nanjing is where Rover's new manufacturing capacity is to be located after its Chinese takeover.

The plan is that Rover's research capacity and high value-added production in the UK are to be maintained while volume car production takes off in the Nanjing-Shanghai corridor, taking advantage of new access to the European market.

The Rover bet may even come off. Part of the current economic alchemy is that Chinese wage costs are up to a 30th of those in the West for workers whose skill levels and productivity, with the same equipment, are equal to their Western counterparts. Every worker who leaves the land for the factory thus contributes to the boom. The other part is rising demand, fueled by increasingly affluent Chinese consumers in their hundreds of millions, together with a protracted Keynesian stimulus on infrastructure spending on an unparalleled scale. The resulting growth, if it continues, will turn China into the world's second biggest economy within 20 years.

The change-makers on the ground are an increasingly confident Chinese private business sector and a tidal wave of foreign inward investment, all aware that this is the 21st-century Klondike. Even some of the wholly nationalized, inefficient, state-owned enterprises burdened by having to provide cheap houses and pensions for every worker are getting in on the act.

But maintaining the pace of growth is not guaranteed, a potential disaster for an economy that needs to find 10 million new jobs a year to hold off massive social unrest. Hudong-Zhonghua is the exception rather than the rule. Most managers of Chinese state-owned enterprise are communist administrators with no idea about business practice.

Paying interest on bank loans, for example, is an alien concept; if the big four Chinese banks, despite massive infusions of capital, ever had to accept the resulting loan write-offs, they would go broke. But it's a contagion that affects the private sector. Half the shares quoted on the Shanghai stock market have never paid a dividend. Too many Chinese businessmen think that money comes free; if the attitude doesn't change, ultimately the money tap will have to shut, bringing the growth engine to a halt.

It is issues like these that are now preoccupying the party leadership, as this month's annual party conference showed. The first phase of China's growth -- opening up to globalization, permitting a limited degree of market freedoms and launching a wave of massive infrastructure spending -- has been the easiest.

The "soft" infrastructure of a market economy -- accounting practice, credit appraisal, allocating resources to companies that need it, trustworthy and predictable law, professional, uncorrupt business ethics, worker representation and voice, free information flows and a critical media -- has to be both permitted and then developed to sustain growth. Businesses, for example, have to pay interest on their loans and dividends on their shares and to be held to account if they do not.

Last week marked a turning point; the leadership openly recognized that addressing these issues was to define the next phase of Chinese development, along with a redoubling of efforts to lower the stunning disparities in wealth between the booming east coast and the desperately poor west. But the prerequisite is to maintain the growth momentum and that, in turn, is now dependent upon a robust soft infrastructure. Which, in turn, means completing the transition not just to the form of capitalism but to its content.

The Communist Party doesn't call it that; it prefers "harmonious economic development" or the "socialist market economy." But this is capitalism by any other name. It is certainly not red-blooded, hire-and-fire American capitalism, nor ever will be. "Confucian" capitalism will join European capitalism as another economic and social model with which to challenge the US variant.

But it will be impossible to develop a soft economic infrastructure without political ramifications; a soft political infrastructure that embodies more transparency, pluralism and accountability is part of the same process.

In short, a form of democracy is on the agenda; the question is not if but how and what. It will have to respect China's particularities. There is acute awareness about how easy it is for a country of 1.3 billion people to split, but it must happen none the less. The genie is out of the bottle and the future of the world hangs on the outcome.

As the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its People’s Liberation Army (PLA) reach the point of confidence that they can start and win a war to destroy the democratic culture on Taiwan, any future decision to do so may likely be directly affected by the CCP’s ability to promote wars on the Korean Peninsula, in Europe, or, as most recently, on the Indian subcontinent. It stands to reason that the Trump Administration’s success early on May 10 to convince India and Pakistan to deescalate their four-day conventional military conflict, assessed to be close to a nuclear weapons exchange, also served to

The recent aerial clash between Pakistan and India offers a glimpse of how China is narrowing the gap in military airpower with the US. It is a warning not just for Washington, but for Taipei, too. Claims from both sides remain contested, but a broader picture is emerging among experts who track China’s air force and fighter jet development: Beijing’s defense systems are growing increasingly credible. Pakistan said its deployment of Chinese-manufactured J-10C fighters downed multiple Indian aircraft, although New Delhi denies this. There are caveats: Even if Islamabad’s claims are accurate, Beijing’s equipment does not offer a direct comparison

After India’s punitive precision strikes targeting what New Delhi called nine terrorist sites inside Pakistan, reactions poured in from governments around the world. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) issued a statement on May 10, opposing terrorism and expressing concern about the growing tensions between India and Pakistan. The statement noticeably expressed support for the Indian government’s right to maintain its national security and act against terrorists. The ministry said that it “works closely with democratic partners worldwide in staunch opposition to international terrorism” and expressed “firm support for all legitimate and necessary actions taken by the government of India

Minister of National Defense Wellington Koo (顧立雄) has said that the armed forces must reach a high level of combat readiness by 2027. That date was not simply picked out of a hat. It has been bandied around since 2021, and was mentioned most recently by US Senator John Cornyn during a question to US Secretary of State Marco Rubio at a US Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing on Tuesday. It first surfaced during a hearing in the US in 2021, when then-US Navy admiral Philip Davidson, who was head of the US Indo-Pacific Command, said: “The threat [of military