Achieving a free-trade pact with the US was supposed to be the magic moment that certified Chile's entry into the elite club of stable, democratic and prosperous nations. Instead, the new accord, signed in January, has reignited a sometimes anguished debate here about what it means to be Latin American and whether Chile has lost those essential characteristics.

Since the beginning of the decade, all three of Chile's neighbors have suffered political and economic convulsions that have forced changes of government. In sharp contrast to Argentina, Bolivia and Peru, not to mention the rest of South America, Chile these days looks "dull but virtuous," to borrow the title of a recent report by one Wall Street brokerage house.

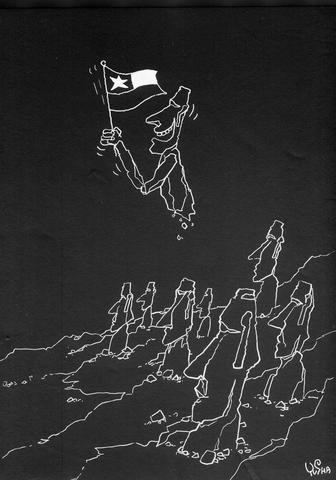

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

This is a country where most people actually pay their taxes, laws are rigidly enforced and the police only rarely seek bribes. That is unusual for Latin America and probably should be cause for celebration. Yet, it has the rest of the region looking at Chile as if there is something wrong with it because it is not what the Brazilians call "bagunca" or what the Argentines call "quilombo" -- passionately messy, turbulent and chaotic.

"The image of Chile for many years has been that of a country that is `different' and solitary," the Peruvian political commentator Alvaro Vargas Llosa, wrote in a recent essay that generated much comment here.

"Curiously, although Chile has undertaken a growing trade with the world and attracted investments, it was perceived as `isolated' in a space that is psychological more than political or economic," Vargas Llosa wrote.

Chileans were reminded of their unpopularity late last year, when an uprising in neighboring Bolivia overthrew a president who favored exporting natural gas through a Chilean port. Bolivia has been landlocked since losing a war to Chile in 1879, and Chileans were shocked to discover that many Latin Americans -- led by the Venezuelan president, Hugo Chavez -- supported Bolivia's historical claim to recover a piece of its coastline.

It has been this way for at least a generation, Chile as South America's odd man out. When Salvador Allende came to power in 1970, the rest of the Southern Cone was ruled by right-wing military dictatorships, and by the time those countries began to swing back toward democracy in the 1980s, General Augusto Pinochet was in power.

Chileans gained sympathy during the Pinochet dictatorship, when "solidarity with Chile was a cause that people in Latin America believed in, somewhat like Spain was in the late 1930s," said the writer Ariel Dorfman. But that changed when democracy returned, he said.

"Many people resented how Chileans, especially our entrepreneurs, behaved, buying up all the banks and telephone and electricity companies and acting arrogant and obnoxious," Dorfman said.

Today, Chile is a hypercapitalist state at a time when Argentina, Venezuela, Ecuador, Brazil and Uruguay are all moving leftward and questioning free trade and open markets. Chile may also be suffering from what might be called teacher's pet syndrome. Since the 1980s, other Latin American countries have had to endure repeated lectures from the US, Europe and Japan on the need to become more like Chile in opening their economies to the world and combating corruption.

"For some mysterious socio-cultural reason, we have been 'the serious kids in the neighborhood,'" Mario Waissbluth, a business consultant here, acknowledged recently in an essay for the newspaper La Tercera. "We are the nerd student who does all of his homework and is loathsome to the rest" of his classmates.

"Obviously it's better to be dull and virtuous than bloody and Pinochetista, but Chile has been a very gray country for many years now," said Dorfman, whose novel The Nanny and the Iceberg deconstructs Chile's "cool and efficient" image of itself. "Modernization doesn't necessarily have to come with soullessness, and I think there is a degree of that happening," Dorfman said.

The Free-Trade Agreement with the US has aggravated all these contradictory sentiments.

"Everyone, from Peru to Colombia, is fighting tooth and nail to get the same status," Vargas Llosa wrote. "But it pains them that Chile has got there ahead of them."

Government officials here say they are conscious of their spotty image and are moving to mend fences with their neighbors. But their initiatives have been limited mainly to trade-oriented efforts like dispatching delegations to Brazil and Central America to advise on what to expect in negotiations with the US.

"My concern is that of Chileans being seen as the new Phoenicians of Latin America, just good at trade," said Maria de los Angeles Fernandez, a political scientist at Diego Portales University here. "That is not sufficient to have good relations. You need other means of communication."

Simultaneously, though, Chile is also looking to establish alliances beyond its own troubled neighborhood. A free-trade agreement with the EU went into effect last year, a similar accord with South Korea has been ratified and in November Chile will play host to a conference of the 21-member APEC conference -- an effort to strengthen its identity as part of the equally dull but virtuous Pacific basin.

"We are trying to do everything within our reach to integrate ourselves" with the world beyond Latin America, Ricardo Lagos Weber, the main organizer of the conference and the son of the president, acknowledged in an interview.

But there is also a recognition here, he added, that Chile "can't be an enclave of modernity surrounded by poverty, instability and bad vibes" without suffering any of the consequences.

As the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its People’s Liberation Army (PLA) reach the point of confidence that they can start and win a war to destroy the democratic culture on Taiwan, any future decision to do so may likely be directly affected by the CCP’s ability to promote wars on the Korean Peninsula, in Europe, or, as most recently, on the Indian subcontinent. It stands to reason that the Trump Administration’s success early on May 10 to convince India and Pakistan to deescalate their four-day conventional military conflict, assessed to be close to a nuclear weapons exchange, also served to

The recent aerial clash between Pakistan and India offers a glimpse of how China is narrowing the gap in military airpower with the US. It is a warning not just for Washington, but for Taipei, too. Claims from both sides remain contested, but a broader picture is emerging among experts who track China’s air force and fighter jet development: Beijing’s defense systems are growing increasingly credible. Pakistan said its deployment of Chinese-manufactured J-10C fighters downed multiple Indian aircraft, although New Delhi denies this. There are caveats: Even if Islamabad’s claims are accurate, Beijing’s equipment does not offer a direct comparison

After India’s punitive precision strikes targeting what New Delhi called nine terrorist sites inside Pakistan, reactions poured in from governments around the world. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) issued a statement on May 10, opposing terrorism and expressing concern about the growing tensions between India and Pakistan. The statement noticeably expressed support for the Indian government’s right to maintain its national security and act against terrorists. The ministry said that it “works closely with democratic partners worldwide in staunch opposition to international terrorism” and expressed “firm support for all legitimate and necessary actions taken by the government of India

Minister of National Defense Wellington Koo (顧立雄) has said that the armed forces must reach a high level of combat readiness by 2027. That date was not simply picked out of a hat. It has been bandied around since 2021, and was mentioned most recently by US Senator John Cornyn during a question to US Secretary of State Marco Rubio at a US Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing on Tuesday. It first surfaced during a hearing in the US in 2021, when then-US Navy admiral Philip Davidson, who was head of the US Indo-Pacific Command, said: “The threat [of military