A North American ad for the satellite station al-Jazeera features a picture of a small child looking wistfully up at a satellite dish.

"The dish speaks Arabic," says the ad copy in Arabic. "Does your child?"

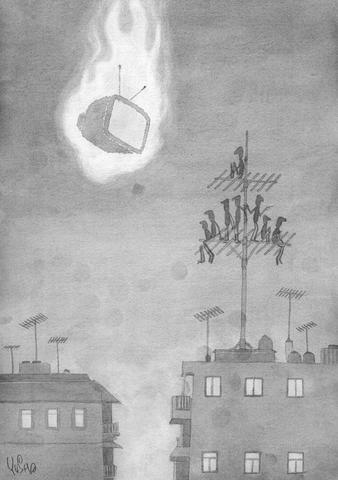

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

The commercial is designed to tug the heartstrings -- and purse-strings -- of the Arab diaspora in London, Boston or Buenos Aires.

This is al-Jazeera, phase II. The Arabic satellite channel, based in Doha, Qatar, burst on to the Western consciousness in the immediate aftermath of the Sept. 11 attacks. When Osama bin Laden chose to call the faithful to jihad or to condemn the Great Satan, Al Jazeera was the medium he used. He understood, as Western governments and broadcasters quickly came to realize, that it was the quickest way to reach the largest number of Arab speakers in the world.

Then came Iraq, and this time US President George W. Bush and British Prime Minister Tony Blair were ready for Al Jazeera. Sure enough, many of the war's controversies, from the close ups of the bodies of two British soldiers to the bombing of the Hotel Palestine, revolved around the station. But with the station's owner, the Emir of Qatar, asking the channel to become more independent, it is having to prove it is more than a talking point.

It has been said by several commentators that al-Jazeera is the new CNN. With more than 35 million regular viewers in 22 Arab countries and some 10 million subscribers outside, it has one of the world's largest audience bases. But for a number of reasons peculiar to the Arab world translating global reach into commercial success is not so easy.

Al-Jazeera was launched in the mid-1990s out of the ashes of the BBC World Service's Arab TV service by the Emir of Qatar. The Emir, who regards al-Jazeera with great pride, has shelled out as much as US$150 million a year to fund the station. But last year he told his favorite child it was time it started to support itself. For this reason, the station is now trying to diversify outside of the Arab world, with a raft of new channels, including a documentary channel, an English-language channel and English-language Web sites.

On the face of it, it should be an easy sell. The disillusionment among Asian audiences in Britain with national broadcasting is well documented. The BBC was sufficiently moved by the drift of ethnic minority audiences -- particularly Asian ones -- away from its radio and TV channels to refer to the trend in its annual report. A study of viewing patterns among Asians found a "deep lack of trust" of the main broadcasters' coverage of issues affecting Islam and relations between the Middle East and the West. And indeed, British Asians have taken to al-Jazeera in a big way -- some 87 percent have access to the channel via Sky.

But converting viewers to revenue isn't a walk in the park. Al-Jazeera's biggest source of earned revenue, and the one it wants to grow, is advertising. But its controversial stance has hit revenues at home in the Middle East. If US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld thinks al-Jazeera is provocative, they should try spending a few weeks in the Gulf States.

Arab governments in the region dislike the station so much they regularly claim it is funded by the CIA and Mossad, and many global brands, in sympathy with local sensitivities, won't place advertising on it.

It's nearly impossible to get hard financial data out of al-Jazeera but official spokesman Jihad Ali Ballout admits ad revenue is increasingly threatened by the channel's editorial stance.

"Big advertisers who are closely allied to big business and the rulers of the Arab world are unwilling to advertise with al-Jazeera," he says.

"We have been under a de facto embargo in the Arab world, which has hit our advertising revenue substantially," he says.

Al-Jazeera's financial situation is a peculiarly Arabic Catch 22: the better it is editorially, the harder its coffers are hit. In the West, established traditions of freedom of speech have tended to take the edge off the most heavy-handed bullying by advertisers. The Arab world does not have the same indulgence.

"The big problem, financially, is that al-Jazeera alienates everyone in the Arab World because it criticizes Arab countries," says one senior al-Jazeera source. "Ad agencies are always being told `We won't do business with you if you advertise on al-Jazeera.' There's tended to be a culture that if something offends you, you just pull all the ads."

This is one reason why the expansion into English language services is so important. It doesn't just add new subscribers, it allows al-Jazeera to broaden its "footprint," making it a channel global brands can ill afford to ignore.

It also offers massive potential for subscription revenue. Most Muslims don't speak Arabic. Think Pakistan with its population of 140 million and Indonesia with 200 million, the most populous Muslim country in the world.

With around 4 million European subscribers, about 1 million in the US and handfuls in South America and the Far East, there is clearly a rich vein still to be mined. Footage sales are another promising avenue of expansion. "During times of crises we have a position of unprecedented access to the Arab world which is invaluable for western broadcasters," Ballout says. "This is something we want to capitalize on."

Al-Jazeera is now toughening up its stance and cracking down when rivals rip off its coverage, as they did in Afghanistan after realizing what great access the channel had.

But even this isn't, yet, as lucrative as you might think. Al-Jazeera lacks the global infrastructure and state-of-the-art archive facilities of a Reuters or an Associated Press, so sales tend to be ad hoc pictures bought on the day rather than longer-term deals. Even the much-trumpeted deal with the BBC to share facilities and footage during the Iraq invasion is thought to have netted the broadcaster little more than a few hundred thousand dollars.

For these reasons many insiders doubt whether the Emir will be able, in the short term, to make good his promise to cut the funding.

For these reasons many insiders doubt whether the Emir will be able, in the short term, to make good his promise to cut the funding.

"The Emir has withdrawn his funding in the sense that I say to my college-age children `get a job,'" says one insider. "If you look at Qatar, you'll see why. Qatar is like Somerset with oil. Put yourself in the Emir's place. Al-Jazeera is a good thing. It's sexy and it's got prestige. It's arguably Qatar's most famous export. The Emir is very proud of it. Of course, he'd like it to be self-sufficient. But the bottom line is he's not going to stop funding it."

Al-Jazeera's cultural and status value far outweighs its financial clout. But for the time being, it will struggle to convert its relevance into revenue and may need to hang on to its parent's purse strings for some while.

Congratulations to China’s working class — they have officially entered the “Livestock Feed 2.0” era. While others are still researching how to achieve healthy and balanced diets, China has already evolved to the point where it does not matter whether you are actually eating food, as long as you can swallow it. There is no need for cooking, chewing or making decisions — just tear open a package, add some hot water and in a short three minutes you have something that can keep you alive for at least another six hours. This is not science fiction — it is reality.

In a world increasingly defined by unpredictability, two actors stand out as islands of stability: Europe and Taiwan. One, a sprawling union of democracies, but under immense pressure, grappling with a geopolitical reality it was not originally designed for. The other, a vibrant, resilient democracy thriving as a technological global leader, but living under a growing existential threat. In response to rising uncertainties, they are both seeking resilience and learning to better position themselves. It is now time they recognize each other not just as partners of convenience, but as strategic and indispensable lifelines. The US, long seen as the anchor

Kinmen County’s political geography is provocative in and of itself. A pair of islets running up abreast the Chinese mainland, just 20 minutes by ferry from the Chinese city of Xiamen, Kinmen remains under the Taiwanese government’s control, after China’s failed invasion attempt in 1949. The provocative nature of Kinmen’s existence, along with the Matsu Islands off the coast of China’s Fuzhou City, has led to no shortage of outrageous takes and analyses in foreign media either fearmongering of a Chinese invasion or using these accidents of history to somehow understand Taiwan. Every few months a foreign reporter goes to

The war between Israel and Iran offers far-reaching strategic lessons, not only for the Middle East, but also for East Asia, particularly Taiwan. As tensions rise across both regions, the behavior of global powers, especially the US under the US President Donald Trump, signals how alliances, deterrence and rapid military mobilization could shape the outcomes of future conflicts. For Taiwan, facing increasing pressure and aggression from China, these lessons are both urgent and actionable. One of the most notable features of the Israel-Iran war was the prompt and decisive intervention of the US. Although the Trump administration is often portrayed as