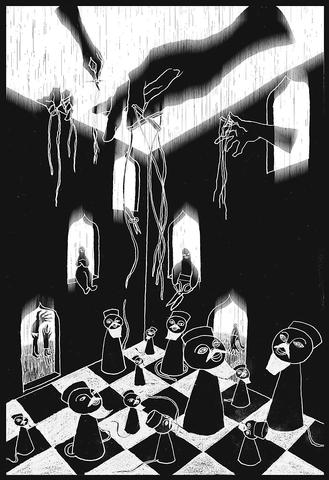

With the Taliban's rule disintegrating across Afghanistan, the US must now confront the "principal agent" problem that has been in the background since the war on terrorism began. Principal agents rely on proxies to carry out their plans. Getting someone else to do your dirty work always causes trouble. You cannot be sure that proxies will do what you tell them to do, and you may end up with your own hands as dirty as theirs.

In Afghanistan, the Uzbek and Tajik militias -- Hezbi Wahdat, Junbish, Jamyat Islami -- are the proxies the US has chosen to overthrow the Taliban. When last in Kabul, between 1992 and 1996, these militias fought each other and turned the city into the Dresden of the post-Cold War world. Knowing this, the Americans have tried over the first six weeks of the war to hold them back, bombing Taliban positions just enough so that they break apart, but not so hard that the Northern Alliance breaks through.

A bloodbath after a Northern Alliance victory would be like the revenge killings by Kosovars that followed the NATO victory in June 1999. In both cases, the principal agent, not the proxy, would take most of the blame. A bloodbath in Kabul or Mazar-i-Sharif (captured by the Northern Alliance) would be played out before a television audience of the entire Islamic world. If a war against terror is a battle for hearts and minds, it is hard to imagine anything that would do more harm to the principal agent's moral case.

ILLUSTRATION: MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

Controlling a proxy war from the air is not easy. Too much bombing and the proxy breaks through to commit mayhem. Too little bombing and the war stalemates. Just enough allows the Taliban to melt away or change sides. This is the balance America is trying to strike.

In addition to air-power, America's government hopes to control its proxies by means of the Special Forces and "advisors" working on the ground. Again, the balance the Americans have to strike here is delicate. Too many troops on the ground risks sucking America into the type of ground war that destroyed the Soviet empire. Too few exposes the principal agent to the risk of losing control of the proxy altogether. At the moment, there are hundreds, possibly thousands of Special Forces units on the ground, and they may be just sufficient to spot targets for the US Air Force and to act as a restraint on the essentially lawless troops of the Alliance.

Another consideration essential to fighting a proxy war is to prevent the proxy from appearing the stooge of the principal agent. The legitimacy of the proxies to their own people -- the Afghanis -- depends on their appearing to be independent of the Americans. The legitimacy of the principal agent also depends on not looking like an imperialist. So both sides have reasons to conspire in a war by remote control.

Proxy wars -- and the problems that accompany them -- are hardly new. America fought most of its wars against Communism through proxies. It funded Jonas Savimbi in Angola when it looked like he would be helpful in overthrowing the Marxist regime in the capital, Luanda. Unfortunately, all that the principal agent achieved was complicity in a devastating civil war. In Afghanistan, Osama bin Laden himself was a proxy in the jihad against the Soviets. In this case, victory was also followed by a devastating civil war. Proxies have a nasty way either of disgracing principal agents or turning against them.

Yet it is moral perfectionism to suppose that America can fight a war against terror without proxies. The only real alternative is to do all the fighting itself. This is what the enemy hopes for. Al-Qaeda must be hoping to lure long convoys of American soldiers and their equipment into those high, narrow mountain passes where the Russians were drawn in to their deaths. American strategy would be wise to deny Osama bin Laden that satisfaction.

So the principal agent uses proxies in order to avoid being sucked into a quagmire. But depending on proxies puts the principal agent's fate in the hands of people who may not define victory as the principal agent does: an Afghanistan rebuilt on solid political foundations and free of terror. For a warlord in American pay, victory might look like secure control of heroin production, together with death to his warlord rivals.

The real problems with proxy wars begin, paradoxically, once victory has been achieved. Revenge killings by militias, score-settling between militias, and battles over turf and resources could inflict still more agony on Afghanistan. A principal agent can win a war with proxies. A durable peace, however, cannot be built by remote control. Peace will require substantial commitment by the principal agents involved: peacekeeping troops, humanitarian assistance, rebuilding of infrastructure. No one in the international community has the stomach to actually disarm the proxies. But their leaders can be drawn into a political process and, with luck, be turned from warriors into politicians.

That will be the test of this war: whether a warrior culture can be turned into a political one, and whether proxies can gradually become principal agents in their own right, rebuilding a country they once devastated.

Michael Ignatieff is the Carr Professor of Human Rights Practice, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. Copyright: Project Syndicate

Congratulations to China’s working class — they have officially entered the “Livestock Feed 2.0” era. While others are still researching how to achieve healthy and balanced diets, China has already evolved to the point where it does not matter whether you are actually eating food, as long as you can swallow it. There is no need for cooking, chewing or making decisions — just tear open a package, add some hot water and in a short three minutes you have something that can keep you alive for at least another six hours. This is not science fiction — it is reality.

A foreign colleague of mine asked me recently, “What is a safe distance from potential People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Rocket Force’s (PLARF) Taiwan targets?” This article will answer this question and help people living in Taiwan have a deeper understanding of the threat. Why is it important to understand PLA/PLARF targeting strategy? According to RAND analysis, the PLA’s “systems destruction warfare” focuses on crippling an adversary’s operational system by targeting its networks, especially leadership, command and control (C2) nodes, sensors, and information hubs. Admiral Samuel Paparo, commander of US Indo-Pacific Command, noted in his 15 May 2025 Sedona Forum keynote speech that, as

In a world increasingly defined by unpredictability, two actors stand out as islands of stability: Europe and Taiwan. One, a sprawling union of democracies, but under immense pressure, grappling with a geopolitical reality it was not originally designed for. The other, a vibrant, resilient democracy thriving as a technological global leader, but living under a growing existential threat. In response to rising uncertainties, they are both seeking resilience and learning to better position themselves. It is now time they recognize each other not just as partners of convenience, but as strategic and indispensable lifelines. The US, long seen as the anchor

Kinmen County’s political geography is provocative in and of itself. A pair of islets running up abreast the Chinese mainland, just 20 minutes by ferry from the Chinese city of Xiamen, Kinmen remains under the Taiwanese government’s control, after China’s failed invasion attempt in 1949. The provocative nature of Kinmen’s existence, along with the Matsu Islands off the coast of China’s Fuzhou City, has led to no shortage of outrageous takes and analyses in foreign media either fearmongering of a Chinese invasion or using these accidents of history to somehow understand Taiwan. Every few months a foreign reporter goes to