The photo of his father was barely recognizable. The old man looked unusually pale and tired, and his customary beard was shaved off. The son who received the photo over WhatsApp was immediately suspicious.

He hadn’t heard from his family in western China for two years while he studied at a US university.

His family are Uighurs, a predominantly Muslim ethnic group that has become the target of a massive crackdown in China. Since 2017, more than 1 million people have been confined to internment camps and many more are monitored in their own homes.

Photo: AP

Why would he get this message now? And why would it come over WhatsApp? The messaging platform is censored for ordinary people in China, but often is used by authorities.

No words accompanied the photo, but he interpreted it as a kind of warning.

“I feel like I’m being watched even in the United States,” he said, speaking on condition of anonymity because he fears reprisals from the Chinese government. “They have all of our information. They know where we live.”

Photo: AP

SUSPICION AND SURVEILLANCE

Such fear of surveillance has become a fact of life for thousands of Uighurs living outside China and struggling to rebuild lives abroad, while family and friends go missing in China’s western Xinjiang region. Within China, the State Department says, many Uighurs have been subjected to torture and other abuse.

Even Uighurs who now live in the relative safety of the US, where their situation has sparked bipartisan concern in Congress, say they still fear being monitored and worry that speaking freely may spur reprisals against family members in Xinjiang.

“I hear these stories all the time,” said Kuzzat Altay, president of the Uighur American Association whose own father renounced him in a video released by Chinese authorities on social media. “People come to me crying.”

Altay, who came to the US as a refugee and has become a citizen, started a Uighur entrepreneurship network outside Washington. But most of the 25 members dropped out at the urging of family members in Xinjiang who had been visited by local authorities.

Altay said he thinks Chinese authorities worried that his entrepreneurship group would have discussed the crackdown back home.

The Chinese Embassy in Washington did not respond to a request for comment.

Ferkat Jawdat is a naturalized American citizen who came to the US nine years ago and works as a software engineer in Virginia. His mother was taken into the Xinjiang internment camps in 2018.

Last May, when she was briefly released, she called and told him not to speak out about Uighur issues. He later learned from relatives that she had contacted him at police insistence and was taken back into police custody the very next day.

The Chinese government is broadly suspicious of Uighurs who have spent significant time abroad, said Brian Mezger, an immigration lawyer who specializes in Uighur asylum cases.

“The Chinese government views exposure to foreign influence as basically polluting the Uighurs,” said Mezger, whose practice is based in Rockville, Maryland.

A dozen Uighurs interviewed in the US, most of whom did not want their names used, described various forms of intimidation.

They described calls from Chinese government officials instructing them to “check in” at Chinese consulates. Some were told their Chinese passports would not be renewed and were offered one-way travel documents back to China. Several said relatives back home were visited by local police looking for information about family members abroad.

The young man who received the photo of his father in June, two years after family members in Xinjiang warned him to cut off contact, says he doesn’t know what authorities wanted from him.

He also received a series of unsettling text messages in the Uighur language, but he responded in Chinese to ask why the sender had contacted him. The person sending the messages said that if he wanted to have a video chat with my father, he could arrange it.

“He wouldn’t say what he wanted from me.”

These accounts of harassment match reports compiled by activists and human rights groups, including Amnesty International, which last month documented widespread fear of surveillance and retribution among 400 Uighurs living in 22 countries.

PERSECUTED ETHNICITY

Uighurs qualify for asylum in the US because today they face almost certain detention if they return to China, said Mezger, who has represented hundreds of people from Xinjiang. He said nearly all of his cases have been successful.

The wait for asylum, however, can take years and the anxiety can be grueling.

“Even if you’re free in the US, you can’t leave the US while your asylum application is pending,” said James Millward, a professor of history who researches Xinjiang at Georgetown University.

Xinjiang, which means “new frontier” in Chinese, was brought under control of Chinese authorities in Beijing in the 19th century. But the western desert region has longstanding cultural, religious and linguistic ties to Central Asia and to Turkey.

Uighurs have faced numerous previous persecution and assimilation campaigns by the Chinese government.

An enhanced security state began to take shape in Xinjiang after 2009, when race riots left around 200 people dead in the capital city of Urumqi. In recent years, surveillance cameras and police checkpoints have become ubiquitous.

The government began to build internment camps in 2017 as a means of intimidation and social control. Former camp detainees have previously said that after being confined in the camps, they were forced to renounce their faith and swear fealty to China’s ruling Communist Party.

Uighurs face limits on the use of their language in schools, their ability to check into hotels and restrictions on cultural practices such as wearing beards and fasting during religious holidays.

The government’s goal is to “eradicate Uighur culture,” said Dolkun Isa, president of the World Uighur Congress.

He added that social controls have grown more stringent since the inception of Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s (習近平) Belt and Road Initiative — an overseas infrastructure funding policy — has enhanced the strategic importance of Xinjiang’s location bordering Central Asia.

China’s foreign ministry regularly bristles at international criticism of policies in Xinjiang, which it views as an internal matter.

It’s not possible to confirm that the intimidating messages received by Uighurs abroad come from Chinese officials. But the Uighurs’ accounts of harassment have been consistent enough that both Republicans and Democrats in Congress back legislation that would require the FBI to help protect Uighurs in the US.

The young man who received the photo of his father and the string of suspicious messages said he called the FBI and that two agents met with him. The agency wouldn’t comment on whether it investigated the particular case, but said in a statement: “Without discussing specifics, we take all reports of threats or intimidation seriously.”

Meanwhile, the man has continued his studies while he awaits a decision on his asylum application and worries about relatives in China. “They could punish my family, if they haven’t already sent them to the camps, because I didn’t cooperate.”

“Even if you have physical freedom, it’s very difficult to escape the reach of the Chinese government,” said Mezger, the attorney.

Next week, candidates will officially register to run for chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). By the end of Friday, we will know who has registered for the Oct. 18 election. The number of declared candidates has been fluctuating daily. Some candidates registering may be disqualified, so the final list may be in flux for weeks. The list of likely candidates ranges from deep blue to deeper blue to deepest blue, bordering on red (pro-Chinese Communist Party, CCP). Unless current Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) can be convinced to run for re-election, the party looks likely to shift towards more hardline

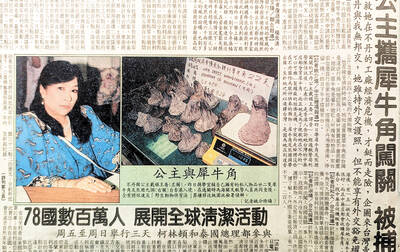

Sept. 15 to Sept. 21 A Bhutanese princess caught at Taoyuan Airport with 22 rhino horns — worth about NT$31 million today — might have been just another curious front-page story. But the Sept. 17, 1993 incident came at a sensitive moment. Taiwan, dubbed “Die-wan” by the British conservationist group Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), was under international fire for being a major hub for rhino horn. Just 10 days earlier, US secretary of the interior Bruce Babbitt had recommended sanctions against Taiwan for its “failure to end its participation in rhinoceros horn trade.” Even though Taiwan had restricted imports since 1985 and enacted

Enter the Dragon 13 will bring Taiwan’s first taste of Dirty Boxing Sunday at Taipei Gymnasium, one highlight of a mixed-rules card blending new formats with traditional MMA. The undercard starts at 10:30am, with the main card beginning at 4pm. Tickets are NT$1,200. Dirty Boxing is a US-born ruleset popularized by fighters Mike Perry and Jon Jones as an alternative to boxing. The format has gained traction overseas, with its inaugural championship streamed free to millions on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. Taiwan’s version allows punches and elbows with clinch striking, but bans kicks, knees and takedowns. The rules are stricter than the

Nearly three decades of archaeological finds in Gaza were hurriedly evacuated Thursday from a Gaza City building threatened by an Israeli strike, said an official in charge of the antiquities. “This was a high-risk operation, carried out in an extremely dangerous context for everyone involved — a real last-minute rescue,” said Olivier Poquillon, director of the French Biblical and Archaeological School of Jerusalem (EBAF), whose storehouse housed the relics. On Wednesday morning, Israeli authorities ordered EBAF — one of the oldest academic institutions in the region — to evacuate its archaeological storehouse located on the ground floor of a residential tower in