Oct. 21 to Oct. 27

While many Hong Kong residents desire to move to Taiwan in pursuit of freedom and democracy today, it wasn’t that great an idea three decades ago.

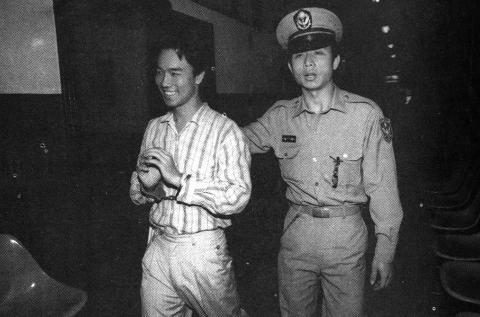

In January 1988, two days after arriving in Taiwan on business, Hong Kong citizen Chang Chi-lo (張驥犖) was arrested. Despite promising to immediately set him free, the authorities charged him with sedition and sentenced him to five years in prison on Oct. 26, 1988. Even though martial law had been lifted the previous year, the Punishment of Rebellion Act (懲治叛亂條例) enabling such procedures was still in effect.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Association for Human Rights

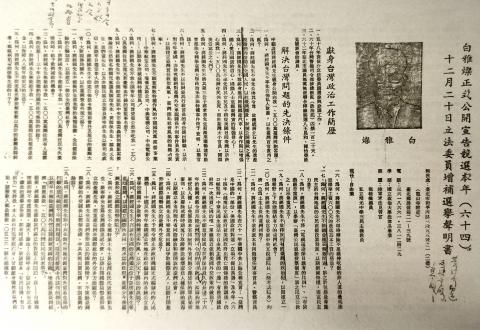

Thirteen years earlier in 1975, dissident politician Pai Ya-tsan (白雅燦) wrote: “The 15 million people of Taiwan have been living in a closed police state for 26 years. Our eyes have been covered, our ears plugged, our brain function suspended. The only freedom we have is to eat with our mouths and feel with our sexual organs. How different is that from the cows and pigs living in pens on ranches?”

Pai’s manifesto included a 29-point blistering critique of then-premier Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國), heir to the ruling Chiang dynasty. After distributing 10,000 copies on the street and mailing them to the press, government officials, opposition politicians and foreign embassies, Pai was arrested on Oct. 23, 1975 and sentenced to life in prison.

TWENTY-NINE QUESTIONS

Photo: Chang Tsung-chiu, Taipei Times

Pai was a long-time supporter of politicians who opposed the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), spending 120 days in jail in 1971 for his activities. In October 1975, while campaigning for a legislator, he discributed the offending flyers.

Pai’s critique directed 29 questions at Chiang, many of them blasting the premier’s extravagant lifestyle, nepotism and misuse of public funds. Pai asked Chiang to release his financial records, dissolve state-run enterprises, establish national health insurance and public housing and raise the minimum wage.

Politically, Pai demanded direct elections, the dissolution of the National Assembly, release of political prisoners, promotion of more Taiwan-born politicians and lifting of martial law, among others.

Photo courtesy of National Human Rights Museum

Pai’s manifesto detailed the hardships and oppression Taiwanese suffered under the authoritarian rule of the elite, who sought only to benefit themselves at the expense of the people. The “Taiwan Problem,” he wrote, stemmed from the rulers not being in tune with their constituents.

Another document expressed Pai’s political views: He vowed to donate his salary to help educate the poor, hoping that it would inspire the wealthy to follow suit. He hoped that the funds could also go toward building hospitals and taking care of the disadvantaged.

Every month, Pai and like-minded politicians held sessions critiquing Chiang and the government in front of landmarks such as Longshan Temple (龍山寺) and Taipei Confucius Temple (台北市孔廟). He promised to speak exclusively in Hoklo (also known as Taiwanese) during legislative sessions, and criticized the government’s restrictions on Hoklo television programming and traditional puppet shows.

Photo courtesy of Academia Historica

Government documents state that Pai became upset at the government after failing his college entrance exams, and was manipulated by other “traitors” into harboring seditious thoughts. They accused him of listening to communist broadcasts and claimed that he was “doing all he could to turn the population against each other, incite a rebellion and invite exiled independence activist Peng Ming-min (彭明敏) to return and head an opposition government.”

To the government, it was blasphemous to call for the dissolution of the National Assembly and insult the sacred task of defeating the communists and reclaiming the mainland.

Pai was charged with attempting to subvert the government, and sent to jail for life on Green Island (綠島). Chou Pin-wen (周彬文), who ran the shop that printed the flyers, was sentenced to five years.

Legislators and human rights groups continued to push for Pai’s release over the years, finally succeeding in April 1988 after the end of martial law. However, Chang’s detention that same year showed that the reign of White Terror had not yet gone away.

TRAPPED IN TAIWAN

A year after Pai’s arrest in 1975, Chang came to Taiwan to study electrical engineering at National Taiwan University. According to the Liberty Times (the Taipei Times’ sister newspaper), Chang’s ex-girlfriend reported him in 1983 for joining a leftist magazine and communist organization during high school, alleging that his studies in Taiwan were a front for his “subversive activities.”

Chang argued that he was just 15-years-old at the time and denied the charges, but he remained detained in Taipei. His pregnant wife visited him in prison a few times, and he missed the birth of his son.

Chang’s lawyer, future president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁), questioned the court for charging an individual for things he might have done when he was a teenager. Chang had visited Taiwan once after his ex-girlfriend reported him in 1983. Chen asked why he wasn’t arrested then, why there was no warrant and why he was allowed back in Taiwan in 1988 instead of being blacklisted.

On Oct. 26, 1988, Chang was sentenced to five years in prison. The magazine Taiwan Human Rights (台灣人權) questioned the decision, especially since Chinese citizens were soon to be allowed to visit relatives and attend funerals in Taiwan. “If they are members of the Chinese Communist Party, will they all be arrested on the spot as well?” the magazine wrote.

Chang appealed and his case dragged on for two more years, during which he was not allowed to leave Taiwan despite desperate pleas from his family in Hong Kong. Each time, the high court acquitted him, only for the prosecution to bring up the case again.

According to the Liberty Times, it had already been ascertained that the publication Chang had contributed to was not leftist, and that the organization he allegedly joined was only open to Chinese citizens, while Chang had a British passport.

Chang was finally allowed to go home in November 1990, ending the harrowing saga.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an