Nov. 26 to Dec. 2

The Tsou people called it Patungkuanu, which the Qing officials directly translated into Batongguan (八通關). The Japanese called it Niitakayama, or “New High Mountain,” after discovering that it was taller than Mount Fuji. And Westerners called it Mount Morrison, after the captain who sighted it when setting out from Anping (安平) in today’s Tainan.

Today, it’s known as Yushan, or Jade Mountain — and has been since Dec. 1, 1947. The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was quick to eradicate Taiwan of Japanese names after World War II, and Niitakayama reverted to its Qing Dynasty name.

Photo courtesy of National Taiwan Museum

The following passage is found in a Qing record from 1685, just two years after the empire annexed Taiwan: “When the weather is fair, it looks like a white stone from afar. That is why it is called Jade Mountain.”

HOLY MOUNTAIN

Jade Mountain was not the only name that appeared in Qing annals; there was also White Jade Mountain (白玉山) and Snow Mountain (雪山).

Photo courtesy of Fang Chin-chin

For most of the Qing Dynasty it was still uncharted Aboriginal territory, with an 1805 report describing the inhabitants as “savages that appear from nowhere, taking the heads of every person they see. Most people stay away from this area out of fear.”

By 1874, however, the Qing changed their policy of separating Aborigines and Han Chinese, and started building roads up the mountain.

Yushan has long been sacred to both Bunun and Tsou Aborigines. The mountain appears in many legends from both groups as a refuge to a great flood, which turned the peak into an island. In many versions, the waters receded after a crab defeated a giant snake or eel that was clogging up a major river. The Kanakanavu people have almost the same legend except it was a pig who defeated the snake/eel.

Photo courtesy of Yushan National Park Headquarters

The Tsou and Bunun also share tales of Yushan being the source of fire, which they sent a Taiwanese blue magpie to retrieve, giving the bird its reddish beak color. The species of the bird varies by story.

Li Yi-ching (李怡靜) writes in the study The Aborigine in the Legends of Yushan (玉山傳說中的原住民) that the main difference between the two peoples is that the Tsou believe they were created on the top of Yushan while the Bunun originated further to the west and only moved to Yushan after the flood.

Yushan remains a source of legends until this day. For example, many believe in a demon wearing a yellow raincoat that appears near Yushan’s south peak, giving hikers directions that will lead them off a cliff.

Photo: Chen Hsin-jen, Taipei Times

‘NEW HIGH MOUNTAIN’

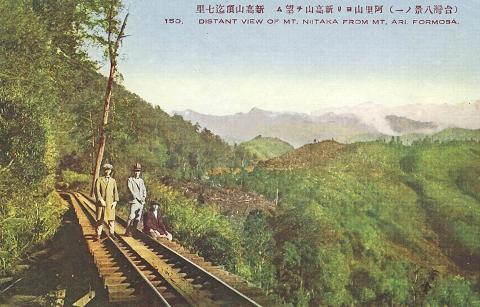

Even though the Qing didn’t cede Taiwan to the Japanese until 1895, Shiga Shigetaka’s Theory of Japanese Landscape, published in 1894, already included Taiwan and referred to the mountain as “Taiwan’s Fuji.”

According to the book Yushan History (玉山史話) by Lin Wen-chun (林玟君), it was such a huge deal for the Japanese to discover that Yushan was higher than Fuji, that the Meiji Emperor personally gave it the name Niitakayama on June 28, 1897. The official edict refers to the mountain’s previous name as “Mount Morrison.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

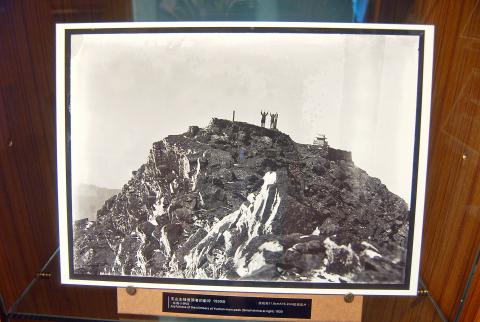

For the first few years of Japanese rule, there was much variation between the names of Yushan’s many peaks. The current designations of north, east, south, west and main peaks were standardized around 1904.

The exact height of Yushan also varied during the early Japanese era, ranging from 3,900 meters to 4,300 meters. Using new technology, the Japanese settled on 3,950 in 1925 — just two meters less than its official height today.

Niitaka became a popular name for places, ships, stores and businesses in Taiwan. Lin writes that when the Japanese government coded their orders for the bombing of Pearl Harbor as “Climb Niitakayama 1208,” with the number referring to the attack date (Japan time, as it was still Dec. 7 in Hawaii).

DECAPITATION ON MAIN PEAK

In the few years following Japanese defeat, the mountain was still referred to as “Xingaoshan,” the Mandarin pronunciation of Niitakayama, but eventually “Yushan” took over.

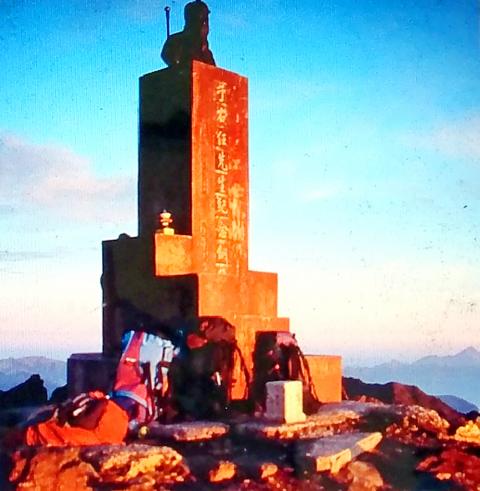

Instead of using Japanese measurements, Taiwanese officials went with the 3,997 meters surveyed by the US Army Forces Far East in 1957. This gave rise to the idea of building a 3-meter statue of the late Control Yuan President Yu You-ren (于右任) to reach 4,000 meters.

Before Yu died in 1964, he wrote a poem expressing his longing for his homeland of China: “Bury me on a high mountain so I can gaze toward my homeland; although I can never see it again, I will never forget it!”

The statue, facing west toward China, was unveiled in 1967 to a crowd of about 80 hikers chanting “Long Live President Chiang” (蔣介石).

As the KMT’s authoritarian rule waned in the 1980s, hikers began defacing the statue, sparking a debate on whether to keep or remove it. With the matter unresolved, a group cut off the statue’s head in 1995, but the park authorities retrieved and reattached it.

A year later, the entire statue was removed and thrown into a ravine, never to be found again. It was quickly replaced by the large stone which hikers pose with today.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Many people noticed the flood of pro-China propaganda across a number of venues in recent weeks that looks like a coordinated assault on US Taiwan policy. It does look like an effort intended to influence the US before the meeting between US President Donald Trump and Chinese dictator Xi Jinping (習近平) over the weekend. Jennifer Kavanagh’s piece in the New York Times in September appears to be the opening strike of the current campaign. She followed up last week in the Lowy Interpreter, blaming the US for causing the PRC to escalate in the Philippines and Taiwan, saying that as

US President Donald Trump may have hoped for an impromptu talk with his old friend Kim Jong-un during a recent trip to Asia, but analysts say the increasingly emboldened North Korean despot had few good reasons to join the photo-op. Trump sent repeated overtures to Kim during his barnstorming tour of Asia, saying he was “100 percent” open to a meeting and even bucking decades of US policy by conceding that North Korea was “sort of a nuclear power.” But Pyongyang kept mum on the invitation, instead firing off missiles and sending its foreign minister to Russia and Belarus, with whom it

When Taiwan was battered by storms this summer, the only crumb of comfort I could take was knowing that some advice I’d drafted several weeks earlier had been correct. Regarding the Southern Cross-Island Highway (南橫公路), a spectacular high-elevation route connecting Taiwan’s southwest with the country’s southeast, I’d written: “The precarious existence of this road cannot be overstated; those hoping to drive or ride all the way across should have a backup plan.” As this article was going to press, the middle section of the highway, between Meishankou (梅山口) in Kaohsiung and Siangyang (向陽) in Taitung County, was still closed to outsiders

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has a dystopian, radical and dangerous conception of itself. Few are aware of this very fundamental difference between how they view power and how the rest of the world does. Even those of us who have lived in China sometimes fall back into the trap of viewing it through the lens of the power relationships common throughout the rest of the world, instead of understanding the CCP as it conceives of itself. Broadly speaking, the concepts of the people, race, culture, civilization, nation, government and religion are separate, though often overlapping and intertwined. A government