July 23 to July 29

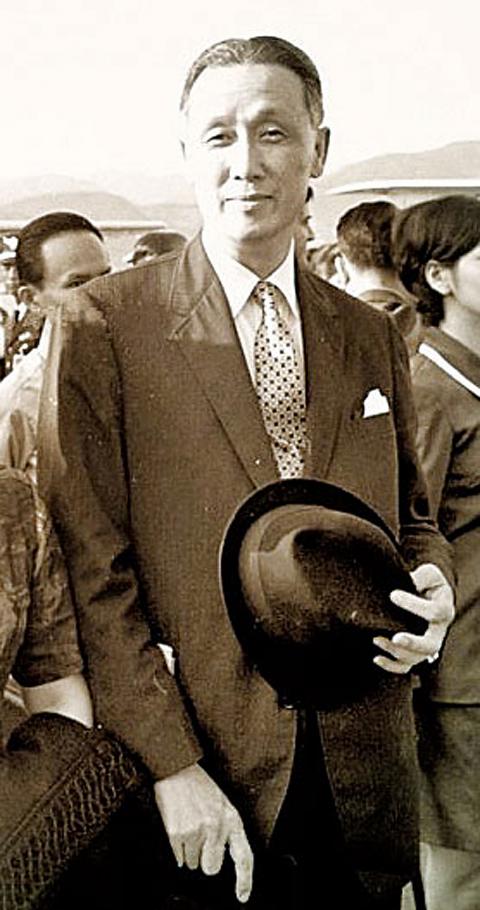

Koo Chen-fu (辜振甫) only discussed the incident once in public. It was May 1993, and firebrand Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) legislator Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) had been criticizing him publicly for months in a bid to try and stop the then-Straits Exchange Foundation (SEF, 海峽交流基金會) chairman from meeting his Chinese counterpart Wang Daohan (汪道涵) in Singapore.

After the conclusion of what would later be known as the historic Koo-Wang Talks, Chen continued to question Koo, finally bringing up the subject Koo had preferred to avoid: his sentencing in 1947 for his involvement in the “Plotting Taiwan Independence Incident” (謀議台灣獨立案), where he was accused of working with Japanese officers to create an independent Taiwan after Japanese surrender and before the arrival of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT).

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

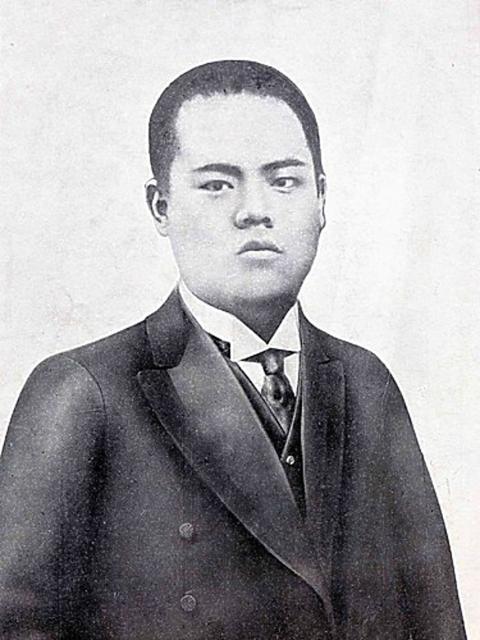

Chen’s camp had been trying to paint Koo, a long-time KMT member, as a traitor to the country, even calling out his late father, Koo Hsien-jung (辜顯榮), who invited Japanese troops into Taipei in 1895 after local resistance had crumbled and the city had descended into chaos. Some say he was being opportunistic, others say he did it to restore order and prevent further violence. Regardless, the family worked closely with the authorities and prospered under colonial rule.

Chen’s questioning about the 1946 incident finally rattled the usually stoic Koo.

“What’s so dishonorable about serving a groundless sentence? Is that betraying the country? It’s already unfair that the government never cleared my name. Today I have to suffer this treatment in the legislature. This is completely unjust!” he shouted.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

POST-WAR SENTIMENT

After Japan’s surrender on Aug. 15, 1945, the colonial Office of the Taiwan Governor-General reported that while most Taiwanese would likely accept Chinese rule, there were some who would worry about being treated as Japanese collaborators. Others were concerned about the KMT’s ability to rule properly. In response, the office instructed the police to focus on maintaining order, collecting information and to “decisively suppress all signs of scheming for Taiwanese independence.”

These feelings were not unusual. For example, Hsinchu assemblyman Huang Wei-sheng (黃維生) believed that he would have a better chance of surviving and preserving his property under an independent Taiwan approved by Japan, and made a petition to the local government. Yang Kui (楊逵), a novelist and anti-Japanese activist, also expressed his distaste for the KMT’s “reckless and brutal ways” in China, but the colonial reports note that “he was not of much influence.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Rikichi Ando, Japan’s final governor-general in Taiwan, reportedly told the independence petitioners that “I understand your sentiments for Taiwan independence. But looking at the bigger picture, for your sake, I suggest that you cease such activities. If you insist on proceeding, I will have no choice but to request the Japanese Army to suppress your movement.”

The sentiment faded quickly, however, as by September, colonial reports show that most of the population were preparing to welcome the arrival of the KMT. The Minpao (民報) newspaper ran an editorial in October of that year comparing independence activists to Qin Kuai (秦檜), a notorious figure in the Song Dynasty who is regarded as a traitor.

GUILTY OR NOT?

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The KMT arrested Koo and four other alleged independence petitioners in February 1946. On July 29, 1947, they were convicted of sedition. Koo received the longest sentence of over two years.

“Most people are overjoyed about the return of Taiwan to the motherland,” the verdict states. “But Koo Chen-fu and his accomplices leaned toward Japan, and were one of the few who lamented Japan’s loss.”

The verdict states that several Japanese officers who refused to accept surrender instigated the incident and recruited Taiwanese to join in their plan, which was only stopped after Ando made his warning.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“The so-called self-rule movement was started by the Japanese and would benefit the Japanese,” it continued. “This is essentially sedition under the guise of self-rule. We have sacrificed so much to fight the Japanese and liberate the people of Taiwan, yet these people are not only not grateful, but succumbed to Japanese influence.”

The reason for the relatively short sentences are revealed by the following: “Considering the fact that the Japanese are the instigators and the defendants have been brainwashed by the Japanese, their actions are somewhat forgivable.”

However, later interviews with former Japanese military officials in Taiwan show them insisting that they had nothing to do with the independence attempt.

Koo has long maintained his innocence, claiming that he actually tried to stop the attempt and the sentencing was punishment for the Koo family’s close ties to the colonial government. The son of Hsu Ping (徐丙), another defendant, also declared his father’s innocence. His version of events state that Hsu’s close associate Lin Hsiung-hsiang (林熊祥) angered then-governor general Chen Yi (陳儀) by demanding that he repay an overdue loan, and Chen arrested him and his friends as revenge.

Due to the lack of evidence, the truth is still unclear. However, Japanese records clearly state that Lin Maosei (林茂生) and other “Taiwanese elite” did make an attempt at independence right after Japanese surrender. Lin “disappeared” in the aftermath of the 228 Incident, leaving nothing behind that proves whether Koo and the other defendants were involved.

An interesting footnote to the story: While Koo Chen-fu became a KMT loyalist despite his alleged independence attempt, his half-brother Koo Kwang-ming (辜寬敏) is a DPP member and lifelong Taiwan independence activist.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them