The name Johnnie To (杜琪峯) is ubiquitous in Hong Kong cinema, but the prolific director and producer claims he might have never ended up making films, if it wasn’t for a stroke of luck 45 years ago.

As a then broke and unemployed 17-year-old, To joined Hong Kong’s leading television station TVB (Television Broadcasts Limited) on a whim, with no clue that it would eventually lead him to his true calling.

“I really just needed a job and some money. It wasn’t my choice, but I happened to be assigned to the drama department,” he says. “If I had been sent to the engineering department, I might have ultimately become an engineer.”

Photo courtesy of the Far East Film Festival

Today, the 63-year-old godfather of Hong Kong gangster films continues to be one of the most active and commercially successful filmmakers in the local industry, both in terms of quantity and quality. To has made more than 50 films since debuting in 1980, releasing at least two to three films a year without fail under his production company Milkyway Image (銀河映像).

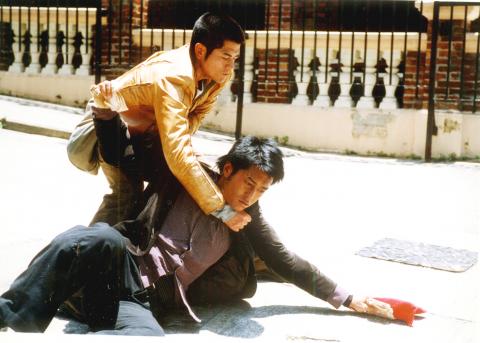

The three-time Golden Horse best director winner has also reaped critical acclaim overseas, with major film festivals including Cannes, Venice and Toronto premiering his works. Last October, the Toronto International Film Festival screened a retrospective on 19 of To’s iconic films, including The Mission (鎗火, 1999) and Election (黑社會, 2005), while the recent Far East Film Festival in Udine, Italy closed their 20th edition with a restored version of his 2004 judo drama, Throw Down (柔道龍虎榜).

“This is one of my favorite movies,” To says. “I made Throw Down at a time when Hong Kong was suffering from the SARS epidemic, and the morale of the people was low. But as the title Throw Down implies, you have to get back up.”

Photo courtesy of the Far East Film Festival

It’s an encouraging message that could likewise be conveyed to Hong Kong’s declining film industry, which now produces around 60 films annually — a far cry from its peak of 400 in the golden era of the early 1990s. Meanwhile, To has diversified by tackling different genres, with films such as romantic drama Linger (蝴蝶飛, 2008) and musical-comedy Office (華麗上班族, 2015).

But he is best known for his gritty, highly-stylized action thrillers that go deep into the dark underbelly of Hong Kong triad society, exploring enduring themes of brotherhood, loyalty and honor.

“The most important thing is to keep your own original ideas and never copy other people’s stuff,” he responds, when probed on his formula for success. “Since the triad genre already exists, I always try to create something different from what has already been shown by injecting my own personality and observations of life, so that people will notice that this is my movie.”

Photos courtesy of the Far East Film Festival

GUT INSTINCT

With his scripts always incomplete at the point of shooting, the auteur, who never studied filmmaking, relies on gut instinct and improvisation on set. He adds: “Every time I look at my lens, I see new ideas pop up; I breathe off all these new energies. That’s why I keep changing my script — to me, that’s the best way to make a movie.”

To, like many other directors, still prefers shooting on film over digital, though he’s not averse to the latest technological trends. For one, he embraces the idea of having more of his films acquired by Netflix — Three (三人行, 2016) and Election are already available for viewing on the global platform.

“I don’t mind my films not being shown on the big screen. The Internet, pay-per-view and streaming are opening up more opportunities for audiences worldwide to see films. As a filmmaker, I’m happy to participate in new platforms that show our works,” he says, adding that it would be nice to see his 2003 crime thriller, PTU, on Netflix.

NURTURING NEW TALENT

Audiences here and all over Asia may have to settle for watching To’s old films online for now — the director remains coy on the details of the anticipated third installment of his hit crime series Election. Having been relatively quiet for the past year, To says he is currently focusing his time on nurturing new talent in the Hong Kong Fresh Wave Short Film Program, which he founded in 2005.

“At that point in time, I felt that I was pretty well-established as a filmmaker. So I wanted to do something to give back to the Hong Kong film industry, like sharing my experiences with new filmmakers,” he says. “It’s my sincere wish that Fresh Wave directors can go out on their own and bring more new works in Hong Kong cinema.”

As for his next projects, To is not content with getting by and doing the bare minimum. “After 45 years, it’s not about the money anymore,” he adds.

“It’s about making a movie that I can feel will really represent myself, and one that will have an impact on future filmmakers. That’s my new goal for the future,” To says.

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful