July 31 to Aug. 6

To the Qing Empire, they were fan (番), or barbarians. The Japanese called them the Takasago, or high mountain people. And the Chinese Nationalist Party referred to them as shanbao (山胞), or mountain compatriots.

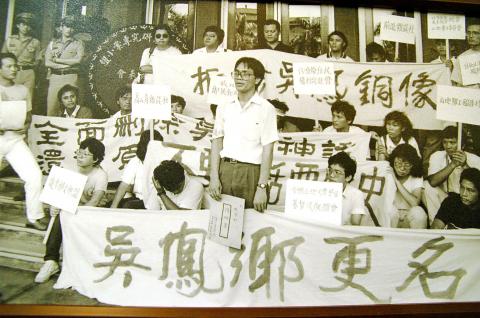

In late 1984, the Aborigines of Taiwan decided that they would no longer bear the designation handed to them by the colonizers. On Dec. 29, a group of 23 Aboriginal and Han Chinese intellectuals got together and formed the Taiwan Aboriginal Rights Association (台灣原住民權利促進會), with one of their demands being that the government officially call them yuanzhumin (原住民, or original inhabitants), which is the term used today.

Photo courtesy of Hsieh San-tai

“The organization was the first one that included the term ‘Aborigine’ in its name,” writes Icyang Parod in the book, Compilation of Historical Material on Taiwan’s Aboriginal Movement (臺灣原住民族運動史料彙編). Now minister of the Council of Indigenous Peoples, Icyang was a key figure in various early Aboriginal movements.

It seemed like a simple and harmless request, but the process took almost 10 years. On Aug. 1, 1994, National Assembly finally granted the request along with an article in the constitution to protect indigenous rights. Aboriginal activists continue to fight for various issues today, but the rectification of their designation was seen was seen as a major victory to a long-mistreated people. Since 2005, Aug. 1 has been observed in Taiwan as Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

A PURE NAME

Photo: Hsieh Wen-hua, Taipei Times

In 1983, along with two other Aboriginal National Taiwan University students, Icyang launched the publication High Green Mountain (高山青), which highlighted the danger of Aboriginal cultural extinction and called for Aborigines to start a self-help movement.

“Through looking at their own situation, they hoped to awaken an Aboriginal consciousness,” Iwan Nawi writes in the book, Taiwan’s Aboriginal Movement at the Legislative Yuan (原住民運動與國會路線). “Although this consciousness originated on campus, it quickly spread through the urban Aboriginal population as well as urban mainstream society.”

Icyang writes that the Aboriginal Rights Association was originally to be named “High Mountain Tribe Rights Association” (高山族權利促進會), but a month before the organization launched, current Kaohsiung Bureau of Education Director Fan Sun-lu (范巽綠) proposed that they use the term Aboriginal instead. The term was formally adopted after an intense debate during the organization’s first meeting.

Photo: Lu Chun-wei, Taipei Times

“It was a pure term because it had never been officially used before,” Icyang writes. “The use of the term symbolizes the fact that our organization not only sought to resolve tangible Aboriginal social issues, it also fought for our status as well.

“We not only want to have our people identify with being Aborigines, through the term we also want to let the Han Chinese know that this land originally belonged to us. We will not dwell on the methods through which they obtained this land, but they should at least respect our rights and status.”

The newly-formed Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) supported the movement, using the designation in its party constitution written in 1986. The same year, the Presbyterian Church also officially adopted the designation, and usage spread among the church’s roughly 80,000 Aboriginal members.

Photo: Taipei Times

CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGE

But the push for the government to formally eliminate “mountain compatriots” in favor of “Aborigines” did not take shape until 1991.

That year, the National Assembly convened to amend the constitution. One of the agenda items concerned guaranteed seats in the Legislature for “mountain compatriots.” If passed, this would be the first time the hated designation appeared in the constitution.

Icyang and other protestors marched to the National Assembly meeting grounds at Yangmingshan’s Zhongshan Hall, and after being blocked by security several times, managed to deliver their petition. They made several requests, but Icyang says that the designation change was the only one reported by the media. To his dismay, no action was taken.

The National Assembly convened again to amend the constitution a year later, and this time more than 1,000 protestors marched to Zhongshan Hall. Icyang writes that the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was hesitant to designate the Aborigines as the original owners of the land, because that would imply that the Han Chinese were a foreign people and the KMT a foreign regime, leading to further problems. The National Assembly then suggested zaozhumin (早住民, or earlier inhabitants) or xianzhumin (先住民, or first inhabitants), which the activists deemed unacceptable.

By the end of the session, Icyang and his people remained “mountain compatriots.”

The DPP backed the Aborigines during the constitution amendment session of 1994. In April, then-president Lee Teng-hui (李登輝), who had opposed the designation change in 1992, publicly addressed the “mountain compatriots” as Aborigines in a speech. This likely prompted the reticent KMT to add the designation change to their agenda as well.

In June, 3,000 people marched for Aboriginal rights. A month later Lee promised Aboriginal activists that they would get their wish. The assembly voted 196-63 in favor.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

“M yeolgong jajangmyeon (anti-communism zhajiangmian, 滅共炸醬麵), let’s all shout together — myeolgong!” a chef at a Chinese restaurant in Dongtan, located about 35km south of Seoul, South Korea, calls out before serving a bowl of Korean-style zhajiangmian —black bean noodles. Diners repeat the phrase before tucking in. This political-themed restaurant, named Myeolgong Banjeom (滅共飯館, “anti-communism restaurant”), is operated by a single person and does not take reservations; therefore long queues form regularly outside, and most customers appear sympathetic to its political theme. Photos of conservative public figures hang on the walls, alongside political slogans and poems written in Chinese characters; South

Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) announced last week a city policy to get businesses to reduce working hours to seven hours per day for employees with children 12 and under at home. The city promised to subsidize 80 percent of the employees’ wage loss. Taipei can do this, since the Celestial Dragon Kingdom (天龍國), as it is sardonically known to the denizens of Taiwan’s less fortunate regions, has an outsize grip on the government budget. Like most subsidies, this will likely have little effect on Taiwan’s catastrophic birth rates, though it may be a relief to the shrinking number of