Vonny Chen’s (陳雅芳) voice breaks as she talks about Taiwan’s long-time independent activists, even though she has lived her entire life in Indonesia.

“Sometimes I say I’m Taiwanese because my father’s blood is running through mine,” she says, adding that she loves Taiwan.

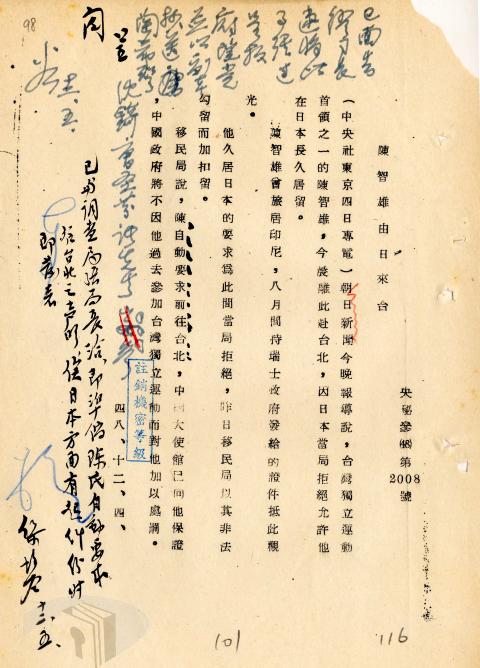

Chen does not feel optimistic about Taiwanese independence, citing China’s political and economic strength. But the “dream” carries emotional significance as her father, Chen Chih-hsiung (陳智雄), was the first independence activist to be executed, which occurred on May 28, 1963.

Photo courtesy of Sherry Huang

Although Chen, 67, is in poor health and doesn’t speak Mandarin, she insisted on visiting Taiwan last month for the unveiling of her father’s monument at Nantou County’s Holy Mountain Ecological Educational Park, where other human rights, democracy and independence activists are honored. She spent a month in Taiwan, traveling to Green Island where her father was incarcerated and meeting with independence activists and former political prisoners who knew her father. On the 54th anniversary of her father’s execution, she prayed in front of his ashes.

FROM HATRED TO PRIDE

Chen says she used to hate her father for abandoning the family, often thinking that he loved Taiwan more than his children. It wasn’t until she had her own child that she tried to contact her father, only to learn in 1979 through Taiwan’s representative office in Indonesia that he was dead. She made her first trip to Taiwan in 1980, but did not learn much because of martial law.

Photo courtesy of Linda Arrigo

It was only on her seventh trip, in 2013, that she learned the reason for his execution. She received documents about her father from the National Archives, including his will and final letter to his three children, which stated, “I died for the people of Taiwan,” in Japanese.

“I don’t know why [they] kept these letters for so many years without giving them to us, and why they preserved them when they didn’t care about them,” she says.

Chen also learned of the way her father was executed through his prison-mate Liu Chin-shih (劉金獅). Liu told Vonny Chen that a rag was stuffed in Chen Chih-hsiung’s mouth to prevent him from yelling “Long Live Taiwan Independence” and his feet cut off so he couldn’t stand with his head held high.

Photo courtesy of Sherry Huang

“I’m old, and it’s not easy for me to move on,” she says. “Every time I think of that, I feel heartbroken.”

Chen is now proud of her father, stating that she could never do what he did. She’s more upset that the government kept her father’s will, in which he asked a friend to take care of his children.

“When my father left my mother, we had nothing,” she says. “My father used all the money to help Taiwanese [in Indonesia]. My mother said she cooked a lot because they came to eat at our house. If they didn’t have anything, my father helped them.”

She wonders if life would have been different if the friend had received the news.

“[In a sense], they tried to kill us too,” she says.

NOT A HERO

Chen Chih-hsiung first arrived in Indonesia in 1945 as a translator for the Japanese army. He stayed in the country as a jewelry dealer after the war and, according to his daughter, traveled the area to buy weapons to support the Indonesian independence movement.

In 1946, he fell in love and eloped with his landlady’s niece, who was 16 at the time, but eventually returned to stay with her family. Vonny Chen, the second of three children, was born in 1949. Chen says her father had arranged for the family to leave Indonesia with him in 1951, but her grandmother prevented them from going to the bus stop. He would still visit every now and then, and Chen last saw him when she was seven years old.

“We only saw him for an hour because our grandmother was afraid he would kidnap us,” she says.

During those years, Chen Chih-hsiung worked closely with Japan-based independence activist Thomas Liao (廖文毅), serving as the Republic of Taiwan Provisional Government’s (台灣共和國臨時政府) ambassador to Southeast Asia. He later joined Liao in Japan, but the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) forced him back to Taiwan with help from Japanese authorities, who promised to leave him alone if he ceased his independence activities. He obviously did not, forming a group that aimed to “end the brutal reign of the KMT” in 1961.

Vonny Chen and her brothers visited Taiwan several times throughout the 1980s, finally tracking down an aunt who was a nun in Yilan. She learned through her aunt that Chen Chih-hsiung was executed, but was warned not to ask further questions.

In 2003, Chen and her family received NT$5 million from the government in compensation for his death, but no details were provided. It would take another 10 years for Chen to find out why her father died.

“It’s been a long journey full of tears,” she says.

Vonny Chen was surrounded by people who knew her father or shared his goal of Taiwan independence during her month in Taiwan, but she laments that outside of that circle, few people know who he is.

“Some say my father is a hero,” she says. “But for Taiwan, he’s not a hero. That’s why they killed him. My father would be Taiwan’s hero if it were independent. But if not, nobody knows about him.”

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)