After mostly singing Aboriginal-style songs with Chinese lyrics for the past few years with the band Hey!, Cemelesai Pasasauv is doing a complete turnaround. There are hardly any Aboriginal musical elements in his solo debut, Zemiyan, but the lyrics are written entirely in the Northern Paiwan language.

“I decided that it was enough that our culture is represented in the lyrics,” he says. “We don’t have to deliberately insert traditional elements into original music. This not only allows me to reach a larger audience, I also hope to show my tribespeople that our language can be sung in this way too.”

The album’s title means “dance” in Paiwan — which is often done by forming a circle. The English title is Circularity, and singing in Paiwan represents Cemelesai’s return to his origins.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“You can’t just enter the circle during a traditional dance, you have to be accepted,” Cemelesai, 28, says. “You can’t just barge in wearing many feathers on your head. You have to be humble. The importance of this is how do you return to where you’re from, hold hands with your family and tribespeople, form a circle and start dancing again.”

Released in December, the result is a collection of introspective and soulful guitar-and-piano folk pop tunes — which Cemelesai says is actually closer to his tribal music than what he calls “stereotypical Aboriginal music.”

“Traditional Paiwan music doesn’t have a lot of those bold and far-reaching vocals that people would expect,” he says. “Our music is slower. We listen to the bees, the river, the wind blowing through trees. A lot of our songs are about missing someone, sung softly under a tree. When you miss someone, would you be shouting loudly?”

Formally trained in classical opera and used to singing at the top of his lungs, this album represents a new direction for Cemelesai. In the liner notes, he writes, “This time, please listen to me sing softly.”

ENDANGERED LANGUAGE

Cemelesai admits that he is far from fluent in Northern Paiwan. He spoke it as a child, but gradually lost his ability after leaving his village to attend junior high school in Pingtung City.

“My family would tease me because of my Paiwan when I went home,” he says. “I became self-conscious that my Paiwan was getting worse, and eventually I would only speak to them in Chinese.”

This aversion continued until one day he realized that he could no longer understand what his grandmother, who only spoke Paiwan and Japanese, was saying.

“It was very scary,” he says. “They were chatting and telling stories, and I felt like I was from another planet. I could only understand basic words ... I realized that knowing one’s mother language affects how deep one can understand one’s culture.”

Cemelesai’s Paiwan has improved much since, but he’s still not at the level where he can write lyrics directly. He says he forms a story in his head first and takes it to a Paiwan language teacher, and they write the lyrics together. He then translates the lyrics back into Chinese for the album booklet, noting that a major difference between writing in Paiwan and Chinese is the use of metaphors.

“We say someone is as a beautiful as a flower,” he says. “Someone’s hair is long like a waterfall. It’s harder to directly describe these things like we do in Chinese.”

Cemelesai is confident that people who don’t understand Paiwan will still get his music.

“A lot of non-Paiwan people have told me the feeling they get from listening to the song, and what they think I’m trying to convey — and they’re usually spot on,” he says. “You don’t have to understand the lyrics. Listen to the music first. Feel it. Then you can look at the translations.”

His family has praised his efforts — but they still think his lyrics are too shallow, and Cemelesai still has much to learn. However, the truth is that while many Paiwan like him have taken an interest in preserving the language, the number of young speakers continues to decrease. The language is listed as “vulnerable” on the UNESCO list of endangered languages.

“Honestly, I don’t know how long our language will last, but we can only do what we can,” he says.

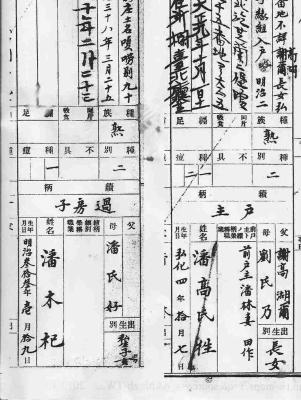

Feb. 9 to Feb.15 Growing up in the 1980s, Pan Wen-li (潘文立) was repeatedly told in elementary school that his family could not have originated in Taipei. At the time, there was a lack of understanding of Pingpu (plains Indigenous) peoples, who had mostly assimilated to Han-Taiwanese society and had no official recognition. Students were required to list their ancestral homes then, and when Pan wrote “Taipei,” his teacher rejected it as impossible. His father, an elder of the Ketagalan-founded Independence Presbyterian Church in Xinbeitou (自立長老會新北投教會), insisted that their family had always lived in the area. But under postwar

In 2012, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) heroically seized residences belonging to the family of former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁), “purchased with the proceeds of alleged bribes,” the DOJ announcement said. “Alleged” was enough. Strangely, the DOJ remains unmoved by the any of the extensive illegality of the two Leninist authoritarian parties that held power in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Taiwan. If only Chen had run a one-party state that imprisoned, tortured and murdered its opponents, his property would have been completely safe from DOJ action. I must also note two things in the interests of completeness.

Taiwan is especially vulnerable to climate change. The surrounding seas are rising at twice the global rate, extreme heat is becoming a serious problem in the country’s cities, and typhoons are growing less frequent (resulting in droughts) but more destructive. Yet young Taiwanese, according to interviewees who often discuss such issues with this demographic, seldom show signs of climate anxiety, despite their teachers being convinced that humanity has a great deal to worry about. Climate anxiety or eco-anxiety isn’t a psychological disorder recognized by diagnostic manuals, but that doesn’t make it any less real to those who have a chronic and

When Bilahari Kausikan defines Singapore as a small country “whose ability to influence events outside its borders is always limited but never completely non-existent,” we wish we could say the same about Taiwan. In a little book called The Myth of the Asian Century, he demolishes a number of preconceived ideas that shackle Taiwan’s self-confidence in its own agency. Kausikan worked for almost 40 years at Singapore’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, reaching the position of permanent secretary: saying that he knows what he is talking about is an understatement. He was in charge of foreign affairs in a pivotal place in