Aesthetically speaking, Le Moulin (日曜日式散步者) is a beautiful, unique and creatively executed piece that captures the spirit of the surrealist French-influenced, Japanese-educated Taiwanese poets of the 1930s, an experimental documentary that meshes tastefully recreated scenes, evocative sequences, carefully selected details, poetry readings, historical photos and footage and text to create a multifaceted feature film that is almost like an extensive, epic ballad.

The film focuses on the Le Moulin Poetry Society, founded in 1935 by Yang Chih-chang (楊熾昌), Lee Chang-juei (李張瑞) and Lin Hsiu-er (林修二), who were proponents of French surrealism but wrote in Japanese, as many of the Taiwanese elite did at the time. Le Moulin only lasted a year, but the story follows the writers’ literary endeavors and correspondence up to the end of Japanese rule and the demise of their art form during the White Terror era.

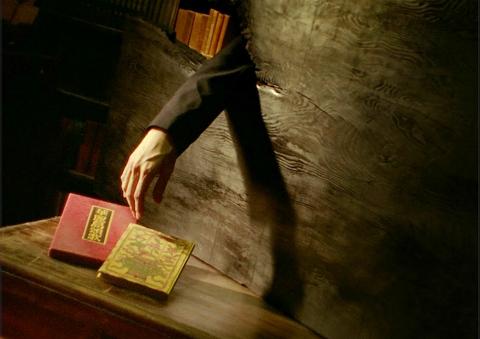

The film’s driving narrative is the recreated scenes of these literary compatriots interacting with each other, carrying a loose focus on Lin as it delves into his home life and marriage. Few faces are shown, just hands, movement and voices, which is an inventive way to represent a past era. Notable publications are cleverly inserted into recreated scenes, and there’s also great deal of poetry, whether in text or through readings. There’s also plenty of historical found footage, providing background of the conflict on cultural, political and economic fronts during turbulent times.

Photo courtesy of atmovies.com

Here’s the problem though: there’s a reason why poetry is often short and sweet. The concept for the film is refreshing — but no movie without a comprehensible storyline, tension or memorable characters should be 162 minutes long. The first hour or so was enjoyable — and it should have ended there, but the film continued to mosey on at a snail-like pace without an end in sight.

There is ground to cover, as the story spans several decades. But like any film, it can be condensed, and probably should have been. There is too much crammed in here, as the “story” is bogged down by poetic and picturesque stylings that are delightful at first but become tiresome after a while. Even the ending simply wouldn’t end after the plot had already concluded, with atmospheric scene upon atmospheric scene leading to suffocation.

Perhaps it is not a surprise that director Huang Ya-li (黃亞歷), a young experimental filmmaker, had only produced short films before Le Moulin. His 2008 work The Pursuit of What Was (物的追尋), lasted only 22 minutes, and the 2010 The Unnamed (代以名之的事物) ran for an even shorter 11 minutes. The difficulty in transition from shorts to feature is obvious here for the aforementioned reasons.

Huang “discovered” the poetry society in Lin’s thesis while doing research on Taiwanese surrealism. After half a year of research and field study, he decided to put the film together.

Alas, this is the type of film that infallibly garners rave reviews at the international festival circuits, promoting local arthouse filmmakers to churn out more uncompromising films like Le Moulin. There is definitely an audience for this type of film, but with such a promising idea — especially one depicting such a little known slice of Taiwanese history — one would wonder if it could have been edited to be a bit more suitable for the general public. But then, would that be compromising the director’s artistic vision? After all, it’s not meant to be a mainstream film, and maybe that’s why high art and pop culture don’t often mix.

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality