Taiwan in Time: July 4 to July 10

On the morning of July 5, 1959, four F-86 Sabre fighter planes departed from the Hsinchu Air Base, their mission a simple one — to patrol the airspace over the Matsu Islands, just off the coast of China.

It was not a combat mission, but the four Taiwan-based Republic of China (ROC) Air Force pilots were still advised to be careful, as there were reports of increased enemy People’s Republic of China (PRC) MiG-17 fighter plane activity in the area.

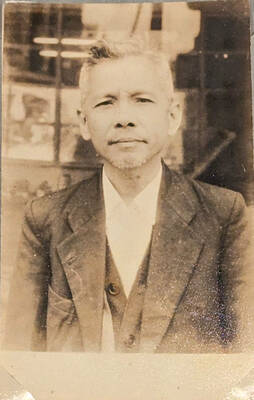

Photo: Wang Jung-hsiang, Taipei Times

The last major battle between ROC and PRC forces concluded on Oct. 5, 1958 with the end of the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis, but minor skirmishes continued to take place.

Most incidents were not meant to be combat missions -- the planes usually set out from Taiwan to either patrol the strait or take reconnaissance photos, but there was always the risk of running into the enemy.

Because of the success of the US-provided Sabres, the aircraft was nicknamed “MiG Buster” (米格剋星). The real advantage, however, was most likely their infrared-guided Sidewinder missiles, first used in a September 1958 skirmish that led to the destruction of 10 MiGs.

This is the story as told in Wang Li-chen’s (王立楨) book, Pilot Stories (飛行員的故事). The pilots noticed the presence of four enemy planes as they flew over Wuchiu Island (烏坵). They immediately prepared for combat, and after some maneuvering Captain Chang Yen-ming (張燄明) opened fire and shot down one of the MiGs.

As the remaining MiGs split up into two groups, so did the Sabres, who continued pursuit. At this time, another group of MiGs arrived, forcing Chang Kang-ling’s (張崗陵) group to give up the chase and go on the defensive. Wang writes that Chang made a 7.5G turn and plunged straight downward toward one of the planes and opened fire, shooting it down.

Meanwhile, Chang Yen-ming’s team also ran into additional enemy planes. Chang engaged in scissor maneuvering with an enemy plane, only to find two more heading his way. To get away, he flew at full speed toward the ocean — pulling up at the last minute. One of the enemy planes did not pull up in time and crashed.

Chang Yen-ming’s groupmate, Kuan Yong-hua (關永華) also engaged in battle on his own, finally downing a fourth enemy plane. Wang writes that as the enemy pilot parachuted out of his plane, Kuan slowed down, made a circle around the pilot and saluted him before flying off.

Reports seem to vary on this event — some say that five MiGs were downed, some say that the planes set out from Chiayi, and some say that one MiG was shot down by anti-aircraft artillery on one of the ROC-controlled islands.

Aerial battles after this incident were sparse, the next recorded one being when two ROC fighters shot down a MiG in February 1960.

Lee Chiun-rong (李俊融) and Lee Ching-yi (李靜宜) write in the study, Comparing the Development and Battle Results of the Nationalist and Communist Air Forces (國共空軍發展及戰果差異之比較) that PRC was going through the disastrous Great Leap Forward and the Great Famine during that time and had little energy to devote to coastal air patrols.

The final battle, and also the final direct military engagement of any kind between the two sides took place on Jan. 13, 1967.

By that time, Taiwan had upgraded to the F-104 Starfighter and China the MiG-19, and this was reportedly the first time the first and last time an ROC Starfighter would shoot down a MiG.

This was another reconnaissance mission, and on the way back, the Starfighters were attacked by a group of MiG-19s. They shot down two enemy planes before heading back to Taiwan — but Major Yang Ching-tsung (楊敬宗) somehow disappeared on the way home.

There are many theories about what happened (which we will not delve into), and until today, Yang’s fate is still a mystery.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name

There is no question that Tyrannosaurus rex got big. In fact, this fearsome dinosaur may have been Earth’s most massive land predator of all time. But the question of how quickly T. rex achieved its maximum size has been a matter of debate. A new study examining bone tissue microstructure in the leg bones of 17 fossil specimens concludes that Tyrannosaurus took about 40 years to reach its maximum size of roughly 8 tons, some 15 years more than previously estimated. As part of the study, the researchers identified previously unknown growth marks in these bones that could be seen only