Rice-growing techniques learned through thousands of years of trial and error are about to be turbocharged with DNA technology in a breakthrough hailed by scientists as a potential second “green revolution.”

Over the next few years farmers are expected to have new genome sequencing technology at their disposal, helping to offset a myriad of problems that threaten to curtail production of the grain that feeds half of humanity.

Drawing on a massive bank of varieties stored in the Philippines and state-of-the-art Chinese technology, scientists recently completed the DNA sequencing of more than 3,000 of the world’s most significant types of rice.

Photo: AFP/NOEL CELIS

With the huge pool of data unlocked, rice breeders will soon be able to produce higher-yielding varieties much more quickly and under increasingly stressful conditions, scientists involved with the project told AFP.

Other potential new varieties being dreamt about are ones that are resistant to certain pests and diseases, or types that pack more nutrients and vitamins.

“This will be a big help to strengthen food security for rice eaters,” said Kenneth McNally, an American biochemist at the Philippines-based International Rice Research Institute (IRRI).

Photo: AFP/NOEL CELIS

Since rice was first domesticated thousands of years ago, farmers have improved yields through various planting techniques. For the past century breeders have isolated traits, such as high yields and disease resistance, then developed them through cross breeding.

However, they did not know which genes controlled which traits, leaving much of the effort to lengthy guesswork.

The latest breakthroughs in molecular genetics promise to fast-track the process, eliminating much of the mystery, scientists involved in the project told AFP.

Better rice varieties can now be expected to be developed and passed on to farmers’ hands in less than three years, compared with 12 without the guidance of DNA sequencing.

Genome sequencing involves decoding DNA, the hereditary material of all living cells and organisms. The process roughly compares with solving a giant jigsaw puzzle made up of billions of microscopic pieces.

A multinational team undertook the four-year project with the DNA decoding primarily in China by BGI, the world’s biggest genome sequencing firm.

Leaf tissue from the samples, drawn mostly from IRRI’s gene bank of 127,000 varieties were ground by McNally’s team at its laboratory in Los Banos, near Manila’s southern outskirts, before being shipped for sequencing.

A non-profit research outfit founded in 1960, IRRI works with governments to develop advanced varieties of the grain.

THREATS TO RICE

Farmers and breeders will need the new DNA tools, which scientists take pains to say is not genetic modification, because of the increasingly stressful conditions for rice growing expected in the 21st Century.

While there will be many more millions to feed, there is expected to be less land available for planting as farms are converted for urban development, destroyed by rising sea levels or converted to other crops.

Rice-paddy destroying floods, drought and storms are also expected to worsen with climate change. Meanwhile, pests and diseases that evolve to resist herbicides and pesticides will be more difficult to kill.

And fresh water, vital for growing rice, is expected to become an increasingly scarce commodity in many parts of the world.

As scientists develop the tools necessary to harness the full advantages of the rice genome database, the hope is that new varieties can be developed to combat all those problems.

“Essentially, you will be able to design what properties you want in rice, in terms of the drought resistance, resistance to diseases, high yields and others,” said Russian bioanalytics expert and IRRI team member Nickolai Alexandrov.

FOOD REVOLUTION

Scientists behind the project hope it will lead to a second “green revolution.”

The first began in the 1960s as the development of higher-yielding varieties of wheat and rice was credited with preventing massive global food shortages around the world.

That giant leap to producing more food involved the cross-breeding of unrelated varieties to produce new ones that grew faster and produced higher yields, mainly by being able to respond better to fertilizer.

But the massive gains of the earlier efforts, which earned US geneticist Norman Borlaug the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970, have since reached a plateau.

Although the DNA breakthrough has generated much optimism, IRRI scientists caution it is not a magic bullet for all rice-growing problems, and believe that genetically modifying is also necessary.

They also warn that governments will still need to implement the right policies, such as in regards to land and water use.

One of the key priorities of IRRI is to pack more nutrients into rice, transforming it into a tool to fight ailments linked to inadequate diets in poor countries as well as lifestyle diseases in wealthier countries.

“We’re interested to understand the nutritional value... we’re looking into the enrichment of micronutrients,” Nese Sreenivasulu, the Indian head of the IRRI’s grain quality and nutrition center told AFP.

Nese believes Type-2 diabetes, which afflicts hundreds of million of people, can be checked by breeding for particular varieties of rice which when cooked will release sugar into the bloodstream more slowly.

IRRI scientists are also hoping to breed rice varieties with a higher component of zinc, which prevents stunting and deaths from diarrhea in rice-eating Southeast Asia.

The Lee (李) family migrated to Taiwan in trickles many decades ago. Born in Myanmar, they are ethnically Chinese and their first language is Yunnanese, from China’s Yunnan Province. Today, they run a cozy little restaurant in Taipei’s student stomping ground, near National Taiwan University (NTU), serving up a daily pre-selected menu that pays homage to their blended Yunnan-Burmese heritage, where lemongrass and curry leaves sit beside century egg and pickled woodear mushrooms. Wu Yun (巫雲) is more akin to a family home that has set up tables and chairs and welcomed strangers to cozy up and share a meal

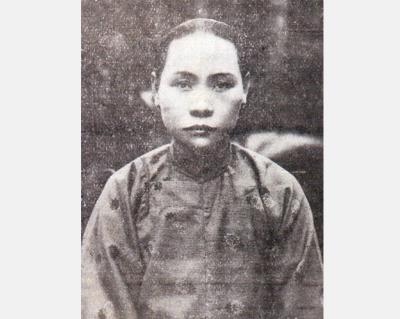

Dec. 8 to Dec. 14 Chang-Lee Te-ho (張李德和) had her father’s words etched into stone as her personal motto: “Even as a woman, you should master at least one art.” She went on to excel in seven — classical poetry, lyrical poetry, calligraphy, painting, music, chess and embroidery — and was also a respected educator, charity organizer and provincial assemblywoman. Among her many monikers was “Poetry Mother” (詩媽). While her father Lee Chao-yuan’s (李昭元) phrasing reflected the social norms of the 1890s, it was relatively progressive for the time. He personally taught Chang-Lee the Chinese classics until she entered public

Last week writer Wei Lingling (魏玲靈) unloaded a remarkably conventional pro-China column in the Wall Street Journal (“From Bush’s Rebuke to Trump’s Whisper: Navigating a Geopolitical Flashpoint,” Dec 2, 2025). Wei alleged that in a phone call, US President Donald Trump advised Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi not to provoke the People’s Republic of China (PRC) over Taiwan. Wei’s claim was categorically denied by Japanese government sources. Trump’s call to Takaichi, Wei said, was just like the moment in 2003 when former US president George Bush stood next to former Chinese premier Wen Jia-bao (溫家寶) and criticized former president Chen

President William Lai (賴清德) has proposed a NT$1.25 trillion (US$40 billion) special eight-year budget that intends to bolster Taiwan’s national defense, with a “T-Dome” plan to create “an unassailable Taiwan, safeguarded by innovation and technology” as its centerpiece. This is an interesting test for the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and how they handle it will likely provide some answers as to where the party currently stands. Naturally, the Lai administration and his Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) are for it, as are the Americans. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is not. The interests and agendas of those three are clear, but