Father Barry Martinson says there is an element of suffering to making art. He liked painting and writing when he was a child, but ever since he arrived in Chingchuan Village (清泉), an Aboriginal community nestled in the picturesque mountains of eastern Hsinchu, it has become more of a “mission” to beautify his surroundings, whether it be murals depicting Aboriginal life in his church or mosaics on the walls of a basketball court.

And now, he is on a mission to renovate the community’s main street.

“Some people just love to paint and paint. I don’t. I’ve got to have a motivation,” he says.

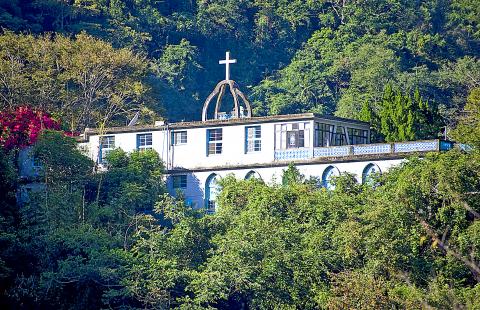

Photo courtesy of Barry Martinson

Martinson says in the 40 years he’s lived in Chingchuan, it has gone from attractive brick houses to drab concrete blocks and tin shacks. Neither he nor the villagers have the money to beautify the street, so Martinson is putting on an exhibition of his stained-glass paintings at Taipei 101 starting tomorrow.

Martinson says he has wanted to clean up the streets for a long time, especially since the village has become a tourist destination due to its hot springs and the former residences of writer San Mao (三毛) and former Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) marshal Chang Hsueh-liang (張學良), who served part of his house arrest here for kidnapping KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) in 1936.

“This is all people see of our village,” Martinson says. “As far as they’re concerned, Chingchuan is just a bunch of shacks. I think: ‘what a shame.’”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Neither the villagers, mostly laborers and farmers, nor Martinson had the funds to do anything, so he started making and selling stained-glass paintings. The remaining pieces — mostly consisting of movie scenes — will be displayed at Taipei 101 starting tomorrow, along with a choral performance by village children.

Martinson has three helpers for his work, which is done in the traditional way with multiple shadings and firings. The vivid, figurative pieces with detailed shading and thick black outlines can be lit up with a built-in LED light.

The original theme for this collection was “Faces of Love,” which not only includes Biblical images but also movie scenes and famous figures, including Audrey Hepburn and the Buddha.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“The idea was so the beautiful face of the village would come from the beautiful faces of the stained glass,” Martinson says.

YOU ARE YOUR HOUSE

Martinson is happy now when he leaves his church to visit with villagers, mostly Atayal Aborigines.

Three years ago, his paintings funded the youth community center, sprucing up an abandoned building in the process. For the past month, scaffolding has aligned the street as workers have installed geometric Atayal patterns to the facades of the concrete houses.

A large tribal mosaic is planned for the tallest, four-story building whose bleak gray side faces incoming traffic. An empty landing has been turned into a garden, with plants set to climb up an otherwise drab retaining wall.

“People were pleased that there was a tribal flavor without being too conspicuous,” Martinson says. “I wanted it to look like it’s been there all the time.”

Martinson says most of the project has been completed with local labor.

“The idea is to help people realize that this is a renovation not only of your exterior but your interior,” he says. “That their street is beautiful should help them feel pride about themselves. I always say, you are your house.”

Martinson’s plans for the village don’t end here. His next goal is to create a loop through the village for tourists to stroll around instead of going straight to the attractions. Then villagers can make some extra income by setting up stands outside their homes.

Jesuit priests can request to be transferred, and Martinson has thought of leaving many times, but each time, he’s decided against it.

“It’s my faith,” he says. “I don’t wear it on my sleeve, but we believe that when our superior sends us somewhere, it’s where God wants us to be. Then it’s the people ... and third, the nature.”

EXHIBITION NOTES

What: Love in the Movies Stained Glass Paintings

When: Tomorrow to Dec. 11

Where: Gallery 101 (in Taipei 101), 7, Sec 5, Xinyi Rd, Taipei City (台北市信義路5段7號)

Details: Auction on Dec. 11

On the Net: www.facebook.com/丁松青神父愛的容顏-1449027295406227/

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not