With an all-volunteer military and Americans at home being asked to make no real sacrifices, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan opened up a chasm between soldiers (“the other 1 percent”) and civilians. While troops were being killed and wounded “over there,” life “back here” went on very much the way it had before the September 11 attacks. Many recent fiction and nonfiction books about those wars have looked at that disconnect by examining the difficulties that veterans face upon returning home to an oblivious country, feeling alienated and cut off, and often still reeling from the physical and emotional traumas of combat.

War of the Encyclopaedists takes a different approach to this subject. This spirited novel was a collaboration between two friends: Christopher Robinson, who has an MFA from Hunter College and was a Yale Younger Poets prize finalist, and Gavin Kovite, an army lawyer and former infantry platoon leader. And it features a pair of heroes whose lives in many ways mirror the authors’ own.

Halifax Corderoy is about to start grad school at Boston University; his best friend, Mickey Montauk, is also about to start grad school, but finds his plans abruptly sidelined when his National Guard unit is activated and he is deployed to Baghdad. Their carefree college days together in Seattle, they begin to realize, have left them ill-prepared for the realities of grown-up life. They also find their friendship complicated by the intense relationships both develop with an unpredictable woman named Mani — one falls in love with her; the other weds her in a marriage of convenience.

In such respects, The Encyclopaedists seems to be emulating Truffaut’s classic movie Jules and Jim. It, too, maps a love triangle among two best friends and a tempestuous woman and is concerned with the disillusionments wrought by war and adulthood. It, too, shifts gears from a high-spirited comedy into something sadder and graver.

The Encyclopaedists doesn’t try, as Jules and Jim does, to trace a broader arc in its heroes’ lives but focuses instead on a pivotal year that will change Corderoy and Montauk’s understanding of themselves. At the same time, it does an adroit job of conjuring the 20-something bohemian world that they frequent in Seattle, and later in Boston, a world of millennials whose default setting is irony — where artworks and conversations and parties tend to have quotation marks around them, where artsy cool is both a social lubricant and a form of emotional armor.

Robinson and Kovite similarly use their gifts as social observers to gently satirize the two other rarefied worlds their heroes traverse. In the case of Corderoy, it is the pretentious realm of academia, where a professor warns him that he is not in grad school “purely for the pursuit of knowledge,” but must become “intimately familiar with post-structuralism, new historicism, phenomenology, and hermeneutics” if he wants to succeed. And in the case of Montauk, it is a forward operating base in Baghdad, around fall 2004, where common sense is often at odds with bureaucratic procedure, where the absurdities of the US occupation are cloaked in military lingo.

As a lieutenant in charge of a platoon, Montauk struggles to find his footing as a leader and self-consciously tries to learn how to project authority. He is soon dealing with more tangible concerns — the daily reality of IEDs and ambushes, and the loss of several comrades. The body of his favorite translator, Aladdin, is found dumped in the Tigris River, and one of his men is seriously wounded by a suicide bomber while stopping by a souvenir shop “weighing the pros and cons of getting a Lawrence of Arabia picture taken” as a birthday present for his mother. Many in the platoon were “losing it around the edges as the constant trickling of stress carved new and aberrant patterns into their personalities like underground streams in a limestone cave.”

Montauk and Corderoy stay in touch by editing and re-editing a Wikipedia page they created about themselves. The page, titled The Encyclopaedists, starts out as a sort of tongue-in-cheek joke, and gradually evolves into a mirror of — and parable about — their changing lives.

Montauk feels unable to communicate what being a soldier in Baghdad is like to anyone back home. Mani writes him a letter saying the war seems “weirdly fake” to her: “No one around here even thinks about it except to think how stupid it is, and how much they’re embarrassed by it, and how much they hate Bush, of course.”

Meanwhile, Corderoy has retreated into a narcissistic, Oblomovian existence. He pines over Mani, compares his life to “a mediocre movie,” even desultorily contemplates suicide. He soon drops out of grad school and tries scraping by on money earned by being a medical study guinea pig.

The plotting of this novel can feel ad hoc and overly stage-managed at the same time, but in a breezy, intimate sort of way. The authors have created an America and an Iraq in which people seem to cross paths with a startling ease (as characters do in, say, Larry McMurtry’s Old West). Tricia, Corderoy’s former roommate who has gone to Baghdad as a freelance writer, runs into (or contrives to run into) Montauk, whom she hooked up with one night back in Boston; and her translator, who is meant to help provide independent confirmation of evidence relating to Aladdin’s murder, turns out to know one of the people at the center of the investigation.

But if such coincidences and the story’s sometimes strained Wikipedia conceit can be distracting, Robinson and Kovite have nonetheless written a captivating coming-of-age novel that is, by turns, funny and sad and elegiac — a novel that leaves us with some revealing snapshots of America, both at war and in denial, and some telling portraits of a couple of millennials trying to grope their way toward adulthood.

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

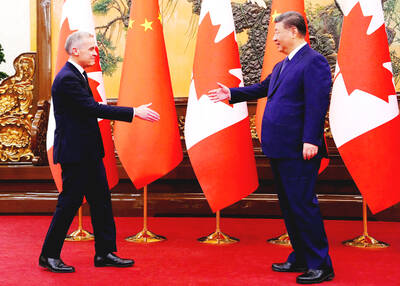

Britain’s Keir Starmer is the latest Western leader to thaw trade ties with China in a shift analysts say is driven by US tariff pressure and unease over US President Donald Trump’s volatile policy playbook. The prime minister’s Beijing visit this week to promote “pragmatic” co-operation comes on the heels of advances from the leaders of Canada, Ireland, France and Finland. Most were making the trip for the first time in years to refresh their partnership with the world’s second-largest economy. “There is a veritable race among European heads of government to meet with (Chinese leader) Xi Jinping (習近平),” said Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, director