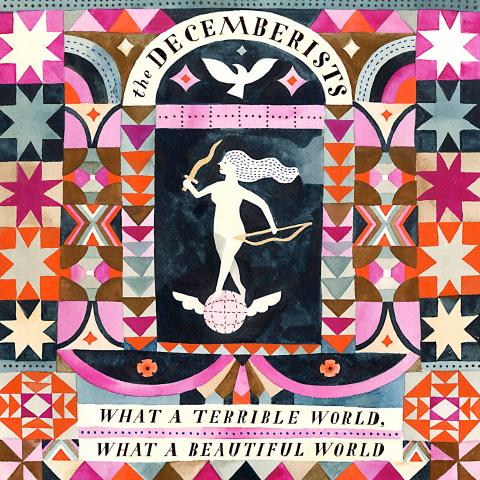

What A Terrible World, What A Beautiful World

The Decemberists

Capitol

Colin Meloy, the grandiloquent bard at the heart of the Decemberists, plants his silver tongue firmly in cheek at the start of What a Terrible World, What a Beautiful World, the group’s new album. By way of a deadpan disclaimer titled The Singer Addresses His Audience — “We had to change some, you know, to belong to you,” he sings, briefing the fervent faithful — the album opens knowingly, making an end run around at least one line of critique.

This is the seventh album by the Decemberists, an indie-folk troupe so closely associated with the earnest creative energies of Portland, Oregon, that the city has declared an official “Decemberists Day” to usher in the album’s release. The previous Decemberists album, The King Is Dead, from 2011, entered the Billboard album chart at No. 1 and yielded a couple of Grammy nominations. More than a few dates on the band’s coming tour have sold out, including a show at the Beacon Theater in New York on April 6.

Still, any throat-clearing about progression in these songs would best be taken in stride. Even Anti-Summersong — a reference to Summersong, a cherished bauble from the band’s back catalog — rings coy in its refusals. “So long,” Meloy chirps. “Farewell/Don’t everybody fall all over themselves.” For a band of such bookish and fanciful repute, this is a dose of puckish self-awareness and strategic misdirection.

On the whole, What a Terrible World, What a Beautiful World strikes a note of pop concision and maturity, building on what worked on The King Is Dead. Lyrically, there are fewer thistles and minarets and palanquins — and, musically, less digressive excess — than once made up the Decemberists’ trademark style.

Make You Better is about as lean an indie-rock single as the band has produced; it has a near equal, for sheer catchiness, in The Wrong Year. And the retro sheen of Philomena lights a snapshot of adolescent sexual awakening that for Meloy, feels startlingly frank. Along similar lines, but more in character, is Lake Song, in which he recalls a moment when he was “17 and terminally fey,” but ablaze with yearning.

Meloy has said that this album developed unhurriedly, with songs arriving in batches, adhering to no overarching concept. That’s refreshing, as are a couple of songs that acknowledge his perspective as a parent: Better Not Wake the Baby, a dose of sly gallows humor, and 12/17/12, which could be its tonal opposite.

Written shortly after US President Barack Obama addressed the nation following the school shootings in Newtown, Connecticut, the song comes from a shaken place, with Meloy despairing of the news while counting his blessings. What little artifice lurks in the song, which provides this album with its title, manages not to dampen its openhearted sentiment. And if that counts for a change, it’s a welcome one.

— NATE CHINEN, NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Moonlight

Hanni El Khatib

Innovative Leisure

Two Brothers, the last song on the new Hanni El Khatib album, Moonlight, starts out with a slithery, sloppy guitar line, soon buffeted by a bubbly, rumbling punk-funk bass line. “I lost two brothers this year/I hope they died without fear,” he sings, almost flirtatiously, as if his eyes were just barely open. A bit later, the song is disrupted by an interlude of guitars that crank and bend like a choking engine, then disappear just as fitfully.

El Khatib’s garage rock has never been completely faithful to tradition, but it has also never been this loose or appealing. Moonlight is his third album, and also his most convincing, finding a middle ground between the competing excesses of his first two. His 2011 debut, Will the Guns Come Out, had a goofy swing, with vocals like a fun house mirror Tom Waits. In 2013 came Head in the Dirt, which was the stern schoolteacher to the debut’s restless kid. It was produced by Dan Auerbach of the Black Keys, who imposed a one-size-fits-all approach onto El Khatib, making him cleaner and bigger and bluesier and far less interesting.

Moonlight thoroughly scrapes off that sheen, letting El Khatib breathe freely. All he retained from that experiment was a sturdier sense of songcraft, but with that skeleton as an anchor, he’s as relaxed as ever. On the title track, the background vocals seem to be walking woozily in the trail of the leads. Chasin’ is like a boom-bap Kinks record — “I just want to taste/The sweat off your skin,” he pants — and Servant opens with a crisp drum break and shifts into naive chanting. On Melt Me, El Khatib plays brash guitar while spitting filthy come-ons: “Come over and melt me/Like an ice cream cone/On the street in the sun.”

Throughout the album, there’s ample blank space — El Khatib’s preferred mode is strategic incompleteness. That way, when he stakes out his bold territorial claims on garage rock’s fringes, there’s nothing that gets in the way.

— JON CARAMANICA, NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

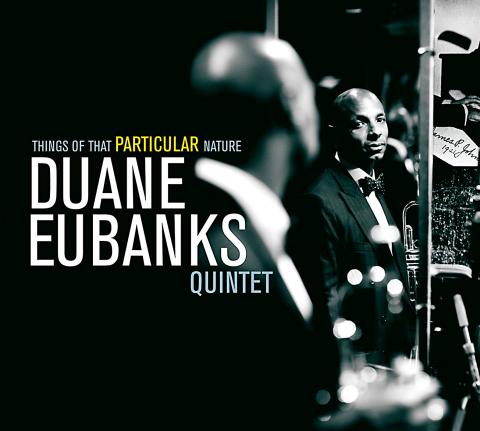

Things of That Particular Nature

Duane Eubanks Quintet

Sunnyside

The jazz trumpeter Duane Eubanks has spent much of his career in shadow. Growing up in Philadelphia, he followed in the path of two abundantly gifted musical brothers: Robin, a trombonist, and Kevin, a guitarist. He might best be known today for the high caliber of his sideman appointments, in groups like the Dave Holland Big Band and Mulgrew Miller’s Wingspan; his own first and second albums as a leader were released roughly 15 years ago.

So his third, Things of That Particular Nature, arrives with some sense of occasion, though Eubanks, who will turn 46 this week, still doesn’t cut the figure of a thrust-and-parry hotshot on the horn. He favors a school of post-bop clarity perfected by the likes of Woody Shaw, and later codified by the likes of Terence Blanchard: plungingly assertive but governed by a rational cool, in no rush to reinvent the wheel.

He wisely made the new album a showcase for some peers of longstanding rapport: the tenor saxophonist Abraham Burton, the pianist Marc Cary, the vibraphonist Steve Nelson, the bassist Dezron Douglas and the drummer Eric McPherson. He also took the chance to air out his original tunes, each one a sturdy, unassuming vehicle for the band. The album sounds, appealingly, as if it could have been banged out in an afternoon.

Eubanks has a focused but not especially glowing tone, and he can convey the cottony mellowness of a flugelhorn even when he isn’t playing one. (In this he sometimes recalls a former mentor, Johnny Coles.) When he does opt for flugelhorn, as on a brooding waltz, Aborted Dreams, the emphasis falls on his earthy purity of sound.

His rhythm section, spearheaded by Cary, makes expeditious work out of the material, turning a simple tune like As Is into a pocket epic. Slew Footed unfurls in a mutable series of tempos, the beat expanding or contracting at each soloist’s whim. And the odd flash of funk — like Dance With Aleta, which suggests a backing track from an old Gamble and Huff production — works just as handily as the album’s lone cover, an extra-sensitive reading of Miller’s Holding Hands, flugelhorn and all.

— NATE CHINEN, NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Feb. 9 to Feb.15 Growing up in the 1980s, Pan Wen-li (潘文立) was repeatedly told in elementary school that his family could not have originated in Taipei. At the time, there was a lack of understanding of Pingpu (plains Indigenous) peoples, who had mostly assimilated to Han-Taiwanese society and had no official recognition. Students were required to list their ancestral homes then, and when Pan wrote “Taipei,” his teacher rejected it as impossible. His father, an elder of the Ketagalan-founded Independence Presbyterian Church in Xinbeitou (自立長老會新北投教會), insisted that their family had always lived in the area. But under postwar

In 2012, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) heroically seized residences belonging to the family of former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁), “purchased with the proceeds of alleged bribes,” the DOJ announcement said. “Alleged” was enough. Strangely, the DOJ remains unmoved by the any of the extensive illegality of the two Leninist authoritarian parties that held power in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Taiwan. If only Chen had run a one-party state that imprisoned, tortured and murdered its opponents, his property would have been completely safe from DOJ action. I must also note two things in the interests of completeness.

Taiwan is especially vulnerable to climate change. The surrounding seas are rising at twice the global rate, extreme heat is becoming a serious problem in the country’s cities, and typhoons are growing less frequent (resulting in droughts) but more destructive. Yet young Taiwanese, according to interviewees who often discuss such issues with this demographic, seldom show signs of climate anxiety, despite their teachers being convinced that humanity has a great deal to worry about. Climate anxiety or eco-anxiety isn’t a psychological disorder recognized by diagnostic manuals, but that doesn’t make it any less real to those who have a chronic and

When Bilahari Kausikan defines Singapore as a small country “whose ability to influence events outside its borders is always limited but never completely non-existent,” we wish we could say the same about Taiwan. In a little book called The Myth of the Asian Century, he demolishes a number of preconceived ideas that shackle Taiwan’s self-confidence in its own agency. Kausikan worked for almost 40 years at Singapore’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, reaching the position of permanent secretary: saying that he knows what he is talking about is an understatement. He was in charge of foreign affairs in a pivotal place in