The year was 1991. American film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum was experiencing his first authentic night out in Taipei at a late night karaoke party hosted by renowned Taiwanese film director Hou Hsiao-Hsien (侯孝賢). Fueled by bottles of cognac and a generous supply of betel nuts, the duo belted out Beatles songs until 3am before stumbling home.

Having reviewed Dust in the Wind (戀戀風塵, 1986) and A City of Sadness (悲情城市, 1989) for the Chicago Reader, long-time film critic Rosenbaum was no stranger to Hou’s work. But being in Taipei for the Asia-Pacific Film Festival gave him a better appreciation of the local culture, history and setting.

“I was able to spend my 19 days there less as a tourist than as a part of everyday life in Taipei,” said Rosenbaum, who was in New York this past week for the retrospective “Also Like Life: The Films of Hou Hsiao-hsien” at the Museum of the Moving Image.

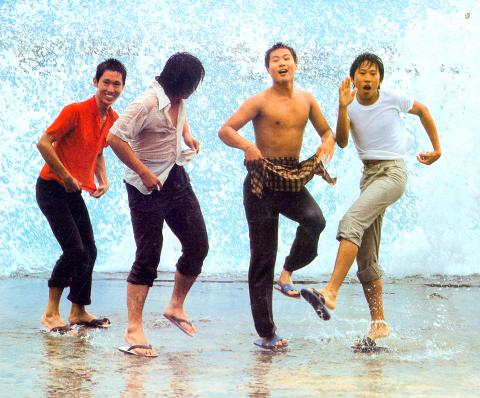

Photo Courtesy of Center for Moving Image Arts, Bard College

TAIWANESE NEW WAVE

The early 1990s was a crucial time for a film critic to be visiting Taiwan since the industry had recently undergone major changes. In contrast to kungfu and melodrama, the New Wave of the 1980s introduced an element of realism to Taiwanese cinema akin to Italian neorealism, and Hou was the central figure driving the movement.

Rather than presenting viewers with drawn-out fight scenes or heart-wrenching tragedies, films of this period dealt with the everyday realities of working class life in Taiwan. Concentrating on such banalities may not seem too exciting, but the movement was groundbreaking because up until then, the films being produced lacked an emphasis on Taiwanese history.

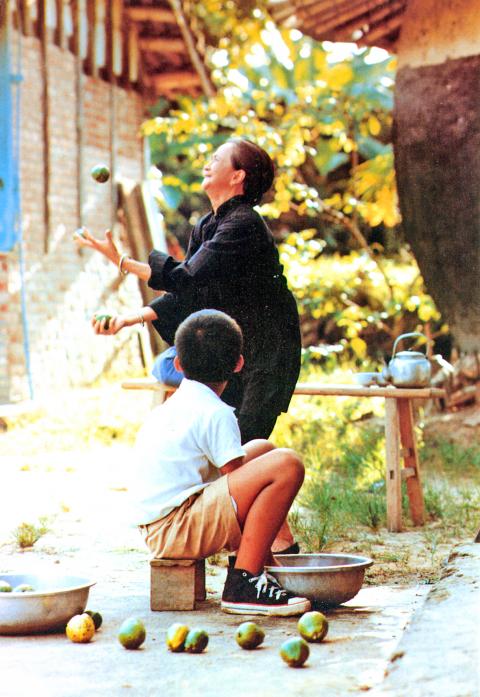

Photo Courtesy of Center for Moving Image Arts, Bard College

As Rosenbaum told the Taipei Times, “Taiwanese history is such a taboo subject that when it gets ‘discovered’ it’s very important.”

RETROSPECTIVE

Organized by Taiwan’s Ministry of Culture, the Taiwan Film Institute, Taipei Cultural Center in New York and the Center for Moving Image Arts at Bard College, the touring retrospective “Also Like Life” is currently in New York until Oct. 17 before making stops in other US cities.

Photo Courtesy of Center for Moving Image Arts, Bard College

Film critics and organizers of the retrospective are hoping that it will raise awareness of Taiwanese history amongst American audiences.

“Although Hou is very widely recognized among American cinephiles as a master, his mainstream reputation in the US remains unfortunately limited, because of the low distribution of his films and the confused and partial understanding in the US of Taiwanese history,” Rosenbaum said.

Richard Suchenski from Bard College also noted that the distribution of foreign art cinema in North America over the past decade in particular has been increasingly sparse. As the main organizer of the retrospective, he spent two years searching for and compiling Hou’s films on the best possible 35mm prints in preparation for the retrospective.

Suchenski told the Taipei Times that “this is a very rare opportunity to see these remarkable films projected and I am thrilled that so many people are taking advantage of it.”

He added that the screenings have been attracting “very diverse audiences that include many young cinephiles.”

‘THE SANDWICH MAN’ AND THE TAIWANESE IDENTITY (CRISIS)

The Oct. 5 screening of The Sandwich Man (兒子的大玩偶, 1983) drew a diverse mixture of film buffs. The majority of viewers were not Taiwanese. The choice of film was interesting because Hou’s segment of the three-part film is almost entirely in Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese). Furthermore, it presents viewers with a heads-on confrontation of the question of what it means to be Taiwanese.

A compilation of three vignettes from Hou and directors Tseng Chuang-hsiang (曾壯祥) and Wan Jen (萬仁), The Sandwich Man explores the humdrum experience of working class life in 1960s Taiwan with a simplicity that is beautiful and intriguing.

As Suchenski said, “salient features of Hou’s cinema include elegantly staged long takes and the precise delineation of quotidian life.”

In other words, each vignette is not so much about dramatizing the tragic dimensions of poverty, but rather exploring how the characters find ways to be happy despite their seemingly abject condition living in “exile.” In doing so, the subjects begin to form a new social identity — a Taiwanese identity.

“The Sandwich Man expresses the existential dilemma of being Taiwanese better than any other film — the problem that arises from pretending to be someone else temporarily and then finding that this temporary identity had become one’s main social identity,” Rosenbaum said.

Hou may not be as famous as Ang Lee (李安) is in the US, but his films, as the retrospective has shown, have played a pivotal role in the redefinition of Taiwanese identity.

As for the drunken karaoke scene which Rosenbaum recalled from his 1991 visit — it could easily have been set in present day Taipei, except the cognac would be replaced with something more local, perhaps Taiwan Beer.

Last week writer Wei Lingling (魏玲靈) unloaded a remarkably conventional pro-China column in the Wall Street Journal (“From Bush’s Rebuke to Trump’s Whisper: Navigating a Geopolitical Flashpoint,” Dec 2, 2025). Wei alleged that in a phone call, US President Donald Trump advised Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi not to provoke the People’s Republic of China (PRC) over Taiwan. Wei’s claim was categorically denied by Japanese government sources. Trump’s call to Takaichi, Wei said, was just like the moment in 2003 when former US president George Bush stood next to former Chinese premier Wen Jia-bao (溫家寶) and criticized former president Chen

As I finally slid into the warm embrace of the hot, clifftop pool, it was a serene moment of reflection. The sound of the river reflected off the cave walls, the white of our camping lights reflected off the dark, shimmering surface of the water, and I reflected on how fortunate I was to be here. After all, the beautiful walk through narrow canyons that had brought us here had been inaccessible for five years — and will be again soon. The day had started at the Huisun Forest Area (惠蓀林場), at the end of Nantou County Route 80, north and east

A six-episode, behind-the-scenes Disney+ docuseries about Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour and Rian Johnson’s third Knives Out movie, Wake Up Dead Man, are some of the new television, films, music and games headed to a device near you. Also among the streaming offerings worth your time this week: Chip and Joanna Gaines take on a big job revamping a small home in the mountains of Colorado, video gamers can skateboard through hell in Sam Eng’s Skate Story and Rob Reiner gets the band back together for Spinal Tap II: The End Continues. MOVIES ■ Rian Johnson’s third Knives Out movie, Wake Up Dead Man

Politics throughout most of the world are viewed through a left/right lens. People from outside Taiwan regularly try to understand politics here through that lens, especially those with strong personal identifications with the left or right in their home countries. It is not helpful. It both misleads and distracts. Taiwan’s politics needs to be understood on its own terms. RISE OF THE DEVELOPMENTAL STATE Arguably, both of the main parties originally leaned left-wing. The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) brought together radicals, dissidents and revolutionaries devoted to overthrowing their foreign Manchurian Qing overlords to establish a Chinese republic. Their leader, Sun Yat-sen