From Day 1

Travis Porter

Teatro Carlo Felice, Genoa

Porter House/RCA

There’s beauty in diversity, sure, but there can be beauty in single-mindedness, too. Over the past few years the three men of the Atlanta hip-hop group Travis Porter — Quez, Ali and Strap — have become auteurs of the strip club, making buoyant, electrifying soundtrack music for late nights full of tossed-in-the-air dollar bills. What Too Short was to 1980s corner walkers, this group is to the modern-day pole dancer.

The apotheosis of the style was Make It Rain, originally released in 2010 and one of the great hip-hop anthems of recent years. A thumping, swerving, punchy number, it was salacious and comic in equal measure, a genuine triumph.

That song closes out From Day 1, the long-in-the-cooker major-label debut from this group, and it sets the tone as well. From Pop a Rubber Band to Wobble to songs with unprintable titles, these men know their milieu; they never met a stripper they didn’t want to rap about. This is an exuberantly raunchy album but also an intuitively musical one. Quez in particular has a mature gift for melody — he’s lighthearted in tone, adding a sense of fun to the proceedings. Ali can sound testy and saucy and Strap, with his rich accent, often sounds like he’s swallowing his words.

Songs like Ballin’, with their ostentatious swoops and turns in vocal delivery, recall rappers like Nelly and Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, Midwesterners who bent hip-hop into new shapes. And songs like Ayy Ladies offer more relaxed flirtation, away from the pole.

Only a pair of songs near the end of the album, Party Time and That Feeling, appear to be reaching for a broader idea, trading strip-club throbbing for pop-ear breeze. But here, the rappers sound loose, almost uncomfortable. They want to go back to the club.

— JON CARAMANICA, NY Times News Service

Carrera

Guillermo Klein and Los Guachos

Sunnyside

Guillermo Klein, the Argentine composer, arranger, pianist and bandleader, has long squared his art against a system of rhythmic convolution, cerebral and multi-layered but also bodily engaged. He hasn’t always had comparable use for strong, evocative melody, but his priorities seem to have shifted recently. Carrera, his captivating new album, contains some of his most tuneful work, without backtracking on any previous polymetric advances. The adjustment feels distinctly personal.

And maybe it is. Carrera largely consists of themes composed just before and after Klein’s return to Buenos Aires after a long stint in Barcelona, Spain. So on some level this is his homecoming album. It also follows his deep inquiry into the Argentine folklorist Cuchi Leguizamon, in performance and on the 2010 album Domador de Huellas. Melody was a core concern on that album, however Klein chose to reframe it.

His exacting, elastic band, Los Guachos, knows how to respond to even his most nuanced signals. But while some compositions here employ sly rhythmic subversions like the floating opener, Burrito Hill, and an arrangement of Alberto Ginastera’s Piano Sonata Op. 22 the band finds greater traction in lyricism.

So the tricky pulse of a ballad called Mariana, with its implication of five against four, all but dissolves in the face of an essay by Chris Cheek on tenor saxophone. Something analogous happens with another tenor, Bill McHenry, on a circuitous tune called ArteSano, and with the alto saxophonist Miguel Zenon on a flowing but urgent art song, Moreira, also featuring Klein on vocals.

Klein has been singing on his albums for years, in what often suggested a non-style, too casual and unpolished to seem otherwise. That’s different here too, especially on Globo, a melancholy ballad sung carefully in octaves with Zenon; and on a version of the tango standard Los Mareados, about star-crossed lovers attempting to drink away their fate. There have been many melodramatic readings of Los Mareados, but Klein wisely goes the other route: confiding, deliberate and direct.

— NATE CHINEN, NY Times News Service

Internal Logic

Grass Widow

HLR

The women in the San Francisco trio Grass Widow sing in clear and pretty harmonies over buzzing, nettlesome music — thin, staccato, slightly dissonant. It’s a group sound that’s counterintuitive all the time: reverbed and reassuring on the top, dry and interrogative on the bottom.

That’s a really good idea, but Grass Widow has stretched it about as far as it can go. Its limitations were apparent from the trio’s beginnings three years ago but seemed fresh or accidental. At this point, on Internal Logic, the band’s third full-length album, they amount to a kind of grim commitment. To what? To semiproficiency, to plainness, maybe even to the abrogation of pleasure.

Oh, it’s not as bad as all that. There’s been some growth. The vocal patterns among band members (the bassist Hannah Lew, the guitarist Raven Mahon and the drummer Lillian Maring) have become stronger and more careful, whether in unison, closer harmony or counterpoint. And the best of this album’s tightly composed songs — Under the Atmosphere, Spock on Muni — have moments of beauty in their choruses. But inasmuch as Grass Widow evokes bands from various postpunk movements since the late 70s — Wire, the Breeders, the Raincoats, Salem 66 — its selective approval of pop’s sweetness seems filtered through outside sources rather than felt firsthand.

Conceptually, Internal Logic is all set. But something’s missing here, and it’s something to do with music alone: sound, feeling, groove, attack, dynamics. The brittle, attenuated feeling of this album becomes wearying, like a three-course meal of nothing but grapefruit.

— BEN RATLIFF, NY Times News Service

The Absence Verve

An alternate title for The Absence, Melody Gardot’s spellbinding third studio album, might be “Wanderlust,” so immersed is it in the cultures of Portugal, Argentina and Brazil, places she visited in a protracted journey of musical discovery. The varying textures of songs, mostly written in English and Portuguese with some French and Spanish, are so fluid and finely tuned to the senses that listening to a song like Lisboa is like strolling through the city’s side streets captivated by the sounds of church bells and children at play while inhaling its exotic scents. The song whispers of history, of secrets sealed in ancient cellars and buried under cobblestones.

Gardot’s chief collaborator in this exploration of faraway places and the ebb and flow of erotic connections made during travel is the Brazilian-born session guitarist and film composer, Heitor Pereira. Pereira occasionally sings with Gardot in a voice that echoes Caetano Veloso and Joao Gilberto. On the love song, Se Voce Me Ama, their soft, husky murmurs mingle with an astounding intimacy.

Without quite settling into a particular style, the music embraces Portuguese fado, tango and light samba in acoustic guitar arrangements through which strings weave and in out as Gardot reflects on the vicissitudes of love. There is happiness: in the lilting Mira, she exults “in the joy that I feel like a sweet morning dew.” And there is deep sadness: in So We Meet Again My Heartache she embraces her yearning shadow self, the two “bound together by the breaking of a tired and torrid heart.”

Impossible Love acknowledges that even the flame of passion cannot burn brightly for very long. If I Tell You I Love You is the warning of a femme fatale not to believe her endearments. In the bitterly accusatory Goodbye, the album’s closest thing to a blues, she growls her contempt for a lover she regards as a naive fool.

The Absence is an album of seductive, mysterious atmospheres conjured by a pop-jazz singer whose audacity, raw talent and intense feeling recall the young Rickie Lee Jones, even though the two have little in common beyond a fierce individuality.

— STEPHEN HOLDEN, NY Times News Service

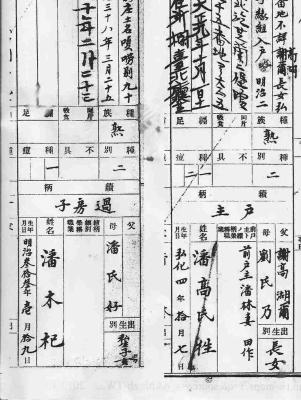

Feb. 9 to Feb.15 Growing up in the 1980s, Pan Wen-li (潘文立) was repeatedly told in elementary school that his family could not have originated in Taipei. At the time, there was a lack of understanding of Pingpu (plains Indigenous) peoples, who had mostly assimilated to Han-Taiwanese society and had no official recognition. Students were required to list their ancestral homes then, and when Pan wrote “Taipei,” his teacher rejected it as impossible. His father, an elder of the Ketagalan-founded Independence Presbyterian Church in Xinbeitou (自立長老會新北投教會), insisted that their family had always lived in the area. But under postwar

In 2012, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) heroically seized residences belonging to the family of former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁), “purchased with the proceeds of alleged bribes,” the DOJ announcement said. “Alleged” was enough. Strangely, the DOJ remains unmoved by the any of the extensive illegality of the two Leninist authoritarian parties that held power in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Taiwan. If only Chen had run a one-party state that imprisoned, tortured and murdered its opponents, his property would have been completely safe from DOJ action. I must also note two things in the interests of completeness.

Taiwan is especially vulnerable to climate change. The surrounding seas are rising at twice the global rate, extreme heat is becoming a serious problem in the country’s cities, and typhoons are growing less frequent (resulting in droughts) but more destructive. Yet young Taiwanese, according to interviewees who often discuss such issues with this demographic, seldom show signs of climate anxiety, despite their teachers being convinced that humanity has a great deal to worry about. Climate anxiety or eco-anxiety isn’t a psychological disorder recognized by diagnostic manuals, but that doesn’t make it any less real to those who have a chronic and

When Bilahari Kausikan defines Singapore as a small country “whose ability to influence events outside its borders is always limited but never completely non-existent,” we wish we could say the same about Taiwan. In a little book called The Myth of the Asian Century, he demolishes a number of preconceived ideas that shackle Taiwan’s self-confidence in its own agency. Kausikan worked for almost 40 years at Singapore’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, reaching the position of permanent secretary: saying that he knows what he is talking about is an understatement. He was in charge of foreign affairs in a pivotal place in