I experienced a number of Proustian madeleine moments while sitting in front of Jeng Jun-dian’s (鄭君殿) Louise, a painting of a blonde cherubic girl emerging from a body of water. The painting, one of almost two dozen currently on display at Eslite Gallery (誠品畫廊) in Taipei, elicited memories, if only briefly, of the crystal clear lakes I used to swim in during my youth. Another, Casseroles 1 (鍋子 1), a large-scale still life of kitchen pots and pans, made my stomach rumble with thoughts of my mother preparing a Sunday dinner. That’s what Jeng’s paintings do: they evoke in the mind of the viewer the domestic simplicity and innocence of times past.

But they do so while avoiding any nostalgic, suburban sentimentality because Jeng’s technique keeps the viewer’s gaze within a logical contour of line and color, which, depending on your distance from the painting, shifts back and forth from a lyrical realism to an almost geometric abstraction. It’s this formal multiplicity of perspectives that had the curious effect of snapping me back into the present.

It’s been four years since Jeng held his last solo show, and judging by the number of circular red stickers (indicating a sale) in this exhibition, titled Day In, Day Out (日常生活), the show is a resounding success. Perhaps this is due to the hype that Eslite Gallery has become adept at generating. Yet there is a confidence of style and maturity of technique in this show that were not fully realized in Jeng’s previous works.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

Jeng’s early landscapes expressed a neo-impressionist sensibility of rich earthy colors that emphasized the play of light off reflective surfaces: think later Edouard Manet, though with a greater use of blacks and grays.

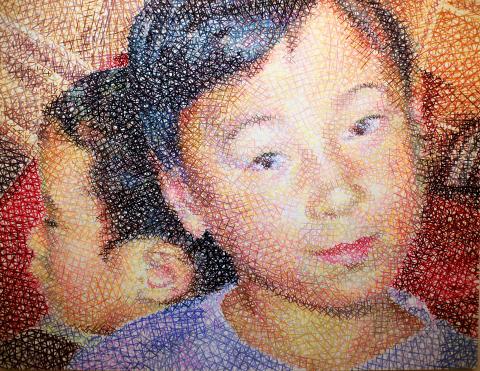

Over the past decade or so, Jeng has scaled back his palette while evolving a cross-hatching style, for which he layers the surface of the canvas with thousands of single, interconnected brush strokes of solid coloring. Blues and yellows largely disappear in favor of chartreuse, forest green and burnt sienna — the latter he emphasizes in his portraits as well.

But those earlier paintings appear too effusive — the discovery of the technique seemingly controlling Jeng, rather than being controlled by him. He was like a child who has discovered the taste of chocolate and proceeds to gorge on everything in the sweetshop. Laurence (2006 to 2008), a portrait of a woman, for example, suffers from this kind of exuberance. There is a distracting muddle of shading around the right side of the subject’s nose that essentially eliminates its outline. The gradations of color around the left cheek make the woman look as though she is wearing the half-face mask from Phantom of the Opera. It just seems slightly unbalanced — which, on second thought, might have been his purpose.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

Regardless, with Day In, Day Out, he has gained greater control over shading, while expanding his color scheme in some paintings, and limiting it in others. No brushstroke is wasted; no shadow seems out of place. Indeed, Jeng seems to be using fewer brushstrokes and achieving an even greater effect.

Take Louise for example. Jeng’s use of rich coloring immediately draws us towards the paintings’ surface — an effect muted in the earlier paintings by the use of browns and greens. Up close, we ponder the delicate yellows and blues, tinged here and there with pinks and reds. As we pull back, we come to appreciate the plasticity of painting as it gradually unfolds its harmonious realism.

In others, such as Garcon and On (Sacha), blacks and grays replace color. But even here, a wisp of yellow or a strand of peacock blue allows for a degree of complexity and warmth. Jeng’s subject matter — mostly children on their own turfs or still lifes of kitchen pots and pans — is ideally suited to his technique.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

There are also a few landscape paintings and some sketches on display that hark back to Jeng’s earlier work. But it’s the artist’s works created over the past four years that impress the most.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,