Peru’s civil war is over but fighters from the Shining Path rebel group have joined the country’s cocaine trade, turning a lawless bundle of valleys into a security problem for President Alan Garcia.

A civil war killed around 70,000 people in the 1980s and 1990s when Shining Path’s Maoist guerrillas nearly toppled the Peruvian state and both sides committed rights atrocities.

The rebels mostly disbanded after the capture of their leader, Abimael Guzman, yet violence is escalating again in the rugged and volatile Ene and Apurimac River Valleys, known as the VRAE, in Peru’s southern jungle.

It has become the most densely planted coca-growing belt in the world, according to the UN, and police say much of the cocaine leaving these fertile valleys is exported with help from a remnant band of Shining Path fighters.

Garcia, whose first term as president in the 1980s was haunted by the rise of the insurgency, has mobilized the army to try to eliminate one of Shining Path’s last footholds and prevent its influence from spreading again.

So far, the military push has been marred by setbacks. Rebels working with cocaine smuggling gangs have killed 40 poorly equipped soldiers and police over the last year in the VRAE and shot down helicopters.

The army has suffered embarrassing ambushes, traffickers buy lenient treatment from judges and mayors in local towns defend growers of coca, the leaf used to make cocaine.

Garcia is unpopular in a region that has long felt ignored by the governing elites 650km away in Lima, the capital, on the other side of the Andes.

“Alan Garcia has never come here like a man and kept his word,” said Doris Medina, 33, whose father was murdered by rebels at the height of the war.

“He has turned his back on the VRAE again,” she says while walking through the small farm where her mother plants coca, the main ingredient for cocaine, as well as coffee.

Medina’s father belonged to one of the peasant patrols that former president Alberto Fujimori set up in the 1990s to help a weak army stop the insurgents.

Medina credits Fujimori, who was later convicted of human rights crimes, for capturing Guzman and other Shining Path leaders, but holdouts from the war are still on the loose.

Colonel Elmer Mendoza of Peru’s counter-terrorism police said that as the army tries to round up 300 to 600 rebels in the VRAE, its hands have been tied by human rights protections passed after Fujimori left office to limit the use of deadly force.

Small farmers here say the government has demonized them.

“We aren’t terrorists or traffickers. We are farmers. I fought against the terrorists,” Maria Palomino, 59, whose husband was in a peasant patrol and was killed by insurgents, said while chatting in her first language of Quechua with farm hands picking coca on her daughter’s plot.

Widespread poverty and a history of underinvestment by the government in roads, education and healthcare mean that coca has long been a fallback for people like Medina and Palomino.

It grows quickly, can be harvested four times a year, and functions as a kind of parallel currency, used to pay farm hands or augment income between coffee and cacao harvests.

“Coca is our petty cash,” said Medina.

Although some of the coca is chewed as a mild stimulant or brewed for tea, as it has been for centuries, experts say up to 90 percent of it winds up being refined into cocaine.

The UN and private aid groups are trying to untangle the culture of coca and violence in this region by working with small farmers to plant alternative crops, but people tend to keep a hand in coca even after they move into the legitimate economy.

Medina is the quality control inspector at the CACVRA agricultural cooperative, which exports organic coffee and cacao raised by its 2,000 members to the US and Europe. Palomino’s daughter works for a company that exports cacao. Her grandchildren are going to university.

Medina encourages farmers to increase their incomes by improving the quality of their beans and marketing the coffee as organic, fair-trade, high-altitude, or grown by women. Yet, like a fifth of the farmers in her cooperative, her mother still plants coca to make ends meet.

Coca also distorts the local farm economy. Planters complain that during harvests farm hands charge double or triple the normal daily wage to pick coffee because they can make so much more working coca.

“The increases in labor prices have been severe, and the only way to respond is to sell higher-value coffee,” said Illich Nicolas Gavilan, who manages the cooperative. “The issue of coca is incredibly complex.”

To enter the VRAE, you must bounce along a dirt road for four hours, snaking around hairpin turns that lurch precariously over steep gorges blanketed by rain forest.

Along the way, shotgun-toting peasant patrols stop cars to charge a toll and anti-drug police search vehicles and jot down the names of everybody going into the area. It is about six hours by car from the city of Huamanga, the Shining Path’s birthplace.

The VRAE runs across four of Peru’s provinces, a cause of administrative headaches as the government tries to implement a security, development and anti-drug strategy. And the efforts are hurt by some public officials in the pay of traffickers.

“I have to be sincere, the corruption that exists in this area at some point affects everything,” said Luis Guevara Ortega, an appointee who represents Garcia’s office in the Sivia district of the VRAE.

Critics say the government has bitten off more than it can chew in the VRAE, and members of peasant patrols on the front line say there is no incentive to really go after the Shining Path.

“If Garcia guaranteed us life insurance policies for our families, we could go in and wipe out the Shining Path in two months, but why are we going to risk our lives for nothing?” said Reinaldo Silva, a patrol leader in the town of Pichari.

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

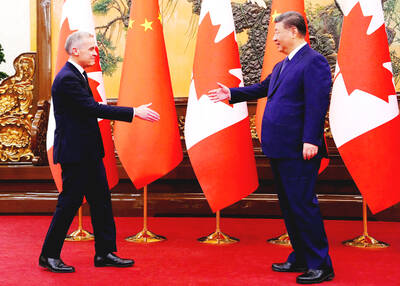

Britain’s Keir Starmer is the latest Western leader to thaw trade ties with China in a shift analysts say is driven by US tariff pressure and unease over US President Donald Trump’s volatile policy playbook. The prime minister’s Beijing visit this week to promote “pragmatic” co-operation comes on the heels of advances from the leaders of Canada, Ireland, France and Finland. Most were making the trip for the first time in years to refresh their partnership with the world’s second-largest economy. “There is a veritable race among European heads of government to meet with (Chinese leader) Xi Jinping (習近平),” said Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, director