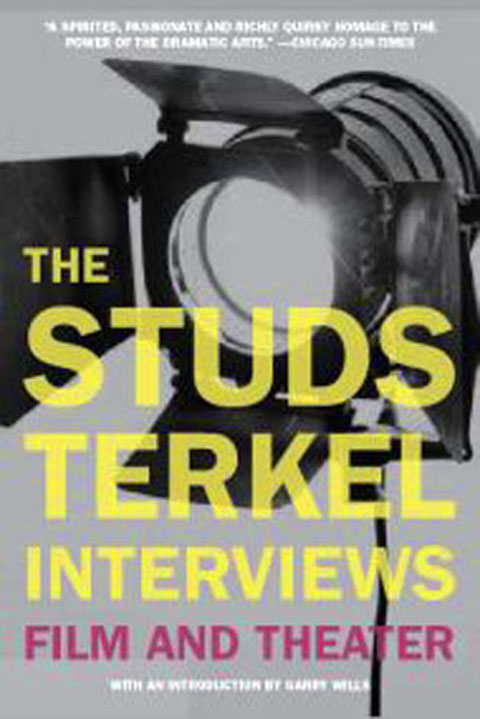

It can be hard to remember a time before pop and soccer celebrity, a time when an interview with someone famous wasn’t simply an opportunity to reveal reconstructive surgery on their septum or pose with newborn adopted babies from sub-Saharan Africa. But Studs Terkel belongs to a gentler age, an era when interviewers said things like: “What a tour de force that was. How did you carry that off?” and graciously kept quiet while their subjects rambled on about the creative subtleties of their art.

In his new collection of film and theater interviews, Terkel is so terribly polite, so scrupulously respectful, that I imagine he’s the kind of man who apologizes when he misses a shot at tennis. His opening gambit to actress Carol Channing when he meets her in 1959 is: “You have a sparkle and intelligence ...” She does not demur.

This old-fashioned gentility has served Terkel well. At 96, he is America’s preeminent oral historian, a man who has devoted his life to getting people to tell their stories. But his greatest strength is in conveying the experience of ordinary people, in getting them to elucidate the everyday grind of survival. His 1970 book, Hard Times, is deemed by many to be the quintessential oral history of the Great Depression. He has recorded interviews about work, war and race. In 1985, he won the Pulitzer Prize.

Terkel’s interview technique is self-deprecating and subtle — he removes himself from the foreground in order to allow his subject space to breathe. Reading a classic Terkel interview is a bit like looking at a pointillist painting: close up, it is merely a conglomeration of dots, but taken as a whole, a more arresting and cohesive picture forms itself. In his recent memoir, Touch and Go, Terkel attributes his success “[to] having celebrated the lives of the uncelebrated.”

The trouble with interviewing famous actors or directors is that they are already celebrated and, if allowed to, can wallow in pretension like hippos in pools of mud. While Terkel’s decision to let his interviewees speak for themselves (and never ask about their private lives) is an admirable one, the results in this collection can be hit and miss. Occasionally, as with the insufferably pompous Marlon Brando, it pays spectacular dividends. “Perhaps it is out of respect for what it means to be an artist that I do not call myself one,” says Brando, unaware that Terkel has handed him a long spool of rope with which to hang himself.

But it is a less fruitful technique when discussing the intricacies of a chorus-line folk dance in Oklahoma — unless, of course, you’re particularly enthused by that sort of thing.

When he hits his stride, however, Terkel elicits some fascinating insights into some of the greatest names of stage and screen, among them Tennessee Williams, Marcel Marceau, Ian McKellen and, um, Arnold Schwarzenegger. “When I was a small boy,” recalls the future governor of California, “my dream was not to be big physically, but big in a way that everybody listens to me when I talk, that I’m a very important person, that people recognize me and see me as something special. I had a big need for being singled out.”

The most perceptive and interesting passages come when Terkel is firmly on home ground. An extraordinary chapter deals with the varied audience reaction to some of the first performances of Waiting for Godot. When Alan Schneider directed the play in Miami, half of the well-heeled, white audience walked out. But when it was staged by a company of African-American actors in small Southern towns at the height of the civil-rights movement, the predominantly black audience felt an immediate and natural empathy for Beckett’s tramps. “Our audience knew a great deal about waiting,” recalls Gilbert Moses, the then director of Free Southern Theater. “They had been waiting all their lives [...] When Gogo takes off his shoe — a simple thing — and complains about its being too tight, the laughter of recognition bursts forth.”

April 28 to May 4 During the Japanese colonial era, a city’s “first” high school typically served Japanese students, while Taiwanese attended the “second” high school. Only in Taichung was this reversed. That’s because when Taichung First High School opened its doors on May 1, 1915 to serve Taiwanese students who were previously barred from secondary education, it was the only high school in town. Former principal Hideo Azukisawa threatened to quit when the government in 1922 attempted to transfer the “first” designation to a new local high school for Japanese students, leading to this unusual situation. Prior to the Taichung First

The Ministry of Education last month proposed a nationwide ban on mobile devices in schools, aiming to curb concerns over student phone addiction. Under the revised regulation, which will take effect in August, teachers and schools will be required to collect mobile devices — including phones, laptops and wearables devices — for safekeeping during school hours, unless they are being used for educational purposes. For Chang Fong-ching (張鳳琴), the ban will have a positive impact. “It’s a good move,” says the professor in the department of

On April 17, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) launched a bold campaign to revive and revitalize the KMT base by calling for an impromptu rally at the Taipei prosecutor’s offices to protest recent arrests of KMT recall campaigners over allegations of forgery and fraud involving signatures of dead voters. The protest had no time to apply for permits and was illegal, but that played into the sense of opposition grievance at alleged weaponization of the judiciary by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to “annihilate” the opposition parties. Blamed for faltering recall campaigns and faced with a KMT chair

Article 2 of the Additional Articles of the Constitution of the Republic of China (中華民國憲法增修條文) stipulates that upon a vote of no confidence in the premier, the president can dissolve the legislature within 10 days. If the legislature is dissolved, a new legislative election must be held within 60 days, and the legislators’ terms will then be reckoned from that election. Two weeks ago Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) proposed that the legislature hold a vote of no confidence in the premier and dare the president to dissolve the legislature. The legislature is currently controlled