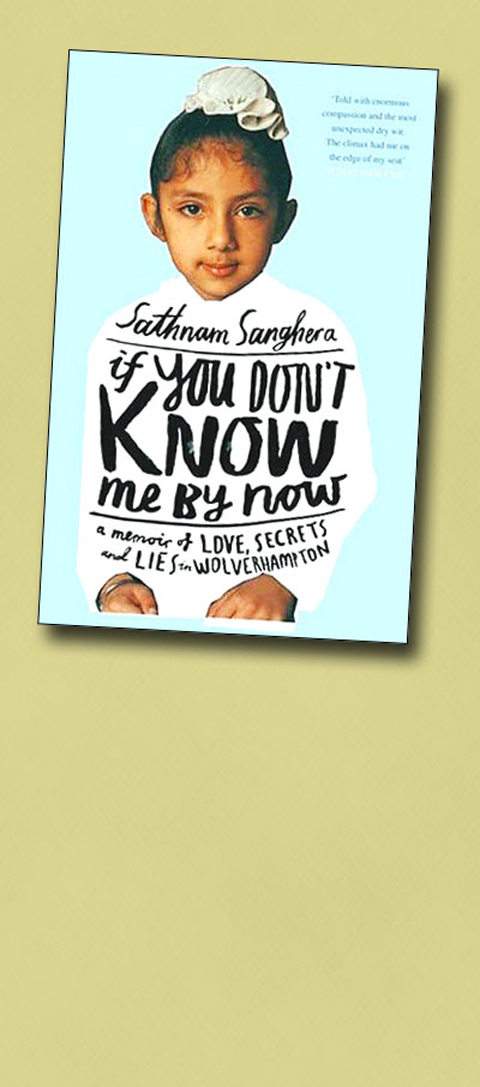

When a writer decides to use up what W. H. Auden described as “capital” — the stuff of life — in a memoir, it is a calculated sacrifice: a loss of privacy in favor of publication. Sathnam Sanghera goes further still. His memoir does not depend on passive reminiscence. It is an absorbing, ongoing drama, played out on the page. Right at the start, he tells us what he has in mind: he is nerving himself to write a letter to his Sikh mother (she speaks no English), which he will pay to have translated (he cannot write in Punjabi). He does not know what her reply will be. But he fears the letter will break her heart.

Its contents, on the face of it, are simple enough: Sanghera cannot consent to an arranged marriage. His mother wants him to marry a nice Sikh girl. He wants to be free to marry as he pleases. When out with English girlfriends, he behaves like a guilty man. Late one night, a distant aunt phones to convict him — he has been spotted with the wrong sort of girl. His mother has been informed. He barely knows the aunt in question and comically describes the call’s peculiarly traumatic effect: “My calves began to perspire, something I’d never experienced before.” You are left in no doubt about how much he needs his mother’s approval. “You see, when it comes down to it, death is a more appetizing prospect than crossing my mother.”

His education has taken him out of one world and into another. He went to Cambridge (where he got a first in English) and became a journalist (on the Financial Times before moving to the Times). In many ways, he has left his family life in Wolverhampton behind. But as a writer he knows how to exist in two places at once. He brings London back to Wolverhampton and is able to use the distance between his two worlds to entertaining effect. I loved the description of his mother’s superstitious welcome of him involving birdseed and a red chili pepper. I also relished the description (his writing is full of gentle, hyperbolic wit) of his mother’s monologues as “ocean liners” because they “require time to change direction.” He smiles affectionately in her direction but laughs, often unkindly, at himself.

It is while he is trying to help reduce the weight of his mother’s grossly overstuffed suitcase — she is preparing for a trip to India — that he finds an item heavier than all the rest. Along with miscellaneous pills is a letter marked: “To whom it may concern” in which he discovers that his father and his sister have schizophrenia. He is 24 and his mother has protected him from the truth all his life.

At one point, he says: “We never look at our parents closely, do we, just as we don’t see them as people.” The book attempts to correct that. It contains the beautifully reconstituted story of his mother’s arranged marriage and its painful aftermath. And he works hard at trying to understand his father and his sister and their suffering. As he reads up about the disease, he monitors his own reactions with dismay: “My father and sister had gone from being my father and sister, two people who behaved a little strangely at times, but two people I loved, to being a collection of symptoms.”

But it is the letter that we are waiting to have answered. It creates and sustains the suspense that has had you hooked throughout. The book could not be more enjoyable, engaging or moving. But I was left feeling uneasy about its private purpose. For the memoir has been used as a tool to influence his mother’s reply, nudge her in the right direction and to protect himself. She is, after all, told that her answer — to his most private question — will be published in his book.

April 28 to May 4 During the Japanese colonial era, a city’s “first” high school typically served Japanese students, while Taiwanese attended the “second” high school. Only in Taichung was this reversed. That’s because when Taichung First High School opened its doors on May 1, 1915 to serve Taiwanese students who were previously barred from secondary education, it was the only high school in town. Former principal Hideo Azukisawa threatened to quit when the government in 1922 attempted to transfer the “first” designation to a new local high school for Japanese students, leading to this unusual situation. Prior to the Taichung First

The Ministry of Education last month proposed a nationwide ban on mobile devices in schools, aiming to curb concerns over student phone addiction. Under the revised regulation, which will take effect in August, teachers and schools will be required to collect mobile devices — including phones, laptops and wearables devices — for safekeeping during school hours, unless they are being used for educational purposes. For Chang Fong-ching (張鳳琴), the ban will have a positive impact. “It’s a good move,” says the professor in the department of

On April 17, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) launched a bold campaign to revive and revitalize the KMT base by calling for an impromptu rally at the Taipei prosecutor’s offices to protest recent arrests of KMT recall campaigners over allegations of forgery and fraud involving signatures of dead voters. The protest had no time to apply for permits and was illegal, but that played into the sense of opposition grievance at alleged weaponization of the judiciary by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to “annihilate” the opposition parties. Blamed for faltering recall campaigns and faced with a KMT chair

Article 2 of the Additional Articles of the Constitution of the Republic of China (中華民國憲法增修條文) stipulates that upon a vote of no confidence in the premier, the president can dissolve the legislature within 10 days. If the legislature is dissolved, a new legislative election must be held within 60 days, and the legislators’ terms will then be reckoned from that election. Two weeks ago Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) proposed that the legislature hold a vote of no confidence in the premier and dare the president to dissolve the legislature. The legislature is currently controlled