In the 1970s the black artist Adrian Piper donned an Afro wig and a fake mustache and prowled the streets of various cities in the scowling, muttering guise of the Mythic Being, a performance-art version of a prevailing stereotype, the black male as a mugger, hustler, gangsta.

In the photographs that resulted, you can see what she was up to. In an era when some politicians and much of the popular press seemed to be stoking racial fear, she was turning fear into farce - but serious, and disturbing, farce, intended to punch a hole in pervasive fictions while acknowledging their power.

Recently a new kind of Mythic Being arrived on the scene, the very opposite of the one Piper introduced some 30 years ago. He doesn't mutter; he wears business suits; he smiles. He is by descent half black African, half white American. His name is Barack Obama.

PHOTOS: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

On the rancorous subject of the country's racial history he isn't antagonistic; he speaks of reconciliation, of laying down arms, of moving on, of closure. He is presenting himself as a 21st-century postracial leader, with a vision of a color-blind, or color-embracing, world to come.

Campaigning politicians talk solutions; artists talk problems. Politics deals in goals and initiatives; art, or at least interesting art, in a language of doubt and nuance. This has always been true when the subject is race. And when it is, art is often ahead of the political news curve, and heading in a contrary direction.

In a recent solo debut at Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery in Chelsea a young artist named Rashid Johnson created a fictional secret society of black intellectuals, a cross between Mensa and the Masons. At first uplift seemed to be the theme. The installation was framed by a sculpture resembling giant cross hairs. Or was it a microscope lens, or a telescope's? The interpretive choice was yours. So was the decision to stay or run. Here was art beyond old hot-button statements, steering clear of easy condemnations and endorsements. But are artists like Johnson making "black" art? Political art? Identity art? There are no answers, or at least no unambiguous ones.

Since Piper's Mythical Being went stalking in the 1970s - a time when black militants and blaxploitation movies reveled in racial difference - artists have steadily challenged prevailing constructs about race.

As multiculturalism entered mainstream institutions in the 1980s, the black conceptualist David Hammons stayed outdoors, selling snowballs on a downtown Manhattan sidewalk. And when, in the 1990s, Robert Colescott was selected as the first black artist to represent the US at the Venice Biennale, he brought paintings of figures with mismatched racial features and skin tones, political parables hard to parse.

At the turn of the present millennium, with the art market bubbling up and the vogue for identity politics on the wane, William Pope.L - the self-described "friendliest black artist in America" - belly-crawled his way up Broadway, the Great White Way, in a Superman outfit, and ate copies of the Wall Street Journal.

Today, as Obama pitches the hugely attractive prospect of a postracial society, artists have, as usual, already been there, surveyed the terrain and sent back skeptical, though hope-tinged, reports. And you can read those reports in art all around New York this spring, in retrospective surveys like Wack! Art and the Feminist Revolution currently at the P.S 1 Contemporary Art Center in Queens, in the up-to-the-minute sampler that is the 2008 Whitney Biennial, in gallery shows in Chelsea and beyond, and in the plethora of art fairs clinging like barnacles to the Armory Show on Pier 94 this weekend.

POSTRACIAL ART

Wack! is a good place to trace a postracial impulse in art going back decades. Piper is one of the few black artists in the show, along with Howardena Pindell and Lorraine O'Grady. All three began their careers with abstract work, at one time the form of black art most acceptable to white institutions, but went on to address race aggressively.

In a 1980 performance video, Free, White and 21, Pindell wore whiteface to deliver a scathing rebuke of art-world racism. In the same year O'Grady introduced an alter ego named Mlle Bourgeoise Noire who, dressed in a beauty-queen gown sewn from white formal gloves, crashed museum openings to protest all-white shows. A few years later Piper, who is light skinned, began to selectively distribute a printed calling card at similar social events. It read:

Dear Friend,

I am black. I am sure you did not realize this when you made/laughed at/agreed with that racist remark. In the past I have attempted to alert white people to my racial identity in advance. Unfortunately, this invariably causes them to react to me as pushy, manipulative or socially inappropriate. Therefore, my policy is to assume that white people do not make these remarks, even when they believe there are not black people present, and to distribute this card when they do.

I regret any discomfort my presence is causing you, just as I am sure you regret the discomfort your racism is causing me.

Sincerely yours,

Adrian Margaret Smith Piper

Although these artists' careers took dissimilar directions, in at least some of their work from the 1970s and 1980s they all approached race, whiteness as well as blackness, as a creative medium. Race is treated as a form of performance; an identity that could, within limits, be worn or put aside; and as a diagnostic tool to investigate social values and pathologies.

Piper's take on race as a form of creative nonfiction has had a powerful influence on two generations of black Americans who, like Obama, didn't experience the civil rights movement firsthand, and who share a cosmopolitan attitude toward race. In 2001 that attitude found corner-turning expression in Freestyle, an exhibition organized at the Studio Museum in Harlem by its director, Thelma Golden.

When Golden and her friend the artist Glenn Ligon called the 28 young American artists "postblack," it made news. It was a big moment. If she wasn't the first to use the term, she was the first to apply it to a group of artists who, she wrote, were "adamant about not being labeled 'black' artists, though their work was steeped, in fact deeply interested, in redefining complex notions of blackness."

The work ranged from mural-size images of police helicopters painted with hair pomade by Kori Newkirk, who lives in Los Angeles, to computer-assisted geometric abstract painting by the New York artist Louis Cameron. Newkirk's work came with specific if indirect ethnic references; Cameron's did not. Although "black" in the Studio Museum context, they would lose their racial associations in an ethnically neutral institution like the Museum of Modern Art.

Ethnically neutral? That's just a code-term for white, the no-color, the everything-color. For whiteness is as much - or as little - a racial category as blackness, though it is rarely acknowledged as such wherever it is the dominant, default ethnicity. Whiteness is yet another part of the postracial story. Like blackness, it has become a complicated subject for art. And few have explored it more forcefully and intimately than Nayland Blake.

Blake, 48, is the child of a black father and a white mother. In various performance pieces since the 1990s he has dressed up as a giant rabbit, partly as a reference to Br'er Rabbit of Joel Chandler Harris' Uncle Remus stories, a wily animal who speaks in Southern black dialect and who survives capture by moving fast and against expectations.

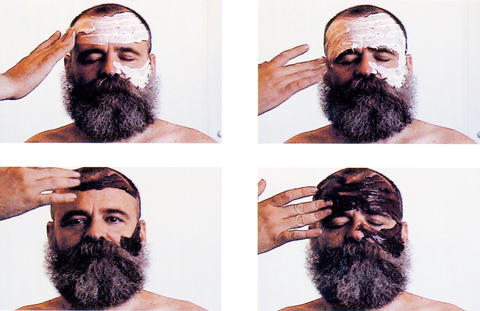

In 2001 Blake appeared in a video with another artist, AA Bronson. Each had his face slathered with cake frosting, chocolate in Blake's case, vanilla in Bronson's. When then two men exchanged a long kiss, the colors, and presumably the flavors, began to blend. Shared love, the implication was, dissolves distinctions between "black" and "white," which, as racial categories, are cosmetic, superficial.

As categories they are also explosive. In 1984, when Hammons painted a poster of the Reverend Jesse Jackson as a blond, blue-eyed Caucasian and exhibited it outdoors in Washington, the piece was trashed by a group of black men. Hammons intended the portrait, How Ya Like Me Now, as a comment on the paltry white support for Jackson's presidential bid that year. Those who attacked it assumed the image was intended as an insult to Jackson.

More recently, when Kara Walker cut out paper silhouettes of fantasy slave narratives, with characters - black and white alike - inflicting mutual violence, she attracted censure from some black artists. At least some of those objecting had personal roots in the civil rights years and an investment in art as a vehicle for racial pride, social protest and spiritual solace.

THE FICTION OF WHITENESS

Walker, whose work skirts any such overt commitments, was accused of pandering to a white art market with an appetite for images of black abjection. She was called, in effect, a sellout to her race.

In a television interview a few weeks ago, before he formed plans to deliver his speech on race, Obama defended his practice of backing off from discussion of race in his campaign. He said it was no longer a useful subject in the national dialogue; we're over it, or should be.

But in fact it can be extremely useful. There is no question that his public profile has been enhanced by his Philadelphia address, even if the political fallout in terms of votes has yet to be gauged.

The topic of race and blood has always been an inflammatory one in the US. Piper broached it in a 1988 video installation and delivered some bad news. Facing us through the camera, speaking with the soothing composure of a social worker or grief counselor, she said that, according to statistics, if we were white Americans, chances were very high that we carried at least some black blood. That was the legacy of slavery. She knew we would be upset. She was sorry. But that was the truth. The piece was titled Cornered.

And are we upset? I'll speak for myself; it's not a question. Of course not. Which is a good thing, because the concept of race in America - the fraught fictions of whiteness and blackness - is not going away soon. It is still deep in our system. Whether it is or isn't in our blood, it's in our laws, our behavior, our institutions, our sensibilities, our dreams.

It's also in our art, which, at its contrarian and ambiguous best, is always on the job, probing, resisting, questioning and traveling miles ahead down the road.

April 28 to May 4 During the Japanese colonial era, a city’s “first” high school typically served Japanese students, while Taiwanese attended the “second” high school. Only in Taichung was this reversed. That’s because when Taichung First High School opened its doors on May 1, 1915 to serve Taiwanese students who were previously barred from secondary education, it was the only high school in town. Former principal Hideo Azukisawa threatened to quit when the government in 1922 attempted to transfer the “first” designation to a new local high school for Japanese students, leading to this unusual situation. Prior to the Taichung First

The Ministry of Education last month proposed a nationwide ban on mobile devices in schools, aiming to curb concerns over student phone addiction. Under the revised regulation, which will take effect in August, teachers and schools will be required to collect mobile devices — including phones, laptops and wearables devices — for safekeeping during school hours, unless they are being used for educational purposes. For Chang Fong-ching (張鳳琴), the ban will have a positive impact. “It’s a good move,” says the professor in the department of

On April 17, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) launched a bold campaign to revive and revitalize the KMT base by calling for an impromptu rally at the Taipei prosecutor’s offices to protest recent arrests of KMT recall campaigners over allegations of forgery and fraud involving signatures of dead voters. The protest had no time to apply for permits and was illegal, but that played into the sense of opposition grievance at alleged weaponization of the judiciary by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to “annihilate” the opposition parties. Blamed for faltering recall campaigns and faced with a KMT chair

Article 2 of the Additional Articles of the Constitution of the Republic of China (中華民國憲法增修條文) stipulates that upon a vote of no confidence in the premier, the president can dissolve the legislature within 10 days. If the legislature is dissolved, a new legislative election must be held within 60 days, and the legislators’ terms will then be reckoned from that election. Two weeks ago Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) proposed that the legislature hold a vote of no confidence in the premier and dare the president to dissolve the legislature. The legislature is currently controlled