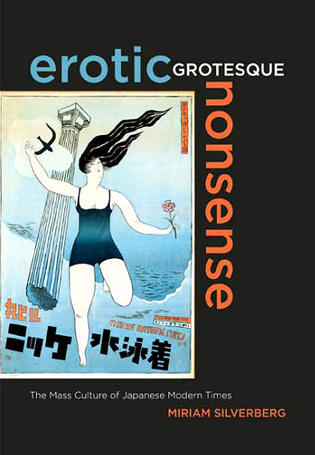

This book is mildly interesting and here and there even enjoyable, though it's nothing like as exciting as its vivid title suggests it's going to be. It's about the entertainment and fashion industries in Japan in the 1920s and 1930s, and the title is the phrase the rising militarists concocted to describe and discredit such things. Men who are in favor of wars don't like people enjoying themselves. If your job is to persuade the young to pilot planes laden with explosives into ships belonging to people with different-colored passports, you can't let them think that a recipe for a good time is dancing the night away and sipping the newly-fashionable drinks called cocktails. You might be able to convince them that a spot of beheading in Nanjing would be more enjoyable, but when trying to promote that leisure activity you'd have to discourage them in advance from any alternative ideas they might have managed to acquire.

About eight years ago I attended a press conference in Taipei at which an arms expert said that any conflict between Taiwan and China would last a day and a half, that Taiwan would lose, and about 5 million Taiwanese people would be crushed to death as missiles sliced through buildings. He went on to express the opinion that today's young didn't appear to him to be very well prepared for this kind of eventuality.

This man sounded to me like one of those military Japanese in the 1930s. He didn't like seeing the young with tinted hair and studs in their tongues because he thought these things wouldn't predispose them to fight the good fight when the time came. War and happiness seem in all historical periods to be fundamentally opposed to each other, and it isn't difficult, when you're inviting people to have their faces torn away by pieces of flying metal, to understand why happiness is usually the preferred option.

In 1930s Japan, newspaper articles on fashion and new American films, plus gossip on sexual questions relating to movie stars, did sometimes serve to deflect attention from political and military developments. The Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 was, according to this author, neglected in favor of an article on how sexual activity often moved from the cinema screen to the cinema seats. Thus popular culture, though frowned on by the increasingly militaristic authorities, could also be useful as a smokescreen to keep details of their own aggression from public scrutiny. And rather than print details of the League of Nations' Lytton Report on the invasion, the Tokyo press titillated its readers with a minute examination of the bodies of the performers in Hollywood's then-new Tarzan films, considered sensational at the time for showing a man in only a loincloth and a woman with bare legs. What was at one moment condemned as erotic, grotesque nonsense could at another be useful to hide inconvenient news.

Japanese life in the 20th century was characterized by extreme catastrophes alternating with an urgent love affair with all aspects of the modern. The two biggest catastrophes were the Great Earthquake of Sept. 1, 1923 and the bombing of Japanese cities in 1944 to 1945, culminating in the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Most of Tokyo had to be re-built both times, but it was the earthquake that in the Japanese mind marked the big break with the traditional, making way for the arrival of the modern.

The term "modern" included department stores, provocative dress styles, smoking in public, cocktails, the financial independence (and perceived promiscuity) of women, photography, cinema, radio, mass-circulation newspapers and the influence of advertising, together with the arrival of a whole range of electronic household devices. Tradition, by contrast, was associated with social deference, religion, sexual modesty and hostility to Western innovations.

Erotic Grotesque Nonsense parallels Frank Dikotter's survey of the arrival of modern objects in early 20th century China in Things Modern [reviewed in the Taipei Times on Aug. 12, 2007]. Like him, Miriam Silverberg thinks of herself as "revisionist," meaning that she doesn't deplore the developments she describes as the incursions of an exploitative capitalism, but sees them as things welcomed by the population at large.

Hollywood films, in her view, were central to the Japanese idea of the modern during the 1930s. These, however, sometimes contained visions of the "exotic" Orient that included sexual invitation on the one hand and so-called Asiatic barbarism on the other. This was retained in doctored Japanese versions, but with Japan firmly installed on the "civilized" side, and the alluring, but nevertheless degenerate, habits reserved for the rest of Asia, notably China.

With the beginning of the Japanese invasions - first of China, then of Southeast Asia - erotic grotesque nonsense wasn't entirely sidelined, but was, at least initially, incorporated into the military's program. Comparisons were made between the female body and a battlefield - between male pleasure and male death, in other words. This clearly wasn't going to deceive many people for very long, and soon patriotic Japanese films openly glorified war and "self-sacrifice" for the greater good of the fatherland.

Erotic Grotesque Nonsense is an academic book, and so not easygoing for the general reader. This is a pity. A hundred years ago someone might have said that an Oxford professor called A.C. Bradley had written a wonderful book called Shakespearean Tragedy and that the average educated person might well enjoy it. Sadly, this is no longer the case, and "academic" now generally carries the implication "unlikely to give any real pleasure." Though this book generally avoids, for instance, post-structuralist jargon, its catchy title nonetheless remains its most alluring feature.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Snoop Dogg arrived at Intuit Dome hours before tipoff, long before most fans filled the arena and even before some players. Dressed in a gray suit and black turtleneck, a diamond-encrusted Peacock pendant resting on his chest and purple Chuck Taylor sneakers with gold laces nodding to his lifelong Los Angeles Lakers allegiance, Snoop didn’t rush. He didn’t posture. He waited for his moment to shine as an NBA analyst alongside Reggie Miller and Terry Gannon for Peacock’s recent Golden State Warriors at Los Angeles Clippers broadcast during the second half. With an AP reporter trailing him through the arena for an