For decades, I assumed I needed to sleep just five to six hours a night. I nearly always awoke before the alarm in the morning. But I also nearly always fell asleep at concerts and plays, on the subway or while reading or riding in a car.

Last summer, when I was able to operate completely on my body's own time clock, I discovered that it preferred seven to seven and a half hours of sleep. I also discovered that when I slept at night for however long my body wanted to, my daytime dozes all but disappeared.

Surveys have shown that few of us past infancy and toddlerhood are receiving the amount of sleep our bodies and brains need to restore them to full function for the day ahead. And many of us - children, teenagers and adults of all ages - may pay a hefty price.

ILLUSTRATION: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Crucial brain functions occur in sleep that cannot be reproduced when we are awake. But more than intellectual prowess can suffer; though definitive data are still lacking, a chronic shortage of sleep has been linked to serious physical ills, including heart disease, diabetes and obesity.

From infancy to adulthood, there are marked changes in how much sleep people need each day, the amount of time spent in each stage of sleep and how easily they fall asleep and stay asleep, a factor scientists call sleep efficiency.

Newborns sleep 16 to 18 hours a day, though rarely more than 4 hours at a time. By about three months, the time pediatrician Richard Ferber, Director of the Center for Pediatric Sleep Disorders at Children's Hospital Boston, suggests parents should try to enforce a more reasonable sleep schedule, babies' sleep patterns begin to respond to circadian rhythms of day and night. Year-old infants typically sleep 10 to 12 hours a night and nap 3 to 5 hours during the day.

The amount of sleep children need decreases gradually with age; preschoolers need 10 to 12 hours. By age 6, a tendency to be a lark or a night owl emerges, the latter often leading to havoc on school days, when children have to be awakened earlier than their body clocks dictate.

Sleep deprivation seems to start early. A 2004 survey by the National Sleep Foundation found that on average, children in every age group from infancy through fifth grade failed to get even the low end of the recommended range of sleep.

The real agony emerges in adolescence. As children go through puberty, two things happen to make getting enough sleep problematic: They need more sleep than prepubescent children, not less - 9 to 10 hours a night - and their body clocks shift to a later time to fall asleep and, consequently, a later awakening.

Amy Wolfson, a psychologist at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, and Mary Carskadon, a sleep researcher at the Brown University School of Medicine in Providence, Rhode Island, have found that few adolescents sleep the amount they need. The average eighth-grader sleeps less than eight hours, and more than a quarter of high school and college students are chronically sleep deprived, they reported.

In a report last February in the journal Pediatrics, researchers from the Columbia University School of Nursing estimated that "15 million American children are affected by inadequate sleep." They based this on the findings of a national health survey in 2003 of 68,418 children ages 6 to 17. In the study, the percentage of children who failed to sleep enough rose with age and increased markedly among children 12 and older.

Sleep deprivation has been linked to poorer grades, moodiness and depression. Though you may question which comes first, Avi Sadeh, a psychologist at Tel Aviv University, studied the effects of adding or subtracting an hour of sleep on 77 children in the fourth and sixth grades. Those deprived of an hour's sleep performed less well on tests for reaction time, recall and responsiveness than the children who slept the extra hour.

Insufficient sleep in the teenage years has been associated with increased risks of disciplinary problems, sleepiness in class and poor concentration, not to mention traffic accidents.

With televisions and computers in their rooms, many teenagers cannot resist the temptation to stay up late, especially because their bodies do not begin to produce the sleep hormone melatonin until 1am, as opposed to 10pm in most adults.

Then there is the problem of school starting times. Many teenagers have to leave for school before 7am to be in class by 7:30am.

A study of more than 7,000 high school students in Minnesota showed that when some schools switched their starting time to 8:40am from 7:15am, students had more sleep on school nights, were less sleepy during the day, earned slightly higher grades and experienced fewer depressive feelings and behaviors than students in schools that kept early starting times.

By contrast, Carskadon wrote, in a school that switched its starting time to 7:20am from 8:25am, nearly half the students were "pathologically sleepy" at 8:30am. "These early school start times are abusive," she wrote.

Ronald Dahl, a sleep expert at the University of Pittsburgh, says sleep deprivation among teenagers creates a "negative spiral" of fatigue, emotional instability, poor decision-making and risky behavior. Dahl and others agree that long-term studies of the effects of sleep deprivation in the teenage years are desperately needed.

Harmful effects on adult health have been associated with sleeping too little and with sleeping too much, though what constitutes too little and too much varies from study to study. Studies suggest that adults who sleep seven to eight hours a night are the healthiest. About a third fall into that range. More than a third sleep less than seven hours, and nearly a third sleep more than eight hours.

A six-year study of more than 1 million adults ages 30 to 102 by researchers at the University of California, San Diego, and the American Cancer Society found the highest mortality rate among those who slept less than four hours or more than eight hours a night. The study took into account factors like age, diet and exercise and risk factors like smoking. The lowest death rates were found among those who averaged six to seven hours of sleep.

Although the lead researcher, Daniel Kripke, now an emeritus professor, could not explain the findings, studies have found that people who sleep the least or the most are more likely to have high blood pressure, symptoms of depression or heart disease. Sleep deprivation can also inhibit the body's ability to produce insulin and increases the risk of diabetes.

In the Nurses' Health Study, Najib Ayas, then at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, found that among 71,617 women followed for 10 years, long and short sleepers both faced increased risk of heart disease. Ayas, now at Vancouver General Hospital, reported that women who slept eight hours a night had the lowest risk.

In another finding among the nurses, those who slept nine or more hours a night were twice as likely to develop Parkinson's disease as those who averaged six hours or less. This study, by scientists at the National Institutes of Health, tracked 80,000 nurses, all initially free of the disease, for 24 years.

Though it seems counterintuitive, people who sleep less tend to weigh more. After adjusting the data for all sorts of potentially confounding factors, researchers who studied 990 employed adults in rural Iowa found that the less sleep they received on weeknights, the higher their body mass index.

Shahrad Taheri of the University of Bristol in England noted that in a long-term UK study, "short sleep duration at an early age of 30 months predicts obesity at age 7." Taheri suggested last year in The Archives of Disease in Childhood that sleep loss in toddlers might change brain mechanisms that regulate appetite and energy expenditure.

In the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study, short sleep duration was associated with low levels of leptin, a hormone that signals the need for more calories. In addition, short sleepers had higher levels of the hormone ghrelin, which is released mainly in the stomach at highest levels before meals and has been shown to increase food intake.

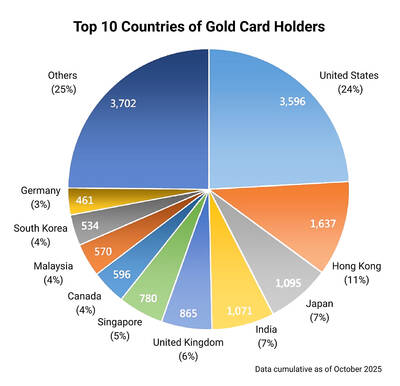

Seven hundred job applications. One interview. Marco Mascaro arrived in Taiwan last year with a PhD in engineering physics and years of experience at a European research center. He thought his Gold Card would guarantee him a foothold in Taiwan’s job market. “It’s marketed as if Taiwan really needs you,” the 33-year-old Italian says. “The reality is that companies here don’t really need us.” The Employment Gold Card was designed to fix Taiwan’s labor shortage by offering foreign professionals a combined resident visa and open work permit valid for three years. But for many, like Mascaro, the welcome mat ends at the door. A

The Western media once again enthusiastically forwarded Beijing’s talking points on Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s comment two weeks ago that an attack by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on Taiwan was an existential threat to Japan and would trigger Japanese military intervention in defense of Taiwan. The predictable reach for clickbait meant that a string of teachable moments was lost, “like tears in the rain.” Again. The Economist led the way, assigning the blame to the victim. “Takaichi Sanae was bound to rile China sooner rather than later,” the magazine asserted. It then explained: “Japan’s new prime minister is

NOV. 24 to NOV. 30 It wasn’t famine, disaster or war that drove the people of Soansai to flee their homeland, but a blanket-stealing demon. At least that’s how Poan Yu-pie (潘有秘), a resident of the Indigenous settlement of Kipatauw in what is today Taipei’s Beitou District (北投), told it to Japanese anthropologist Kanori Ino in 1897. Unable to sleep out of fear, the villagers built a raft large enough to fit everyone and set sail. They drifted for days before arriving at what is now Shenao Port (深奧) on Taiwan’s north coast,

Divadlo feels like your warm neighborhood slice of home — even if you’ve only ever spent a few days in Prague, like myself. A projector is screening retro animations by Czech director Karel Zeman, the shelves are lined with books and vinyl, and the owner will sit with you to share stories over a glass of pear brandy. The food is also fantastic, not just a new cultural experience but filled with nostalgia, recipes from home and laden with soul-warming carbs, perfect as the weather turns chilly. A Prague native, Kaio Picha has been in Taipei for 13 years and