Is the bell tolling for the recorded music industry? Some commentators are saying as much following a decision by UK band Radiohead to release their next album from their Web site, cutting out the record labels.

Even more revolutionary, the group is asking fans to decide how much to pay for In Rainbows, available for download from Wednesday. A spokesman for Radiohead says: "As you might imagine, offers are ranging from nothing to more than you might pay for a CD in the shops."

In part, Radiohead are asking: how much do you value us? But implicitly, they are also questioning how much people are prepared to pay to download music over the Internet. It's a question that music companies have been grappling with ever since the file-sharing site Napster was closed in 2001.

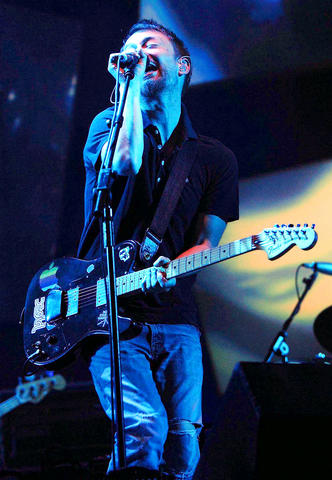

PHOTO: AP

Once again, the economics of the music industry is being turned on its head as artists take matters into their own hands. Haven't we already seen Prince sell 3 million copies of his new album via a deal with UK newspaper the Mail on Sunday during the summer? Lily Allen, Arctic Monkeys and countless others have launched themselves via e-mail or social networking sites such as MySpace.

For its part, the public has been ripping the industry's conventional business model to shreds by illegally downloading music for years. Internet piracy and the switch to digital sales are costing the music majors millions: Profits from EMI's music division plunged by US$200 million in the 12 months to March 2007.

IFPI, the trade body that represents the music companies, has estimated that the global traffic of illegal CDs is worth US$500 billion. About 20 billion songs were illegally downloaded or swapped worldwide last year. The organization also reckons that more than one in three CDs is pirated.

But it's one thing to conclude that the music companies are in trouble, quite another to conclude that they will shortly be consigned to the dustbin of history. Mark Mulligan of Jupiter Research points out that Prince is using BMG/Sony to distribute his new album in Europe, but not in the UK, where the Mail was deemed to have done the job for him. Lily Allen and the Arctic Monkeys, after their Internet launches, have signed to EMI and Domino Records respectively.

But it's not a zero sum game. Radiohead's new album will still be launched conventionally next year. The group is talking to a number of labels. Chris Hufford, Radiohead's manager, says the Web site launch is just "another way of doing things."

But Chris Parry, founder of Fiction records, says that the industry is undergoing a seismic shift. "The music companies used to have a monopoly when it came to finding new talent and distributing songs. Now artists such as Radiohead are beginning to challenge the status quo. New technology has subverted the way the majors used to do business. The balance of power has shifted from the companies to the fans and artists."

Not everyone is comfortable with the power of the majors. A few years ago, Mick Hucknall of Simply Red said that Internet piracy was justifiably the record companies' problem, as major labels had ripped off artists for decades. Simply Red, once signed to Warner Music, has started its own label: simplyred.com. Hucknall complains that artists have to pay record companies for the costs of their recordings and their marketing, but the majors end up owning the master tapes. He says: "Major record companies must reform. They have got too big for their boots. I think artists will break away from record companies. I don't think artists will sign to major companies unless they own their masters."

Clearly, the Internet offers the opportunity for artists to sideline the companies, but to date this hasn't happened on a large scale, although Radiohead and Simply Red have shown what can be done.

Paul Lewis, acting editor of Music Week, says: "It's hard to visualize where it's going to end. But the business is going through changes other than those brought about by the Internet. Music is not as mass-audience as it once was - there are lots of other things competing for people's time: computer games, social networking, mobile phones. That is why some companies are dropping the word music altogether and calling themselves entertainment groups."

The rights to live concerts, merchandising and broadcasting are increasingly a part of deals between companies and artists as the majors seek alternative revenue streams to offset a steep decline in CD sales. A different sort of contract was established in 2002 when Robbie Williams set up a joint venture with EMI that saw the company take a 25 percent stake and a share of profits from DVD sales, touring and other initiatives, as well as music sales.

Analysts say that a hybrid system of music distribution is emerging, one that is becoming increasingly innovative. Two weeks ago, a scheme began in the US that allows iPod owners to download songs they hear over the speakers at Starbucks coffee houses directly on to their device. The price? Just 99 cents.

The music companies know they have to adapt, like other industries, if they are to survive in the digital world, where the cost of selling online is essentially zero. But how they do it, profitably, is by no means clear.

Seven hundred job applications. One interview. Marco Mascaro arrived in Taiwan last year with a PhD in engineering physics and years of experience at a European research center. He thought his Gold Card would guarantee him a foothold in Taiwan’s job market. “It’s marketed as if Taiwan really needs you,” the 33-year-old Italian says. “The reality is that companies here don’t really need us.” The Employment Gold Card was designed to fix Taiwan’s labor shortage by offering foreign professionals a combined resident visa and open work permit valid for three years. But for many, like Mascaro, the welcome mat ends at the door. A

Last week gave us the droll little comedy of People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) consul general in Osaka posting a threat on X in response to Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi saying to the Diet that a Chinese attack on Taiwan may be an “existential threat” to Japan. That would allow Japanese Self Defence Forces to respond militarily. The PRC representative then said that if a “filthy neck sticks itself in uninvited, we will cut it off without a moment’s hesitation. Are you prepared for that?” This was widely, and probably deliberately, construed as a threat to behead Takaichi, though it

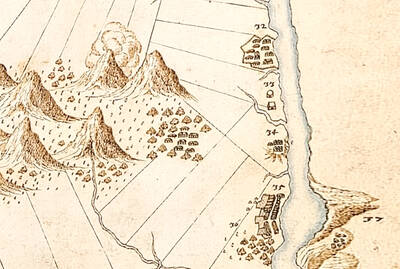

Nov. 17 to Nov. 23 When Kanori Ino surveyed Taipei’s Indigenous settlements in 1896, he found a culture that was fading. Although there was still a “clear line of distinction” between the Ketagalan people and the neighboring Han settlers that had been arriving over the previous 200 years, the former had largely adopted the customs and language of the latter. “Fortunately, some elders still remember their past customs and language. But if we do not hurry and record them now, future researchers will have nothing left but to weep amid the ruins of Indigenous settlements,” he wrote in the Journal of

If China attacks, will Taiwanese be willing to fight? Analysts of certain types obsess over questions like this, especially military analysts and those with an ax to grind as to whether Taiwan is worth defending, or should be cut loose to appease Beijing. Fellow columnist Michael Turton in “Notes from Central Taiwan: Willing to fight for the homeland” (Nov. 6, page 12) provides a superb analysis of this topic, how it is used and manipulated to political ends and what the underlying data shows. The problem is that most analysis is centered around polling data, which as Turton observes, “many of these