Taipei Times: Why did you participate in this project?

Chang Ta-chun: I have been following Beijing opera for many years. ... I have been working as a creative artist for many years, but always as a lone creator. Many of my works have been adapted for TV, and I have participated in some productions, but ultimately, these were my works. But in joining in this project, I knew I had come to learn. And unless you are actively creating something, you cannot learn anything.

TT: Is this your own version of Water Margin?

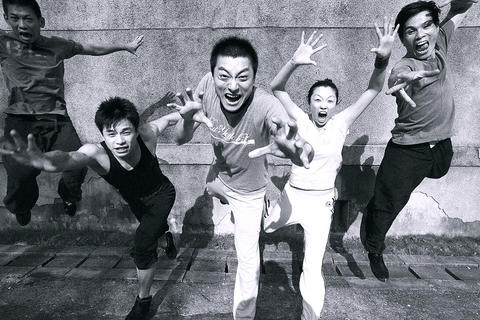

PHOTOS: TAIPEI TIMES AND COURTESY OF CONTEMPORARY LEGEND THEATER

CTC: The folk stories of China have a unique tradition. Novels like Water Margin and The Three Kingdoms (三國演義) have been pulled together from shorter stories that were already transmitted among the people. Vernacular tales have always had people adding bits, editing bits, everyone sharing material ... the stories belonged to everyone. There was never a problem about royalties. Everyone is free to make changes, because the story (as it exists today) has evolved through a process of changes. The story changes constantly with changing times ... so if there is anything about the story that I am dissatisfied with, then I am free to change it. I have never been that satisfied with Water Margin as a novel. Even in its various operatic forms, I have not always been satisfied. So I have added something of my own.

TT: Does the language of Chinese opera pose too high a barrier for young audiences today?

CTC: Everything Wu Hsing-kuo is doing is bringing in young audiences. As for difficulties with language (the language of classical Chinese opera), I was taken to the opera from around age four. The gap in understanding for me then was much greater than for a 20-something today. By taking in an opera once every two or three weeks, I learned to understand, even without the aid of subtitles. ... We don't have to dumb opera down for young people, nor do we need to go too far out of our way to cater to them.

TT: What is the relevance of Water Margin to a modern audience?

CTC: The bandits of the story have their own conception of justice. And the priority of this justice is higher than that of officials in the government, though it is below that of the emperor, who represents god, or heaven. The question that 108 Heroes addresses, is about a group of men, each with their own reason for not fitting into society. They may be discontented with mainstream society. ... They have been forced out of society, so they must create their own society. Then they need to find a way of making this created society fit in with the mainstream or use it to change the mainstream.

The first half of the show is about men trying to overturn a mainstream society about which they are dissatisfied. The second half is about women trying to overturn a masculine (social order) about which they are dissatisfied.

PHOTO: TAIPEI TIMES FILE PHOTO

Exceptions to the rule are sometimes revealing. For a brief few years, there was an emerging ideological split between the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) that appeared to be pushing the DPP in a direction that would be considered more liberal, and the KMT more conservative. In the previous column, “The KMT-DPP’s bureaucrat-led developmental state” (Dec. 11, page 12), we examined how Taiwan’s democratic system developed, and how both the two main parties largely accepted a similar consensus on how Taiwan should be run domestically and did not split along the left-right lines more familiar in

As I finally slid into the warm embrace of the hot, clifftop pool, it was a serene moment of reflection. The sound of the river reflected off the cave walls, the white of our camping lights reflected off the dark, shimmering surface of the water, and I reflected on how fortunate I was to be here. After all, the beautiful walk through narrow canyons that had brought us here had been inaccessible for five years — and will be again soon. The day had started at the Huisun Forest Area (惠蓀林場), at the end of Nantou County Route 80, north and east

Specialty sandwiches loaded with the contents of an entire charcuterie board, overflowing with sauces, creams and all manner of creative add-ons, is perhaps one of the biggest global food trends of this year. From London to New York, lines form down the block for mortadella, burrata, pistachio and more stuffed between slices of fresh sourdough, rye or focaccia. To try the trend in Taipei, Munchies Mafia is for sure the spot — could this be the best sandwich in town? Carlos from Spain and Sergio from Mexico opened this spot just seven months ago. The two met working in the

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),