Sept 22 to Sept 28

Hsu Hsih (許石) never forgot the international student gathering he attended in Japan, where participants were asked to sing a folk song from their homeland. When it came to the Taiwanese students, they looked at each other, unable to recall a single tune.

Taiwan doesn’t have folk songs, they said. Their classmates were incredulous: “How can that be? How can a place have no folk songs?”

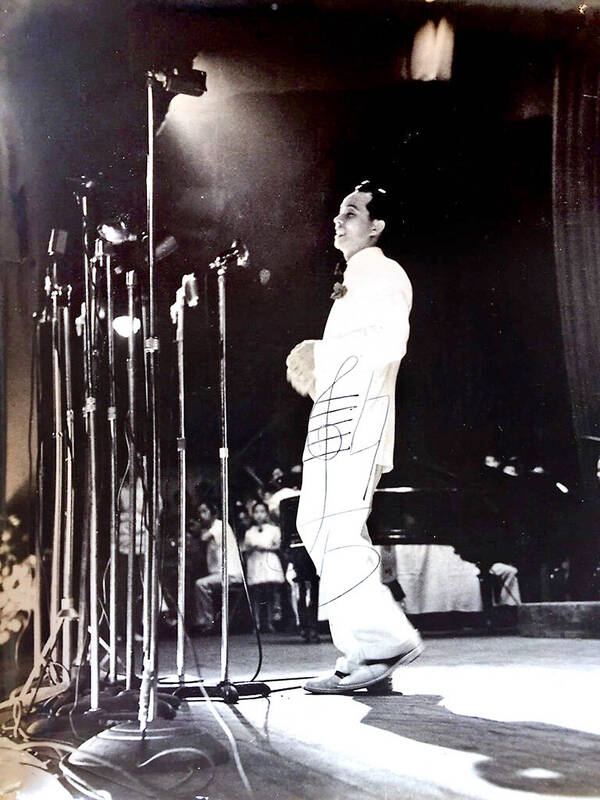

Photo courtesy of Charles Hsu

The experience deeply embarrassed Hsu, who was studying music. After returning to Taiwan in 1946, he set out to collect the island’s forgotten tunes, from Hoklo (Taiwanese) epics to operatic cart-drum songs, Hakka tea-picking ditties and Indigenous pestle dances.

It was a difficult task — he later recalled that often only people over 60 still remembered them.

“I would bring liquor and share drinks with the elders,” he told the China Daily News. “Only after they got tipsy would they hum a few fragments. We had no recorders back then, so I relied entirely on pen and paper. If I wasn’t careful, I’d miss something. And every singer had a different version, making it a headache to organize.”

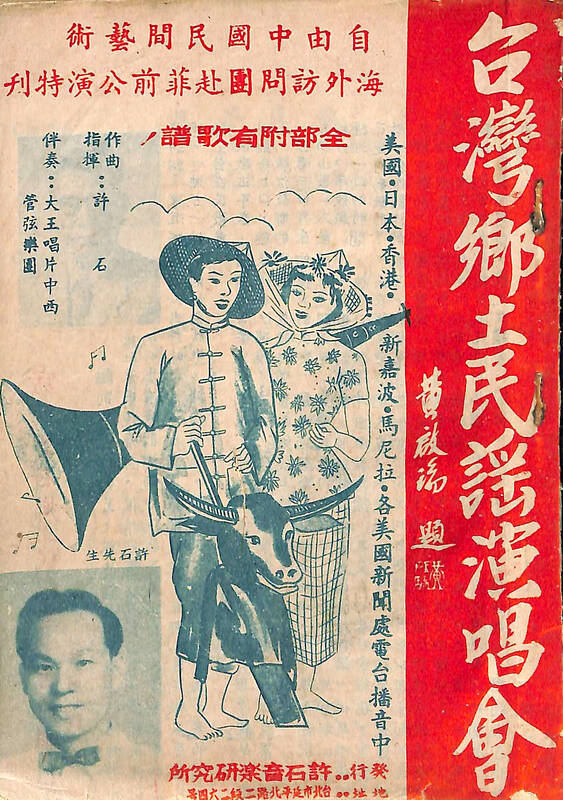

Photo courtesy of Charles Hsu

Hsu’s goal was not just to preserve tradition, but to popularize it. He carefully rearranged the melodies, inviting lyricists and intellectuals to add new words, and released the songs through his record company. Every few years, he conducted large-scale folk music presentations and toured abroad, pouring much of his savings into the effort.

MUSICAL TRAINING

Hsu was born on Sept. 23, 1919, the youngest of 11 children to a family of modest means. He enjoyed temple parades and Taiwanese opera performances as a child. As a teenager, he worked all sorts of odd jobs with his brothers, but after a car accident left him with broken front teeth, he realized that he wanted more from life.

Photo courtesy of Kuo Chih Yuan Music Association

He saved up money and headed to Japan, where he finished high school and enrolled in the Japan College of Popular Music, graduating in 1942. He later recalled that most Taiwanese who could study music abroad were from wealthy families, while he was delivering newspapers and milk every morning and also working as a truck driver.

His professors, noted composers Nosho Omura and Kyosho Yoshida, urged him not to simply imitate Japanese music but to draw inspiration from Taiwan’s life and sounds. This, in addition to the student gathering incident, instilled in Hsu a strong sense of duty to uncover and express the music of everyday Taiwanese life, writes his son Charles Hsu (許朝欽) in a biography.

Hsu spent four years as a singer for the prestigious Moulin Rouge Shinjukuza Theater and the Toho Theater, before returning home in February 1946 to care for his ailing mother.

POP SUCCESS

Once back home, Hsu wasted no time composing Southern Nocturne (南都之夜), often hailed as Taiwan’s first post-war hit song. Its lyrics originally reflected Taiwan’s hardships, but were soon rewritten into a more politically palatable love song.

With the support of lyricist and Tainan City councilor Hsu Ping-ting (許丙丁), Hsu Shih toured the country that year to great acclaim. Hsu Ping-ting would later pen countless lyrics for Hsu Shih and remained a staunch advocate for his folk music endeavors.

Hsu Shih churned out numerous classics during this period, his favorite being Anping Reminiscence (安平追想曲), which tells the love story of Ms Chin (金) and a Dutch ship doctor. While teaching music in Tainan, Hsu often visited the Anping Old Fort (Zeelandia). One day he started chatting with an old man about local history, and learned about this tale.

The song was later recorded as a musical drama, featuring Hsu’s student and Taiwanese opera diva Yang Li-hua (楊麗花), who also starred in the 1972 movie adaptation.

And Streetlight at Midnight (夜半路燈) was based on his own courtship with Cheng Shu-hua (鄭淑華), the niece of his good friend and fellow composer Yang San-lang (楊三郎). Cheng lived in Taipei, and Hsu would often wait for her under the streetlight at Tainan Railway Station, dressed in a crisp suit. They married in 1951 and had eight children.

COLLECTING TAIWAN’S MELODIES

In the summer of 1947, Hsu and future star Wen Hsia (文夏), then a high school student, traveled to Pingtung County’s Hengchun Township (恆春). He asked the guesthouse owner for someone who could sing the folk epic Melody of Memory (思想起), and soon, the legendary wandering bard Chen Ta (陳達) showed up with his moon lute. This was two decades before musicologists “rediscovered” Chen and made him a household name (see “Taiwan in Time: Searching for their ‘musical mother tongue,’” Feb. 9, 2020).

In addition to modernization, these songs also suffered from the colonial ban on folk music from 1917 to 1925, and the later kominka assimilation policies. Plus, educated Taiwanese often found them vulgar and unrefined.

Hsu continued collecting folk music until around 1960, when in September he staged the “Fourteen Years of Folk Song Gathering” concert at Taipei’s Zhongshan Hall.

“I have a dream,” he said at one of his shows. “I want those Taiwanese folk songs that have been almost forgotten to once again burn in the hearts of the people of Taiwan”

Hsu’s program was well received in Asia, but he wanted to take it a step further. In 1964, he premiered his magnum opus Symphonic Folk Songs of Taiwan (台灣鄉土交響曲), a nearly 40-minute orchestral piece blending Taiwanese instruments, hoping to carry the sounds of Taiwan to Western audiences.

LASTING LEGACY

Hsu devoted most of his earnings on his record companies and organizing shows, leaving the family in financial difficulties, yet his wife and children remained supportive.

Hsu’s final concert took place on Aug. 8, 1979 at Zhongshan Hall. He was in poor health and just had heart surgery, but he insisted on conducting the concert and was actively involved in every step. He wasn’t singing anymore due to his condition, but when the student who was meant to sing Anping Reminiscence ran late, the host asked him to sing it.

His family was worried, but Hsu finished the song, remarking, “It’s been so long, I almost forgot the words.”

He died the following year at the age of 62.

A notoriously strict teacher, Hsu trained numerous notable entertainers, including his daughters. The two eldest twins began performing as teenagers as the pop duo Taiwan Peanuts (台灣若比娜茲), and in 1970 three more sisters joined to form the Hsu Family Chinese Folk Song Band (許石中國民謠合唱團).

This was a time when the government was trying to suppress Taiwanese-language music, but they still found great success touring — especially in Japan. In 1972, the Hsu family was finally able to buy a house in Taipei. The band continued on for five years after Hsu’s death — further cementing his legacy.

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

Jan. 12 to Jan. 18 At the start of an Indigenous heritage tour of Beitou District (北投) in Taipei, I was handed a sheet of paper titled Ritual Song for the Various Peoples of Tamsui (淡水各社祭祀歌). The lyrics were in Chinese with no literal meaning, accompanied by romanized pronunciation that sounded closer to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) than any Indigenous language. The translation explained that the song offered food and drink to one’s ancestors and wished for a bountiful harvest and deer hunting season. The program moved through sites related to the Ketagalan, a collective term for the

As devices from toys to cars get smarter, gadget makers are grappling with a shortage of memory needed for them to work. Dwindling supplies and soaring costs of Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) that provides space for computers, smartphones and game consoles to run applications or multitask was a hot topic behind the scenes at the annual gadget extravaganza in Las Vegas. Once cheap and plentiful, DRAM — along with memory chips to simply store data — are in short supply because of the demand spikes from AI in everything from data centers to wearable devices. Samsung Electronics last week put out word