It was not the most eloquent line uttered in movie history, and it may have been one of the silliest: "Greetings, my friend. We are all interested in the future, for that is where you and I are going to spend the rest of our lives."

But the sentiment, as intoned by the celebrity psychic Criswell at the beginning of the 1959 astro-disaster Plan Nine From Outer Space, was a perfect way to explain the influence that the space race, then in its infancy, was already beginning to exercise on American popular culture and art - from movies and television to architecture and design.

An effect was much more than simply a spillover from the silvery streamlining of the space program. It was an increasing preoccupation with the future and technology that helped change not only the country's look in the 1950s and 1960s, but also, in some ways, its very conception of itself, as if seen anew from space.

PHOTOS: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

The architect Buckminster Fuller, one of the space age's most ardent proselytizers, put it much more coherently in his book Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth: "We are all astronauts."

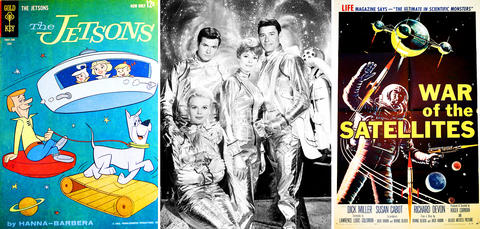

Deciding which cultural offerings from those post-Sputnik years were deep and lasting and which were probably not (space-age bachelor-pad music? The Jetsons? Barbarella? Tang?) would always be topics of impassioned debate among space aficionados. But a half-century into that once-imagined orbital future, it has become a little easier to put the era into cultural perspective.

The worlds of fashion, furniture, comic books and children's toys were all profoundly affected, often for the good.

PHOTOS: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Television and the movies, as evidenced by examples like Plan Nine, Lost in Space and Invasion of the Saucer Men, in which an alien's severed hand crawled around wreaking havoc on the big screen, did not fare quite as well.

Even so, it is difficult to imagine cinema without Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. And it is almost impossible to imagine that movie, made in 1968, looking the way it did in the absence of an American space program, even with earlier influences like the spacey designer Raymond Loewy or the architect Eero Saarinen, whose curvy 1948 Womb chair looks like something made specially for Kubrick's set.

In the realm of art, the influence was smaller and, usually, less direct. The cultural scholar Dave Hickey said he always felt that the "ice-white cube," which became the standard kind of ascetic interior in museums and galleries by the 1960s, could be traced in part right back to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

"I remember thinking at the time that, all of a sudden, we were looking at art in clean rooms like those where the astronauts suit up," Hickey, a professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, said in a recent interview.

Robert Rauschenberg was probably the most famous artist to use space imagery front and center, incorporating pictures of astronauts and space capsules into his works in the 1960s.

At Bell Laboratories, which was intimately tied up with NASA in its earliest years, Billy Kluver, an engineer, organized groundbreaking collaborations with artists, including Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol, to inject space-age technology into artworks, a program whose legacy is still felt today.

Many cultural critics say probably the biggest impact can be seen in architecture. Especially in California and elsewhere in the West, the work of architects like John Lautner transformed the look of cities and highways with upswept wing-like roofs, domes, satellite shapes and starbursts that became the dominant visual language of motels, diners and gasoline stations.

Hickey describes the look as "somewhere between Hindu temples and launching pads."

The look, sometimes called Googie, after Lautner's design for the Googie's coffee shop in Los Angeles, predated the Sputnik launching and had influences back to Wayne McAllister's curvaceous hotels and drive-ins, to Frank Lloyd Wright and even to Futurism in the 1920s. It took off along with the space race and produced buildings that tried very hard to bring the Jetsons to life, like Lautner's 1960 Chemosphere, a saucer-shaped house that looks as if it is preparing to hover out over the Hollywood Hills.

Kenneth Frampton, the architectural historian, said it was often difficult to disentangle the threads of the space-age look, whose origins come from early airplane and jet design. Frampton added that the lines of influence that began with Fuller's geodesic domes and other futuristic ideas could be traced across the ocean to Archigram, the visionary group of British architects who proposed far-out projects (never realized) like capsule-shaped living pods and suits that could expand and double as structures.

Their spirit has, in turn, inspired and animated many contemporary high-tech architects like Rem Koolhaas, Zaha Hadid and Renzo Piano, whose tubular, machinelike Pompidou Center, built with Richard Rogers, seems to evoke the space race in very specific ways.

"You could draw certain parallels between the structure of the Pompidou and the structure of the rocket-launching facilities at Cape Canaveral," said Frampton, who teaches at Columbia. "They might not have been thinking about it, but I think there is some kind of unconscious affinity there."

April 28 to May 4 During the Japanese colonial era, a city’s “first” high school typically served Japanese students, while Taiwanese attended the “second” high school. Only in Taichung was this reversed. That’s because when Taichung First High School opened its doors on May 1, 1915 to serve Taiwanese students who were previously barred from secondary education, it was the only high school in town. Former principal Hideo Azukisawa threatened to quit when the government in 1922 attempted to transfer the “first” designation to a new local high school for Japanese students, leading to this unusual situation. Prior to the Taichung First

The Ministry of Education last month proposed a nationwide ban on mobile devices in schools, aiming to curb concerns over student phone addiction. Under the revised regulation, which will take effect in August, teachers and schools will be required to collect mobile devices — including phones, laptops and wearables devices — for safekeeping during school hours, unless they are being used for educational purposes. For Chang Fong-ching (張鳳琴), the ban will have a positive impact. “It’s a good move,” says the professor in the department of

On April 17, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) launched a bold campaign to revive and revitalize the KMT base by calling for an impromptu rally at the Taipei prosecutor’s offices to protest recent arrests of KMT recall campaigners over allegations of forgery and fraud involving signatures of dead voters. The protest had no time to apply for permits and was illegal, but that played into the sense of opposition grievance at alleged weaponization of the judiciary by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to “annihilate” the opposition parties. Blamed for faltering recall campaigns and faced with a KMT chair

Article 2 of the Additional Articles of the Constitution of the Republic of China (中華民國憲法增修條文) stipulates that upon a vote of no confidence in the premier, the president can dissolve the legislature within 10 days. If the legislature is dissolved, a new legislative election must be held within 60 days, and the legislators’ terms will then be reckoned from that election. Two weeks ago Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) proposed that the legislature hold a vote of no confidence in the premier and dare the president to dissolve the legislature. The legislature is currently controlled