Every so often, a purely local dispute rises above its station and assumes national importance. This was the case with the Cape Wind project, a proposed wind farm that seemed to have everything going for it: It would deliver badly needed additional electric power to energy-hungry New England, reduce utility bills for everyone and cut down on air pollution. There was just one little problem. The spinning windmills would be located in Nantucket Sound, within view of some very expensive homes and some very wealthy and powerful citizens.

Cape Wind is a cautionary tale. Wendy Williams, a journalist who lives on Cape Cod, and Robert Whitcomb, a vice-president and editorial page editor of the Providence Journal, give a blow-by-blow account of the project from its inception in 2001 to its ambiguous conclusion today. In so doing they show how quickly self-interest can be rallied to frustrate the broader public interest and how difficult it may be to change old habits of energy consumption in the US.

This is a story that seems to have everything: waterfront mansions, yachts, a tenacious blue-collar entrepreneur, bare-knuckled political infighting at the state level and high-stakes political poker in Congress. It offers the delicious spectacle of self-described environmentalists, infatuated with the idea of alternative energy, tying themselves into knots trying to explain why a wind farm would be a splendid idea anywhere but in Nantucket Sound. Throw in a few Kennedys, and you have the ingredients for a first-rate politico-eco drama.

Alas the authors squander this opportunity. As unabashed cheerleaders for Cape Wind and seething with indignation at its opponents, they make no pretense of laying out the facts evenhandedly. They have a white-hat hero, Jim Gordon, the Boston energy entrepreneur who conceived of Cape Wind and fights the political power brokers — local, state and national — every step along the way. They have deep-dyed villains who appear onstage to the sound of authorial hisses: notably Senator Edward Kennedy, whose family compound in Hyannis looks out on the sound, and Mitt Romney, then governor of Massachusetts, who began nearly every speech on Cape Wind with "I support renewable energy" and then blocked the project at every turn. Their partner in crime is John Warner, the senior senator from Virginia, who has had longstanding ties to Cape Cod through his first wife, Catherine Mellon.

The premise of the book is simple. As the authors tell it, a cabal of martini-swilling fat cats, surreptitiously encouraged by Senator Kennedy, worked the political system night and day to stop a beneficial utility project so that they could enjoy an unencumbered view from their energy-wasting mansions and sail their yachts without worrying about running into a wind turbine. They wrote big checks, told big lies and intimidated anyone foolish enough to get in their way, aided and abetted by a servile local newspaper, the Cape Cod Times, and the Alliance to Protect Nantucket Sound, depicted as a thoroughly unscrupulous advocacy group financed by local residents.

The facts are damning enough. The wind farm, consisting of 130 propellered turbines installed over an area of about 67km2, would generate up to 500 megawatts of clean energy. It would also reduce Cape Cod's dependence on two fossil-fuel plants that help make its air among the most polluted in New England. Nevertheless local grandees and celebrities, among them the former CBS anchorman Walter Cronkite and the historian David McCullough, came out foursquare against the project even before details were known. Opposition boiled down to four words: not in my backyard.

Williams and Whitcomb do a good job of showing how the rich make local government work for them, pulling strings discreetly from behind the curtain. But they pile on, with sneering quotation marks, insulting epithets and heavy-handed sarcasm.

At times, the authors barely bother to present a case. When Larry Wheatley, a Republican candidate for state office put up by opponents of Cape Wind, is introduced, they write that "he said he was an attorney, and he seemed to be selling real estate in Osterville." Well, was he or wasn't he?

An economist named David Tuerck, of the Beacon Hill Institute, issued a report claiming that Cape Wind would cause economic losses to Cape Cod by lowering property values and driving away tourists. The authors simply dismiss the analysis as being "of doubtful quality" and repeat a characterization of Tuerck as "a right-wing economist for hire." The report might well have been shoddy — the Beacon Hill Institute received US$100,000 from a foundation opposed to Cape Wind — but there is no way of knowing, since the authors do not deign to pick it apart.

The man in the white hat manages to pull a few rabbits out of it. Gradually, as the furor over Cape Wind gained national attention (in part because of an article in the New York Times Magazine), environmental groups like Greenpeace and powerful politicians in favor of alternative energy projects began to apply effective counterpressure. Cronkite, after sitting down and talking over the project with Gordon, withdrew his opposition. One by one, legislative barriers thrown up at the last minute, behind closed doors, were overcome by some judicious arm twisting. At the moment, if permits are granted, Cape Wind can move forward.

As the authors make clear, Gordon and the supporters of wind power might win the battle but lose the war. Companies interested in developing projects like Cape Wind now know that developing offshore wind farms might not be worth the blood, sweat and tears. Everyone, like Romney, loves alternative energy. For everyone else.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

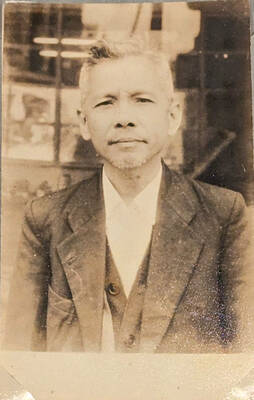

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name