Simon Rattle is already on his second cup of Starbucks' finest before he starts his rehearsal at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, for a production of Debussy's only opera, Pelleas et Melisande. After a run-through of the first scene of act three, he's not completely happy. "It's a bit early in the morning: we need to find our velvety sound; it still sounds too heavy." He wants more from the orchestra's cello section; one chord, maybe the most violent moment in the whole piece, needs to be played like a "small nuclear explosion."

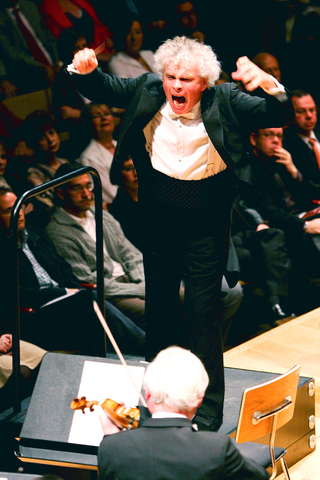

What's miraculous is that in the space of an hour or so, Rattle transforms the sound of the Royal Opera orchestra. Instead of the lumpen playing at the start, there is shimmering, atmospheric brilliance. The singers grow in confidence as imperfections of ensemble are ironed out, and the performance blooms. It's an object lesson in how to rehearse, a revelation of Rattle's gifts as a communicator, verbally and gesturally coaxing the best out of his musicians.

Rattle's rise from UK-born wunderkind, to savior of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, and, in 2002, to his assumption of the most challenging job in music at the age of just 47, is the stuff of legend. His has been a near faultless progress from teenage prodigy to elder statesman. During his time in Birmingham, from 1980 to 1998, Rattle could do no wrong. As a public advocate for serious music and music education, Rattle was classical music's most powerful and vocal ambassador. When he left the CBSO in 1998, he had the musical world at his feet, but the Berlin job was always going to be the most tempting. Ever since his debut with the Berliners in 1987 with Mahler's Sixth Symphony, they were the players that inspired him most. And, in June 1999, the orchestra voted for Rattle over Daniel Barenboim to replace Claudio Abbado as their maestro.

PHOTOS: EPA

But it hasn't all been plain sailing. For the first time in his career, Rattle has faced a critical onslaught, from sections of the German media. At the same time, the British press have used his success abroad as a chance to put the boot in. "The Tony Blair of classical music" is a common epithet, to suggest spin and a tarnished reputation. But it's not a completely erroneous analogy. Like Blair, Rattle has tried to be all things to all people in Berlin, playing a huge variety of repertoire in his first five seasons, from Mahler to Mark-Anthony Turnage, Bernstein to Boulez, and inviting conductors such as French Baroque expert William Christie — whose early music style is a long way outside the Berliners' musical comfort zone — to train his players in a new musical versatility. After all, this is the orchestra that is the guardian of the central European tradition, the mighty Austro-German hegemony of Beethoven, Brahms, Bruckner and Mahler, not Rameau or Ravel. What Rattle is attempting is a musical form of multiculturalism, in which the orchestra's brilliance lies not so much in their competence in one repertoire, but how the musicians can adapt to different styles of music.

The fact that Debussy is so far from the heart of the Berlin Philharmonic's musical identity is at the root of the criticism of Rattle's time in Berlin: in moving away from the center of what the orchestra does, he's in danger of losing its musical essence. Rattle sees it differently. "Of course there's a huge debate about what is our Spielkultur [playing culture], and whether we should be playing new pieces that aren't in our Spielkultur. I mean, the answer is, of course you should be, and the question is, what can the Spielkultur bring to this new repertoire?" He compares the various styles of music he asks them to play to "putting on different clothes: I don't ask them to change their body. And of course, just as there's a danger in too much specialization, there's a danger in simply flying all over the globe."

But it's the body that's the problem. When Rattle first went to conduct in Berlin 20 years ago, he joked that it was the only orchestra he couldn't ask to produce a real Berlin Phil sound — "at least it broke the ice," he says. That sound was the indelible, Karajan-inspired voluptuousness that defined the reputation of the Berlin Phil around the world. "It's a real 'wuah' sound that starts underneath," he says, "a deep, bass-up sound, which is recognizably theirs. It's like an enormous heat source that comes at you, and you feel as though you can burn in it." It's also the most viscerally exciting sound in orchestral music: at the orchestra's recent Barbican concert in London, there were moments in Dvorak's Seventh Symphony when the sheer power of the playing, above all the string section and their titanic double-basses, seemed almost unbearably intense, like an untamed force of nature. It's a completely thrilling phenomenon; Rattle's problem is how to harness it.

Next season brings the biggest challenge of them all, the litmus test for any conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic: Rattle will conduct a Beethoven symphony cycle, his first with the orchestra (in 2002, he recorded a cycle of the nine symphonies with the Berliners' main rival for the "greatest orchestra in the world" tag, the Vienna Philharmonic). It seems like a return to what the orchestra knows best. Not so, says Rattle. "Part of the thing I've learned over the past few years is that this is an orchestra which doesn't have an enormous shared memory. There has been such a huge turnover of players in recent years, and many have never played a Beethoven cycle. It's now a very young orchestra, with many people in their 20s, and 20 different nationalities. Guy Braunstein, one of our sensational leaders, comes from a string quartet background. Angela Merkel asked us to play Beethoven Five for the Treaty of Rome concert earlier this year, and Guy was playing his first ever Beethoven Fifth. You would just not imagine! When we played that Dvorak Seven, nearly half of them had never played it. What was sweet was that a lot people said to me, 'You know, this is really a wonderful piece,' as though that was an incredible surprise, and even — the highest compliment — 'I like this symphony, it's almost like Brahms.'"

All this means Rattle has the chance to create a tradition in Berlin, not simply continue one. He's at pains to talk about how collaborative the players are in all this — "It's the kind of orchestra where, if you have 128 players, you're talking a minimum 150 opinions" — but ultimately, "it's my hands, or my baton, and that has to be its own authority." Off the podium, Rattle has also stamped his vision on the future of the Berlin Phil. He has won key political battles with the city, fighting for the orchestra's finances and salaries, and he set up the orchestra's first education department as soon as he arrived.

Rattle will always have something to prove in Berlin, to the orchestra, to his audiences, to his critics. But if anyone has the energy, drive, and force of will to deal with all this, it's him. What he is attempting is to have it both ways: to open Berlin up as an orchestra in terms of its repertoire and its relationship with the city, and develop the ensemble as the definitive orchestra in the core German tradition. It's not something you can do in five years, or even 10: it's a project that could last Rattle the rest of his musical life.

And he's prepared for the backlash that comes with the position. "Look, I would dearly love it if everyone enjoyed everything I did, but even I'm not that naive and optimistic. Anyone who conducts this orchestra is going to be the antichrist to somebody. Maybe I'm just more successful at being the antichrist than some others."

April 28 to May 4 During the Japanese colonial era, a city’s “first” high school typically served Japanese students, while Taiwanese attended the “second” high school. Only in Taichung was this reversed. That’s because when Taichung First High School opened its doors on May 1, 1915 to serve Taiwanese students who were previously barred from secondary education, it was the only high school in town. Former principal Hideo Azukisawa threatened to quit when the government in 1922 attempted to transfer the “first” designation to a new local high school for Japanese students, leading to this unusual situation. Prior to the Taichung First

The Ministry of Education last month proposed a nationwide ban on mobile devices in schools, aiming to curb concerns over student phone addiction. Under the revised regulation, which will take effect in August, teachers and schools will be required to collect mobile devices — including phones, laptops and wearables devices — for safekeeping during school hours, unless they are being used for educational purposes. For Chang Fong-ching (張鳳琴), the ban will have a positive impact. “It’s a good move,” says the professor in the department of

On April 17, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) launched a bold campaign to revive and revitalize the KMT base by calling for an impromptu rally at the Taipei prosecutor’s offices to protest recent arrests of KMT recall campaigners over allegations of forgery and fraud involving signatures of dead voters. The protest had no time to apply for permits and was illegal, but that played into the sense of opposition grievance at alleged weaponization of the judiciary by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to “annihilate” the opposition parties. Blamed for faltering recall campaigns and faced with a KMT chair

Article 2 of the Additional Articles of the Constitution of the Republic of China (中華民國憲法增修條文) stipulates that upon a vote of no confidence in the premier, the president can dissolve the legislature within 10 days. If the legislature is dissolved, a new legislative election must be held within 60 days, and the legislators’ terms will then be reckoned from that election. Two weeks ago Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) proposed that the legislature hold a vote of no confidence in the premier and dare the president to dissolve the legislature. The legislature is currently controlled