Louis Comfort Tiffany and Laurelton Hall: An Artist's Country Estate is the rare exhibition that comes with its own porch. And not just any porch. The Daffodil Terrace temporarily installed at the Metropolitan Museum is larger than many Manhattan apartments. Its tall marble columns are topped with clusters of yellow flowers — daffodils — made of blown glass, the material in which Tiffany achieved his greatest eloquence.

Reassembled here for the first time since Laurelton Hall burned to the ground in 1957, the Daffodil Terrace adds a fitting Temple of Dendur splendor to a strange and lovely exhibition. It has been organized by Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, the Met's curator of American decorative arts, and presents a series of beautiful objects in search of a ghost.

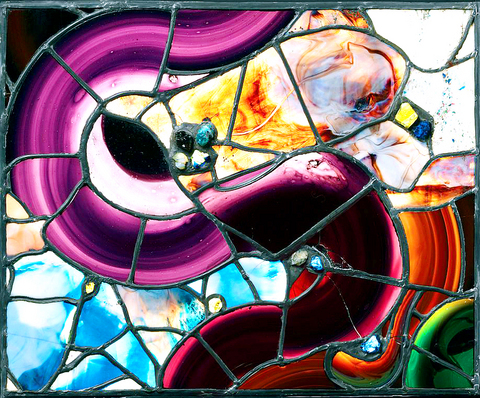

The Daffodil Terrace once connected the dining room and the gardens at Laurelton Hall, the grand estate that Tiffany built for himself from 1902 to 1905 on 580 extensively landscaped acres overlooking Long Island Sound. It is displayed here in an enormous gallery, along with the stained-glass windows whose trailing wisteria vines brought the garden into the dining room, and the imposing white marble mantel whose three glass mosaic clocks let diners keep track of the time, the day and the month.

PHOTS: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Tiffany was born in 1848, the industrious son of a wealthy founder of the luxury-goods business soon known as Tiffany & Co. He set out to be a painter, touring Europe and the Mediterranean and becoming especially smitten with Orientalism. But he had more facility than originality, as the paintings and watercolors here attest.

An inveterate shopper and cultural scavenger, he must have realized that his love of the exotic — Egyptian, Persian, Asian and North African — might be best expressed in objects, and that these objects could be orchestrated into seductive living environments that no painting could match.

By 1875 Tiffany was spending time in Brooklyn glasshouses, learning the craft. By 1885 he was in the process of melding the English Arts & Crafts notion of the unified interior and the Aesthetic Movement's love of eclecticism into an encompassing vision of his own that presaged Art Nouveau.

He oversaw a succession of companies and factories where as many as 300 artisans produced leaded-glass windows and lamps; favrile-glass vases made by a technique of his own invention; all kinds of objects in enamel and carved wood; and textiles, furniture and rugs. With these resources Tiffany designed lavish multicultural living quarters for the richest, most adventuresome figures of the Gilded Age, including the collectors H.O. and Louisine Havemeyer.

Had Laurelton Hall survived, it would have been Tiffany's ultimate work of art, a monument to a total vision on the scale of Frederic Edwin Church's Persian-Victorian fantasy, Olana, built in the late 1860s high above the Hudson River near Hudson, New York.

In 1918 Tiffany established a foundation to maintain the estate in perpetuity as a house museum and an artist's colony. But the Tiffany Foundation fell on hard times. Although it exists today as a grant-giving body, in 1946 it auctioned off the contents of the house, divided the property into parcels and sold those too. The new owners of the main house rarely visited.

Within days of the fire and at the Tiffany family's request, Hugh F. McKean, an artist who had received a residency at Laurelton Hall in 1930, went to the smoldering ruins and pulled out anything that was relatively intact. Later he and his wife, Jeannette Genius McKean, purchased the remains of Laurelton Hall from salvagers.

These objects, including the Daffodil Terrace, became the core holdings of the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art in Winter Park, Florida, which the McKeans had established in 1942 and named for Jeanette McKean's grandfather. In 1978 the McKeans gave the Met another Tiffany porch, Laurelton Hall's entrance loggia, which is on permanent view in the Engelhard Court in the museum's American Wing.

The exhibition gives an overwhelming account of Tiffany's talents and interests. His breakfast furniture indicates that in the early 1880s he had thoughts about simple structures and white surfaces that occurred to Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Koloman Moser decades later. There are touches of endearing modesty, like a Steinway upright piano designed by Tiffany and based on a Middle Eastern chest that seems to be inlaid with mother-of-pearl but is actually just ingeniously carved and painted.

There are also examples of Japanese, Chinese and American Indian objects that Tiffany owned, was inspired by and displayed at Laurelton Hall, including two astounding Qing dynasty headdresses made of gilded silver inlaid with brilliant blue kingfish feathers.

But the main attraction is the glass, along with the small, murky photographs of Laurelton Hall's interiors and of Tiffany's city interiors that led up to them. The show encompasses a near-retrospective of stained-glass windows, and the best reveal the different ways Tiffany translated both the gestural and the descriptive powers of painting into an altogether more tactile medium.

While Tiffany is available to us mostly in bits and pieces, objects like these seem to carry whole worlds within them.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)

Today Taiwanese accept as legitimate government control of many aspects of land use. That legitimacy hides in plain sight the way the system of authoritarian land grabs that favored big firms in the developmentalist era has given way to a government land grab system that favors big developers in the modern democratic era. Articles 142 and 143 of the Republic of China (ROC) Constitution form the basis of that control. They incorporate the thinking of Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙) in considering the problems of land in China. Article 143 states: “All land within the territory of the Republic of China shall