In a plaza near the brand-new Louis Vuitton store on Zhongshan North Road, couples gather to take pictures of themselves and a super-sized piece of LV luggage. There are even two security guards to stop them clambering over the giant trunk, with it's distinctive LV monogram pattern and brass locks.

Opposite stands a white Italian marble monument to taste, the latest LV flagship store. The stones have been laser monogrammed with square holes and are backlit by an ethereal orange glow at night. A smartly suited gentleman opens the door and you are swept into another world.

Designed by the office of Japanese architect Inui Kumiko, the overall impression is of opaque surfaces bearing the fashion company's signature "damier" pattern; teak and stainless steel. The carpets are deep and lush. There are large mirrors that show looped videos of LV collections.

PHOTOS COURTESY OF LOUIS VUITOON

A mixture of the well-heeled and the curious peruse the store, as if they were in an art gallery. They stop, they ooh and they aah. There are four floors and a red embroidered leather elevator to take you up and down. But most people take the tour up the stairs, all the way to the bookshop at the top.

It's only the second LV bookstore in the world, with glossy tomes like African Wisdom 365 Days by Danielle and Olivier Follmi, which features the apposite advice from Birago Diop, "Listen more often/To things than to beings."

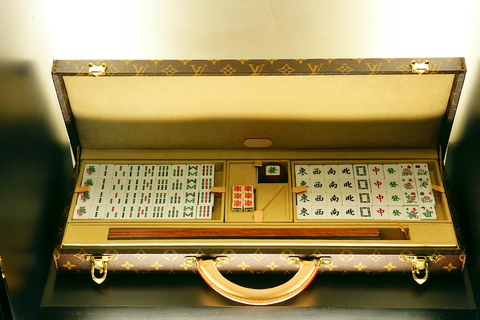

And some of the items on display do have a lot to say for themselves. Seventy percent of LV sales are bags and these range in price from NT$20,000 to NT$40,000. Diamond encrusted gold pendants are big sellers; and the 12 Skyline 101 watches going for NT$2 million have all been snapped up. There's also menswear, glasses, women's fashion and accessories.

There are no price tags for the items in the store. As the saying goes, "If you have to ask, then you probably can't afford it." Many of LV's customers are asking for made-to-order or special order goods which cost even more, says LV communications manager Ben Huang (

The luxury goods market is paradoxical. Buying into a lifestyle means paying a premium so that other people know you've got money. The nouveau riche are most likely to announce their rise by appropriating symbols of wealth.

Yet, money seems to be a dirty word. Curiously for a company that reportedly opened 23 stores and increased net profits by 50 percent last year, discussion of money seems to be taboo.

"We don't talk about money because that's not what a luxury goods manufacturer does," says Huang, who brushes aside questions about how much the store cost.

He then squashes reports that last week's fabulous opening ceremony featuring the South Korean star Rain and the after party at Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall cost US$1.5 million. He does admit, however, the cast of A-list celebrities and their acolytes quaffed 2,700 bottles of champagne.

You can tell that Huang is a practiced hand at fending off questions about fake LV items as he is adept at reiterating the company line that it cooperates with the police and government to reduce piracy.

"It's not the company's responsibility to tell people whether or not an item is fake. A lot of people ask, `How you can tell?' We say, come to the store, then it can be guaranteed."

As for the argument that fake goods fuel a "need" for the real thing, he says that since counterfeiters operate illegally, the market does not officially exist so he cannot comment on it. "I can only talk about LV in Taiwan."

"We did not build this maison just for profit. This is more about art and lifestyle and providing something special here," Huang said. "It's about inspiration and the lessons learned from 150 years of experience [since the founding of Louis Vuitton]. Our products are in museums. ... Maybe we are not the first in the market with some goods, but we do want to be the best."

Looking around the store he has a point.

Louis Vuitton Maison is at 47, Zhongshan N Rd Sec 2, Taipei (台北市中山北路二段47號).

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.