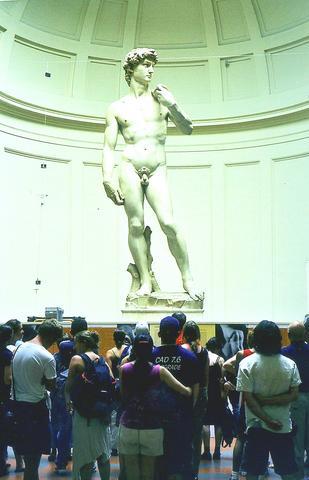

As a measure of this city's nervousness about restoration of its Renaissance masterpieces, Michelangelo's David was unveiled on Monday, after eight months of cleaning, to proud claims that this 4.25m-high marble statue looked little different. "An invisible cleaning," Antonio Paolucci, the superintendent of Florentine art, said reassuringly, "like washing the face of a child."

For anyone familiar with David, though, this monumental sculpture did look different, definitely cleaner and generally more presentable in preparation for celebrations marking the 500th anniversary of its placement in the Piazza della Signoria in September 1504. Paolucci's caution, however, evidently reflected a desire not to reawaken the controversy that preceded this US$500,000 restoration.

One year ago Agnese Parronchi, the restorer hired to clean the statue where it now stands in the Galleria dell'Accademia, resigned to protest the so-called wet cleaning method imposed on her by Florentine experts. Her warning of damage to the work were soon echoed by James Beck, a Columbia University art historian and president of ArtWatch International, who organized a petition signed by 55 international art historians calling for further study before cleaning.

PHOTO: NY TIMES

In July, however, Paolucci gave the go-ahead for the restoration. And in September a new restorer, Cinzia Parnigoni, began using the approved wet method by applying distilled water through compresses of cellulose pulp on top of Japanese paper. In some sections where wax dating back two centuries had accumulated, Parnigoni also used white spirits to remove the wax.

not too white

"I would call the result `less gray,"' Parnigoni said. "But I hope it is not too white."

Beck, who visited the Accademia last month to observe the cleaning, said he still felt the restoration unnecessary. "But this is not a drastic cleaning," he said in a telephone interview from New York, "which was a victory for our side because if we had not spoken out, they would have cleaned it much more." He said that nonetheless, by using white spirits, the museum had broken its pledge not to employ solvents.

Franca Falleti, director of the Accademia, said the white spirits were used only to dissolve wax and at no point touched the marble. Unlike Paolucci, however, who spoke repeatedly of "invisible cleaning," Falleti was eager to show, with before and after photographs, that many stains and blotches had been removed. Some, though, were too ingrained to be washed away with distilled water and have been left.

The marks on David recount much of the statue's life story, starting with the 5.2m-tall marble bloc from Carrara that had been exposed to the elements for 40 years before Michelangelo began transforming it. "It is very poor quality marble," Parnigoni said after working inches from its surface for months on end. Even Michelangelo had to spend four months polishing the marble before it was presented to the public in 1504.

In 1527, while standing in the Piazza della Signoria, the sculpture lost the lower half of its left arm during a riot. The arm was then reattached with a metal bar and covered with a white mixture of lime and sand. Since this strip has aged and colored in a different way from the rest of the marble, Parnigoni removed the original sealing matter and replaced it with fresh plaster. To her credit, the connecting point is barely visible.

The restoration history of David has also left its marks. In 1810 the statue was covered in wax for protection; in 1843 this wax along with Michelangelo's original patina was disastrously removed with hydrochloric acid. A wiser form of conservation took place in 1873, when the statue was brought indoors to the Accademia. But in 1991 an unbalanced Italian artist smashed a toe on its left foot with a hammer, and this too had to be restored.

Paolluci and his team say that what Accademia documents describe as restoration involves only conservation, although the work done here seems to lie somewhere between the two. In some areas the once dull marble has recovered its shine, with the front of the figure's torso again catching light and shadow. Some vertical stains, perhaps remnants of streams of rainwater, have also been removed.

`David' lives

Scientists also have carried out detailed studies of the environment in which David now lives. They concluded, for instance, that both the temperature and gaseous pollutants monitored around the statue were at acceptable levels. But they also noted that larger dust particles introduced by some 2 million visitors per year quickly soiled the marble "and threaten to cancel out the results obtained with the newly completed cleaning."

Parnigoni said that to prevent a dust buildup she planned to clean the statue with a hand-held vacuum cleaner every six weeks. Temperatures around David will continue to be monitored, and ultraviolet and other photographic techniques will be used to identify the accumulation of gypsum and other harmful substances on the marble surface. Perhaps most alarming, however, is the fresh recognition by Florentine experts that David would not be safe in case of a major earthquake. In documents provided to the press today, the experts are quoted as saying, "Given the importance of the work, we consider it necessary to take even this extreme hypothesis into consideration." Since Florence lies in an earthquake zone, the hypothesis is not extreme.

The principal message accompanying the unveiling, however, was that all was well with David. "I wonder if people can see the difference?" asked Willem Dreesmann, president of a Dutch foundation, Ars Longa Stichting, which financed the studies and restoration along with the American-based Friends of Florence.

"All kinds of stains have been removed," he said, "but you can only see this at close quarters."

Paolucci was more eager to minimize what has been done here. "A restoration that doesn't look like a restoration is always the best kind," he said. "David is the same as ever. For journalists this is a letdown because there is no controversy."

Beck, though, was not about to give up. "They just sort of tidied it up," he said, "and created a spectacle to get more visitors and sell more products."

The Nuremberg trials have inspired filmmakers before, from Stanley Kramer’s 1961 drama to the 2000 television miniseries with Alec Baldwin and Brian Cox. But for the latest take, Nuremberg, writer-director James Vanderbilt focuses on a lesser-known figure: The US Army psychiatrist Douglas Kelley, who after the war was assigned to supervise and evaluate captured Nazi leaders to ensure they were fit for trial (and also keep them alive). But his is a name that had been largely forgotten: He wasn’t even a character in the miniseries. Kelley, portrayed in the film by Rami Malek, was an ambitious sort who saw in

Last week gave us the droll little comedy of People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) consul general in Osaka posting a threat on X in response to Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi saying to the Diet that a Chinese attack on Taiwan may be an “existential threat” to Japan. That would allow Japanese Self Defence Forces to respond militarily. The PRC representative then said that if a “filthy neck sticks itself in uninvited, we will cut it off without a moment’s hesitation. Are you prepared for that?” This was widely, and probably deliberately, construed as a threat to behead Takaichi, though it

Among the Nazis who were prosecuted during the Nuremberg trials in 1945 and 1946 was Hitler’s second-in-command, Hermann Goring. Less widely known, though, is the involvement of the US psychiatrist Douglas Kelley, who spent more than 80 hours interviewing and assessing Goring and 21 other Nazi officials prior to the trials. As described in Jack El-Hai’s 2013 book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist, Kelley was charmed by Goring but also haunted by his own conclusion that the Nazis’ atrocities were not specific to that time and place or to those people: they could in fact happen anywhere. He was ultimately

Nov. 17 to Nov. 23 When Kanori Ino surveyed Taipei’s Indigenous settlements in 1896, he found a culture that was fading. Although there was still a “clear line of distinction” between the Ketagalan people and the neighboring Han settlers that had been arriving over the previous 200 years, the former had largely adopted the customs and language of the latter. “Fortunately, some elders still remember their past customs and language. But if we do not hurry and record them now, future researchers will have nothing left but to weep amid the ruins of Indigenous settlements,” he wrote in the Journal of