In The Station Agent a man named Fin settles into a remote outpost -- a rundown train depot in the wilds of New Jersey -- that is so restful it seems perfect for him. The movie's writer and director, Tom McCarthy, has such an appreciation for quiet that it occupies the same space as a character in this film, a delicate, thoughtful and often hilarious take on loneliness.

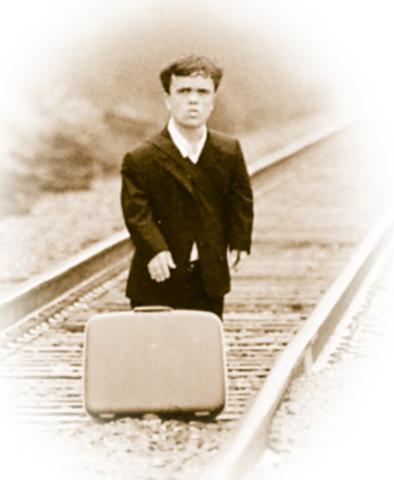

The Station Agent played at the Sundance Film Festival last year, and it's a relief to see it finally released; it's the kind of appetizing movie you want to share with others. Fin (Peter Dinklage), with his low, rational voice and intense stare, has moved into the remote spot after inheriting the depot, a dingy yet lovely shack out of a Walker Evans photograph, from Henry (Paul Benjamin), his mentor and the owner of the model-train store where Fin works in mournful silence.

Fin is 1.32m -- he has no problem referring to himself as a dwarf -- but Henry, with his sour expression and slack shoulders, seems even smaller, though he's of average height. The unperturbed air seems to take something out of him: he could be waiting to die.

McCarthy treats Fin's new life as if his protagonist were emerging from underwater and had to adjust to the onrush of aural assault. Much of this comes from Joe (Bobby Cannavale), the relentlessly friendly and talky Cuban who pulls up every day in his food truck to run what must be the loneliest retail location not staffed by the Maytag repairman. Hawking coffee and fanning up a cloud of busy, pushy and likable chatter, Joe elbows his way into the taciturn Fin's life.

Fin's obsession is trains, which he doesn't really want to talk about. He'd rather work with them, and with the depot he's been left what is essentially the world's largest model-train set. The station, though, is mostly deserted, and it provides an incomplete fantasy. For Fin the dream always seems half-empty at best.

The director plays up the amusing contrasts between the serene, diminutive Fin, whose dignity seems unassailable until he's finally ruffled, and the big, buffed Joe, whose unremitting volubility is cotton-candy charm. He's a puppy who can't help trailing after someone he adores and he uses words to mark his territory; the pair's relationship is goofily enchanting.

Joe is aggressive simply because he takes up so much space, and The Station Agent, which opens today in New York and Los Angeles, allows Cannavale to give his finest performance. There are depths of neediness and happiness coexisting in him and he doesn't bother to separate the warring factions in this charismatic supporting turn.

Dinklage's generosity should also be noted; he can be a forceful actor. He proved his worth in Tom DiCillo's making-of-an-indie-film-disaster comedy, Living in Oblivion. In that film he portrayed a cliched dwarf in an imagined dream sequence and verbally burned a layer of skin and nerve endings off the movie-within-a-movie's director (Steve Buscemi), flaying him for his lack of

imagination.

A movie about a dwarf certainly flirts with being cringe-worthy, at least in the abstract, but McCarthy deals with his creations as characters. What's most important about Fin is the detachment he imposes on himself, his resignation to loneliness. But his vulnerability becomes evident during a drunken rage in a tavern, when he shows why he keeps himself emotionally locked away. After being subjected to insults, he biliously shouts to gawkers in the bar, "Take a good look."

Joe's alone, too, and clings to the silent, brooding Fin as if he were a refrigerator magnet. When the grieving artist Olivia (Patricia Clarkson) literally barrels into the picture -- she nearly runs over Fin with her car -- The Station Agent takes on a deeper, more tantalizing shape. Clarkson has been delivering meaty, juicy plums to movies for several years; she's become the Barry Bonds of low-budget film.

Olivia is flushed with pain, and embarrassed by it. The power in Clarkson's performance comes from Olivia's recognizing parts of herself that she's been suppressing.

These three loners slowly melt into one another, but the relationship doesn't come easily to any of them. Their unspoken anguish says plenty, as does Fin's ability to provoke conversation from those who insert themselves into his circle. He clearly doesn't seek them out, except one. He does show some tenderness to a young visitor to his depot, a little girl, Cleo, played with unapologetic curiosity by Raven Goodwin. She's the one person Fin will deal with directly, and his patience tickles her; it compels her to spray him with questions.

This exception aside, McCarthy proves himself so crafty at making the unvoiced sentiments the heart of the film that the movie becomes shocking in moments when Fin vents his fury. If he weren't allowed the opportunity, however, you'd worry that The Station Agent might implode, folding in on itself in pent-up emotion.

McCarthy does allow the movie bigger scenes, providing a burst of contentment for the withdrawn Fin. In one, Joe drives next to a train, while Fin, a quiet smile on his face, catches the locomotive with his video camera. After that, it's a return to the depot, which is such a welcoming, ramshackle oasis that you think the producers might offer it on eBay one day. I'd buy it.

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful

Jan. 12 to Jan. 18 At the start of an Indigenous heritage tour of Beitou District (北投) in Taipei, I was handed a sheet of paper titled Ritual Song for the Various Peoples of Tamsui (淡水各社祭祀歌). The lyrics were in Chinese with no literal meaning, accompanied by romanized pronunciation that sounded closer to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) than any Indigenous language. The translation explained that the song offered food and drink to one’s ancestors and wished for a bountiful harvest and deer hunting season. The program moved through sites related to the Ketagalan, a collective term for the