On Friday, the Museum of World Religions (世界宗教博物館) opens in Yungho, Taipei County. The NT$2 billion museum represents the culmination of efforts by both professional museum workers and religious figures over the last decade.

With religious leaders from around the world set to attend the opening, a Global Commission for the Preservation of Sacred Sites is being launched at the same time. Arising out of the religious and secular worlds' failure to prevent the destruction of the Bamiyan statues in Afghanistan earlier this year, the commission hopes to work closely with UNESCO and the World Monument Fund, and gain the support of religious organizations around the world.

Both the museum and commission are the work of a Taiwanese Buddhist group based on Lingjiou Mountain near Fulung, Taipei County. A relatively new but fast-growing group on Taiwan's religious scene, the Wusheng Monastery (無生道場) is home to more than 100 monks and nuns.

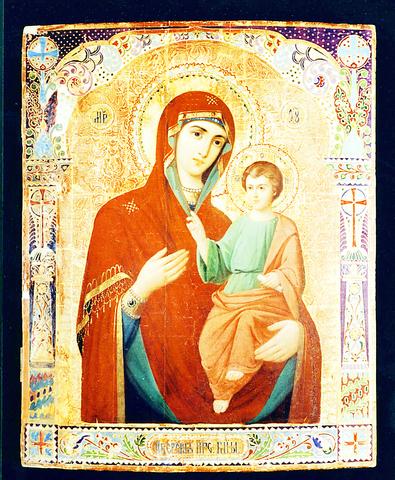

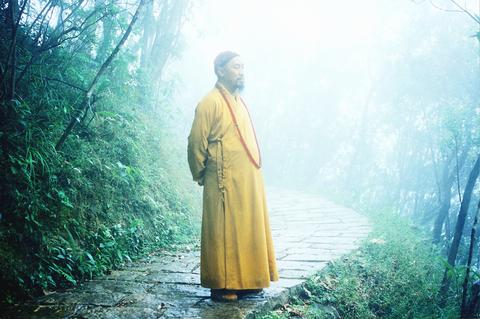

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE MUSEUM OF WORLD RELIGIONS

Unlike some other Buddhist organizations that devote their time to studying sutras and reciting prayers for the dead, or adding temples to the nation's skyline, the Lingjiou monastics are better known for practicing a modern form of "engaged Buddhism."

Their modern lifestyle of world travel, new cars and expense accounts has raised some eyebrows. Some Buddhists have also raised objections to the spending of so much money, all of it donated by local followers, to glorify the religious beliefs and protect the cultural artifacts of other people.

"If I had been building a temple, hospital or even a bridge, it would have been easy," explains Master Hsin Tao (心道法師), Wusheng's abbot. "But because I want to spend money presenting the glories of other religions as well as Buddhism, some people opposed the project."

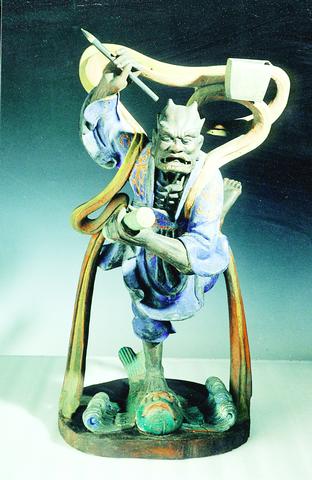

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE MUSEUM OF WORLD RELIGIONS

Inclusive vision

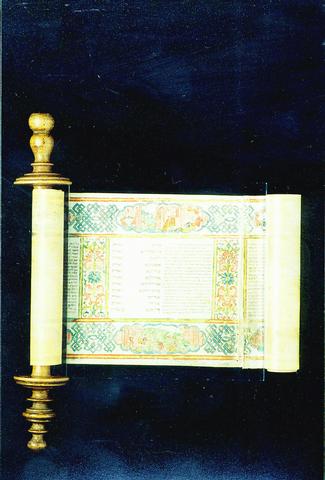

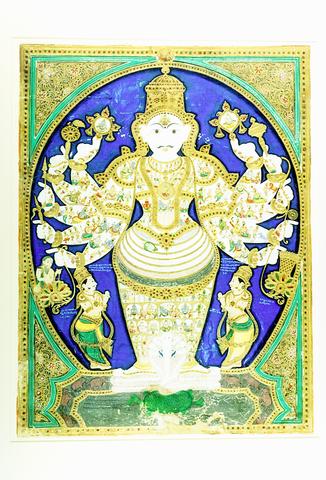

The Museum of World Religions started as a collection of Buddhist artifacts and items relating to Taiwan's popular religious practices. It now claims to evenhandedly present "the world's 10 major religions" chosen by size and antiquity. These are Hinduism, Shinto, Judaism, Taoism, Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, Sikhism, ancient religions (initially represented by Egypt) and indigenous religions represented by Mayan beliefs.

While the museum may be the most obvious evidence of Hsin Tao's ecumenical world vision, a trip to his mountain retreat will confuse anyone expecting a traditional zen dojo. Mahayana images, such as an Eleven-faced Bodhisattva statue on the summit, appear next to Thai and Burmese-style Hinayana stupas, Tibetan prayer flags and prayer wheels, Taoist bwey (筊) divination blocks and even Jewish and Egyptian symbols. At weekend meditation classes, the instructor may well be a Tibetan lama, Myanmar monk or Vissipana teacher.

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE MUSEUM OF WORLD RELIGIONS

Such an approach has made Hsin Tao unpopular among some who feel he risks diluting traditional ideas. There may also be a measure of envy in his detractors, as this "broad church" has attracted a following of hundreds of thousands.

"I am drawn by Master Hsin Tao's warmth and love," says a woman surnamed Dai (戴), who is a fairly typical member of Hsin Tao's following. Normally worshiping at the Taoist Lungshan Temple (龍山寺) in Taipei, she occasionally visits the Buddhist monastery, walking the last few kilometers up Lingjiou Mountain to spend the day among the stupas, prayer flags and sea breezes.

Love is Hsin Tao's by-word (his name means "way of the heart") -- the core of his own awakening seems to be that "love is the common ground of religions" -- and the Museum of World Religions has the slogan "Love is Our Shared Truth; Peace is Our Eternal Hope" translated into 14 languages in its lobby.

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE MUSEUM OF WORLD RELIGIONS

"Master Hsin Tao is not a scholar like, say, Master Sheng Yen (聖嚴) of the Dharma Drum organization (法鼓山), and he knows so," says Elise DeVido, secretary-general of the Ricci Institute for Chinese Studies in Taipei, who is engaged in a long-term study of the massive increase in Taiwan's female monastic population, currently estimated at around 75 percent of Taiwan's 30,000 monks and nuns.

"His legitimacy comes from his period of ascetic practice," she says, referring to the decade Hsin Tao spent "dwelling in silence among graves" after dropping out of a Buddhist seminary.

"He has two very different groups of followers. First, there are the tens of thousands of o-ba-san, middle- and working-class housewives practicing a folk brand of Buddhism. Many of these credit him with magical powers. Alongside these are large numbers of highly educated women." There are a number of famous people, too. Politicians, entrepreneurs, TV presenters, film and music stars have all made their way to Hsin Tao's hilltop retreat.

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE MUSEUM OF WORLD RELIGIONS

Former president Lee Teng-hui (李登輝) cut the first sod when the Buddhist foundation held a ground-breaking ceremony for the museum in 1995. Last year, Vice President Annette Lu (呂秀蓮) invited Hsin Tao to accompany her as cultural emissary on her visit to El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala.

He has also been feted by the international interfaith movement, delivering a lecture on Buddhism in the 21st century to the Parliament of World Religions in 1999 and another on conflict resolution to the UN Millennium Summit of Religious and Spiritual Leaders in 2000.

The backbone of his organization are the lay followers, however.

PHOTO COURTESY OF LING JIOU MOUNTAIN BUDDHIST FOUNDATION

"I was taken to Lingjiou Mountain by my boyfriend's mother in 1987," explains Rita Liu, a 30-something volunteer who has helped out at the Wusheng Monastery off and on ever since. "I wasn't even a Buddhist at that time.

"What particularly drew me to Master Hsin Tao was his immense kindness and the deep meaning he encapsulated in simple phrases." Her description is typical as the growth in his followers comes largely through personal contact and word of mouth rather than through published tracts or publicity stunts.

A large percentage of Lingjiou's early monastics came straight from university.

One such monastic was Shih Liao-yi (釋了意), who was tonsured in 1985. "As a student at Tamkang University I heard about a monk living in a cave near Fulung. I started visiting at weekends, spending more and more time in the company of this wise and peaceful monk. When he spoke, he seemed to speak to the real me that no one else recognized."

Nothing much has changed. Shih Hong-chih (釋鴻持), who left home at the end of last year to enter monastic life at the Wusheng Monastery, says, "Although the setting here is very tranquil and beautiful, the reason I chose to come was Master Hsin Tao. His heart is as broad as the sky."

Growing appeal

Hsin Tao's organization and followers are somewhat different from the other four main Buddhist groups in Taiwan. DeVido says Hsin Tao is not particularly intellectual, which distinguishes him from the leaders of the Dharma Drum Mountain (法鼓山教團) and Chung Tai Chan Monastery (中台禪寺教團) religious groups, which appeal largely to the educated and affluent, and have grown by organizing Zen meditation courses and retreats for urban white-collar workers.

Nor did he establish a one-stop theme park-style monastery like Buddha Light (佛光山), or a strongly regimented and hierarchical organization like Tzu-Chi (慈濟).

Although Hsin Tao arrived on the the scene somewhat later than these "big four," his organization is rapidly catching up.

The main reason for Hsin Tao's group's growing attraction is his charisma. In this, Hsin Tao is typical of the zen tradition, which traces its "transmission of the dharma" from enlightened teacher to disciple, and ultimately back to the Shakyamuni Buddha himself.

Although providing strong leadership and "brand recognition," this also means that the organization revolves largely around one person's reputation and has occasionally come under pressure as a consequence. At 53, Hsin Tao is much younger than the leaders of other monastic communities in Taiwan, but the question of succession, when it arises, will be a major challenge for his group.

Hopefully by that time the Museum of World Religions and the Commission for Preservation of Sacred Sites will have taken firm and independent roots of their own.

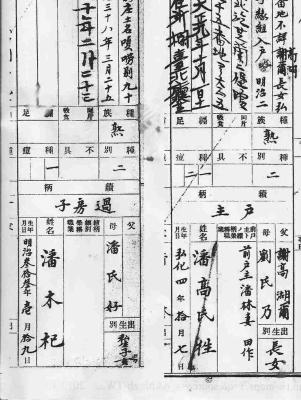

Feb. 9 to Feb.15 Growing up in the 1980s, Pan Wen-li (潘文立) was repeatedly told in elementary school that his family could not have originated in Taipei. At the time, there was a lack of understanding of Pingpu (plains Indigenous) peoples, who had mostly assimilated to Han-Taiwanese society and had no official recognition. Students were required to list their ancestral homes then, and when Pan wrote “Taipei,” his teacher rejected it as impossible. His father, an elder of the Ketagalan-founded Independence Presbyterian Church in Xinbeitou (自立長老會新北投教會), insisted that their family had always lived in the area. But under postwar

In 2012, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) heroically seized residences belonging to the family of former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁), “purchased with the proceeds of alleged bribes,” the DOJ announcement said. “Alleged” was enough. Strangely, the DOJ remains unmoved by the any of the extensive illegality of the two Leninist authoritarian parties that held power in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Taiwan. If only Chen had run a one-party state that imprisoned, tortured and murdered its opponents, his property would have been completely safe from DOJ action. I must also note two things in the interests of completeness.

Taiwan is especially vulnerable to climate change. The surrounding seas are rising at twice the global rate, extreme heat is becoming a serious problem in the country’s cities, and typhoons are growing less frequent (resulting in droughts) but more destructive. Yet young Taiwanese, according to interviewees who often discuss such issues with this demographic, seldom show signs of climate anxiety, despite their teachers being convinced that humanity has a great deal to worry about. Climate anxiety or eco-anxiety isn’t a psychological disorder recognized by diagnostic manuals, but that doesn’t make it any less real to those who have a chronic and

When Bilahari Kausikan defines Singapore as a small country “whose ability to influence events outside its borders is always limited but never completely non-existent,” we wish we could say the same about Taiwan. In a little book called The Myth of the Asian Century, he demolishes a number of preconceived ideas that shackle Taiwan’s self-confidence in its own agency. Kausikan worked for almost 40 years at Singapore’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, reaching the position of permanent secretary: saying that he knows what he is talking about is an understatement. He was in charge of foreign affairs in a pivotal place in