First it sold books. Then it added gadgetry, groceries and chipper virtual assistants — but Amazon.com Inc’s latest expansion will take many shoppers by surprise.

Meet Amazon, aspiring military behemoth.

In the not too distant future, US soldiers might rely on Amazon-run systems to trade intelligence, relay orders and call for help. Drone footage might be scoured for wanted men and women by Amazon software. Defense department quartermasters would use Amazon technology to move ammunition and supplies.

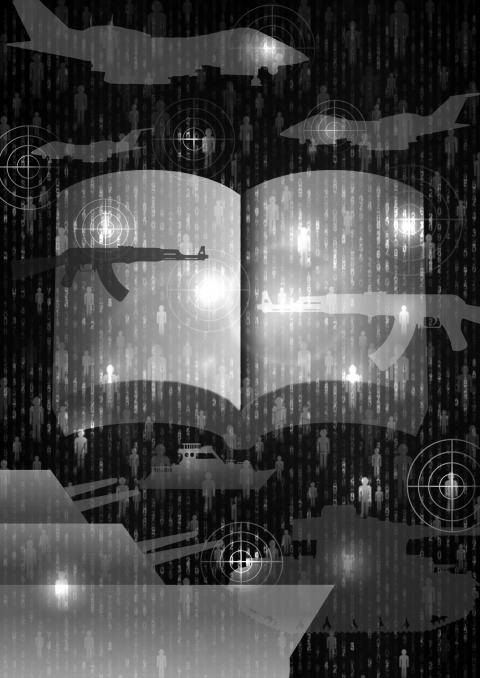

Illustration: Yusha

For Amazon chief executive Jeff Bezos, it is not a question of whether customers will mind his company’s defense ambitions, or of complaints raised by civil liberties advocates. As Amazon’s face and founder casts it, the issue is one of patriotism.

“This is a great country and it does need to be defended,” Bezos said during an October Wired magazine summit. “If big tech companies are going to turn their back on the US Department of Defense, this country is going to be in trouble.”

Now Amazon is the leading contender for a 10-year, US$10 billion project to accelerate the Pentagon’s move into cloud computing.

The department has said that the goal of the Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure — widely known by its Star Wars-styled acronym, JEDI — is to increase the US’ “lethality” by replacing its antiquated, segmented information technology systems.

Amazon is widely regarded as the strongest contender for the JEDI contract, which is expected to be inked in the first half of the year, in part because its division Amazon Web Services (AWS) already dominates cloud computing in the US.

One 2017 estimate found that AWS held more than half of the worldwide cloud computing market. AWS hosts top-secret data for the CIA, supports federal agencies from the US Department of Justice to NASA, powers the US’ national immigration case management system and stores hundreds of millions of identity documents.

JEDI is expected to inject modern technology into a creaky system. An audit in November last year found that “systemic flaws” in defense department networks invite hacking and that the department’s finance systems were so disorganized that they could not be audited.

JEDI is a first step toward a system that will handle tasks as diverse as frontline communications, medical records management and scheduling.

The finished system is to move petabytes of data between every continent except Antarctica. Service members at the “tactical edge” are to be equipped with rugged devices enabling them to check into the cloud. Modular data centers are to be deployed to forward bases. The Pentagon hopes those can operate in space.

If Amazon wins the JEDI contract and another contract to open a government e-commerce portal, the company would “vault from being a bit player to becoming one of the 10 most dominant federal contractors, with potential to become one of the largest in relatively short order,” said Steven Schooner, a professor of government procurement law at George Washington University.

Amazon makes no apologies for moving aggressively into the public sector in this way.

“We feel strongly that the defense, intelligence and national security communities deserve access to the best technology in the world and we are committed to supporting their critical missions of protecting our citizens and defending our country,” a spokesperson for the Seattle-based company said in response to a request for comment.

The proposition that Amazon should defend the US can be seen as a logical extension of a mission Bezos laid down in a 1997 letter to shareholders. Amazon targets dysfunctional systems that are not serving customers well — from book distribution, to home delivery to computer networking — and leads their reinvention.

“We will continue to focus relentlessly on our customers,” Bezos wrote. “We will make bold, rather than timid investment decisions where we see a sufficient probability of gaining market leadership advantages.”

Bezos is not the first in his family in the defense sector. His formative influences included his grandfather Lawrence Preston Gise, who is usually described in media accounts as Bezos would have known him — a semiretired rancher showing his grandson how to castrate bulls.

Yet Gise also made his living as a defense researcher and manager during the early days of the Cold War and ultimately ran the New Mexico office of the US Atomic Energy Commission, which was in charge of the US’ civilian and military nuclear programs until the 1970s.

Big tech and the defense industry have been intertwined since World War II, when military funding financed the development of the first all-digital computers, said Margaret O’Mara, a University of Washington history professor.

That connection deepened as defense money flowed to researchers developing software languages, networks, machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI), she said.

“You name it, there’s some defense DNA in there somewhere,” O’Mara said.

AWS made a splash in national security circles in 2013 when it launched a US$600 million cloud network for the CIA and other US intelligence agencies.

John Wood, the CEO of Telos, a Virginia-based cybersecurity firm, likened the contract to the “shot heard ‘round the world.”

“The CIA, arguably the most security conscious organization in the world, decided that they were going to move to the cloud,” Wood said. “That really made the rest of the world stand up and take notice, and ask the question: ‘If it’s good enough for them, why isn’t it good enough for us?’”

Dozens of agencies — from the FBI to the US Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, to the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency — are now AWS users.

Critics worry both that a “cloud-industrial complex” is forming as large tech companies wade into national security and that rapidly developing technologies could be misused by the military or police. AI-assisted facial recognition software has been an early flashpoint.

Amazon’s move to sell its facial recognition software, Rekognition, to US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) prompted protest from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), a small group of shareholders and about a 100 employees. Bezos was not deterred. AWS sales teams have also pitched Rekognition at defense industry events.

Amazon declined to say which agencies, if any, are using Rekognition. However, it is clear to observers that AWS has the desire to make money off defense and law enforcement customers.

“They’ve been consistent in selling these technologies at trade shows,” said Shankar Narayan of the Washington state affiliate of the ACLU, which in January demanded that Amazon, Alphabet Inc’s Google and Microsoft Corp stop selling artificial intelligence-assisted facial recognition to the US government.

“They demoed it to ICE. The FBI is testing it,” he said.

Amazon asserts that Rekognition can spot Kalashnikovs and faces from a user-selected watch list in near real-time. Image recognition software greatly speeds the review of surveillance footage.

Speaking at an Amazon-organized conference last year, FBI Deputy Assistant Director for Counterterrorism Christine Halvorsen said that analysts combing video of the 2017 Las Vegas massacre could have completed their work in a day if they had access to Rekognition.

Instead, it took weeks to track the shooter’s movements, she said.

Microsoft and Google have, to varying degrees, recognized civil liberties and human rights concerns raised by the new technology. Amazon has largely declined to address the moral dimensions of national security work.

“Amazon really has distinguished themselves as being an actor that doesn’t acknowledge any responsibility and really has doubled down on selling these technologies to the government, the military, as well as law enforcement,” Narayan said.

The company “has largely hewed to the position that their founder has articulated, that society supposedly has this ‘immune response’ to new technologies like these and things will get sorted out on their own,” he said. “That’s an attitude that rests on a great deal of privilege and doesn’t really account for the human lives that are being impacted by this technology in real time.”

Amazon is widely regarded as the strongest contender for the JEDI contract. Competition for JEDI has been bitter. Amazon’s rivals — Oracle Corp, International Business Machines Corp and Microsoft — have protested, unsuccessfully thus far, contract requirements that they claim unfairly favor Amazon.

Oracle, a California tech giant, sued the US federal government in December last year. Attorneys for Oracle suggested that defense department employees with connections to AWS biased the contract in Amazon’s favor.

AWS general manager Deap Ubhi spent a year as a product director for the US Defense Digital Service, a Pentagon’s tech division. The defense department is currently reviewing Ubhi’s work developing the JEDI contract.

The awarding of the contract could reverberate.

It could give the winner a lasting advantage in US government cloud computing — “a monopoly over this area for years to come,” said Neil Gordon of the Project On Government Oversight, a US watchdog group examining federal contracting.

In the first year of his second term, US President Donald Trump continued to shake the foundations of the liberal international order to realize his “America first” policy. However, amid an atmosphere of uncertainty and unpredictability, the Trump administration brought some clarity to its policy toward Taiwan. As expected, bilateral trade emerged as a major priority for the new Trump administration. To secure a favorable trade deal with Taiwan, it adopted a two-pronged strategy: First, Trump accused Taiwan of “stealing” chip business from the US, indicating that if Taipei did not address Washington’s concerns in this strategic sector, it could revisit its Taiwan

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) challenges and ignores the international rules-based order by violating Taiwanese airspace using a high-flying drone: This incident is a multi-layered challenge, including a lawfare challenge against the First Island Chain, the US, and the world. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) defines lawfare as “controlling the enemy through the law or using the law to constrain the enemy.” Chen Yu-cheng (陳育正), an associate professor at the Graduate Institute of China Military Affairs Studies, at Taiwan’s Fu Hsing Kang College (National Defense University), argues the PLA uses lawfare to create a precedent and a new de facto legal

The stocks of rare earth companies soared on Monday following news that the Trump administration had taken a 10 percent stake in Oklahoma mining and magnet company USA Rare Earth Inc. Such is the visible benefit enjoyed by the growing number of firms that count Uncle Sam as a shareholder. Yet recent events surrounding perhaps what is the most well-known state-picked champion, Intel Corp, exposed a major unseen cost of the federal government’s unprecedented intervention in private business: the distortion of capital markets that have underpinned US growth and innovation since its founding. Prior to Intel’s Jan. 22 call with analysts

Chile has elected a new government that has the opportunity to take a fresh look at some key aspects of foreign economic policy, mainly a greater focus on Asia, including Taiwan. Still, in the great scheme of things, Chile is a small nation in Latin America, compared with giants such as Brazil and Mexico, or other major markets such as Colombia and Argentina. So why should Taiwan pay much attention to the new administration? Because the victory of Chilean president-elect Jose Antonio Kast, a right-of-center politician, can be seen as confirming that the continent is undergoing one of its periodic political shifts,