On Wednesday last week, China successfully landed its Chang’e 4 spacecraft on the moon’s far side — an impressive technological accomplishment that speaks to China’s emergence as a major space power.

Understandably, some Chinese scientists are taking a victory lap, with one going so far as to gloat to the New York Times that: “We Chinese people have done something that the Americans have not dared try.”

That cockiness speaks to the spirit of great-power competition animating the Chinese space program. China is open about the fact that it is not merely looking to expand human knowledge and boundaries; it is hoping to supplant the US as the 21st century’s dominant space power.

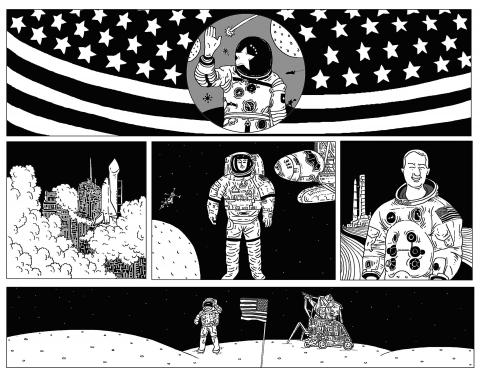

Illustration: Mountain People

If this were still the 1960s, when the US and Soviet space agencies fiercely competed against one another, China’s deep pockets, focus and methodical approach to conquering the heavens might indeed win the day.

However, the truth is, thanks to the development of a dynamic, fast-moving US commercial space industry, China’s almost certain to be a runner-up for decades to come.

That does not mean the People’s Republic of China is not making progress in its attempts to colonize the moon and turn it into the outer space equivalent of its South China Sea outposts — an avowed goal of Ye Peijian (葉培建), head of China’s lunar program.

China is to launch a mission to bring back samples from the moon later this year. Over the next decade, it plans to launch a space station, a Mars probe, asteroid missions and a Jupiter probe, while continuing to develop reusable rockets and other vehicles that would enhance its access to space. A human mission to the moon is targeted for 2030 and a permanent colony by the middle of the century.

By contrast, NASA’s own ambitions seem limited. US astronauts have not left low-Earth orbit since the last Apollo moon landing in 1972, while the US lost the ability to fly to the taxpayer-funded International Space Station with the retirement of the space shuttle.

Too often, new US presidents have shifted space priorities, forcing NASA to cancel or reconfigure expensive missions that have been years in the planning. Worse, many members of US Congress still view NASA as a tool to deliver wasteful, pork-barrel spending to politically connected constituencies.

However, that hardly describes the entirety of the US space program. Since the mid-2000s, when Congress authorized the agency to begin cultivating public-private partnerships, NASA’s most important role has been as a seed investor and adviser to private space companies.

While Elon Musk’s Space Exploration Technologies Corp — or SpaceX — receives the bulk of attention, the commercial space industry now comprises dozens of firms in fields ranging from small satellites to lunar exploration.

The results have been spectacular: By NASA’s own estimates, the cost of SpaceX developing its workhorse Falcon 9 rocket was less than 10 percent of what it would have cost if NASA had done it.

NASA’s backing is paying dividends elsewhere, too. In coming weeks, SpaceX is to launch uncrewed orbital test flights of its Crew Dragon spacecraft — a capsule designed to deliver US astronauts to the International Space Station.

At least two other companies are looking to launch commercial space stations.

Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin is planning an uncrewed moon landing by 2023 (in line with NASA’s lunar goals). Meanwhile, SpaceX is developing a larger rocket that is scheduled to take tourists around the moon that same year. And NASA, keen to encourage more lunar exploration, has announced a partnership with nine companies developing lunar landers, with the first missions set to launch as early as this year.

Of course, space exploration is not just about making money and colonizing the moon. Science, too, remains a motivation and there the US remains a global leader with a nearly insurmountable lead.

Last week, the New Horizons probe completed the most distant exploration in history (of a small rock 6.4 billion kilometers from Earth) and the OSIRIS-REx probe went into orbit around a small asteroid (that it is to sample next year).

NASA also has — among other missions — one ongoing mission at Jupiter and four at Mars, a solar probe and two spacecraft that have entered interstellar space.

Neither China nor any other country has plans to compete with this record of accomplishment, nor do they have the scientific or engineering experience to do so.

As long as the US remains focused on cultivating its commercial space industry and continuing to fund cutting-edge science programs, it has little reason to fear falling behind. Better yet, it has a much better chance to attract space scientists and other talent keen to profit from one of the 21st century’s most promising growth industries.

China, too, is not oblivious to the potential of commercial space — it is developing its own industry — but the persistent dominance of China’s state sector ensures that its entrepreneurs would spend as much time on politics as propulsion systems. If there is a new race to the stars, the US remains a good bet to win.

Jan. 1 marks a decade since China repealed its one-child policy. Just 10 days before, Peng Peiyun (彭珮雲), who long oversaw the often-brutal enforcement of China’s family-planning rules, died at the age of 96, having never been held accountable for her actions. Obituaries praised Peng for being “reform-minded,” even though, in practice, she only perpetuated an utterly inhumane policy, whose consequences have barely begun to materialize. It was Vice Premier Chen Muhua (陳慕華) who first proposed the one-child policy in 1979, with the endorsement of China’s then-top leaders, Chen Yun (陳雲) and Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平), as a means of avoiding the

The last foreign delegation Nicolas Maduro met before he went to bed Friday night (January 2) was led by China’s top Latin America diplomat. “I had a pleasant meeting with Qiu Xiaoqi (邱小琪), Special Envoy of President Xi Jinping (習近平),” Venezuela’s soon-to-be ex-president tweeted on Telegram, “and we reaffirmed our commitment to the strategic relationship that is progressing and strengthening in various areas for building a multipolar world of development and peace.” Judging by how minutely the Central Intelligence Agency was monitoring Maduro’s every move on Friday, President Trump himself was certainly aware of Maduro’s felicitations to his Chinese guest. Just

A recent piece of international news has drawn surprisingly little attention, yet it deserves far closer scrutiny. German industrial heavyweight Siemens Mobility has reportedly outmaneuvered long-entrenched Chinese competitors in Southeast Asian infrastructure to secure a strategic partnership with Vietnam’s largest private conglomerate, Vingroup. The agreement positions Siemens to participate in the construction of a high-speed rail link between Hanoi and Ha Long Bay. German media were blunt in their assessment: This was not merely a commercial win, but has symbolic significance in “reshaping geopolitical influence.” At first glance, this might look like a routine outcome of corporate bidding. However, placed in

China often describes itself as the natural leader of the global south: a power that respects sovereignty, rejects coercion and offers developing countries an alternative to Western pressure. For years, Venezuela was held up — implicitly and sometimes explicitly — as proof that this model worked. Today, Venezuela is exposing the limits of that claim. Beijing’s response to the latest crisis in Venezuela has been striking not only for its content, but for its tone. Chinese officials have abandoned their usual restrained diplomatic phrasing and adopted language that is unusually direct by Beijing’s standards. The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs described the