The most recent WTO ministerial conference, held last month in Buenos Aires, Argentina, was a fiasco. Despite a limited agenda, the participants were unable to produce a joint statement.

However, not everyone was disappointed by that outcome: China maintained a diplomatic silence, while the US seemed to celebrate the meeting’s failure. This is bad news for Europe, which was virtually alone in expressing its discontent.

It is often pointed out that, in the face of US President Donald Trump’s blinkered protectionism, the EU has an opportunity to assume a larger international leadership role, while strengthening its own position in global trade.

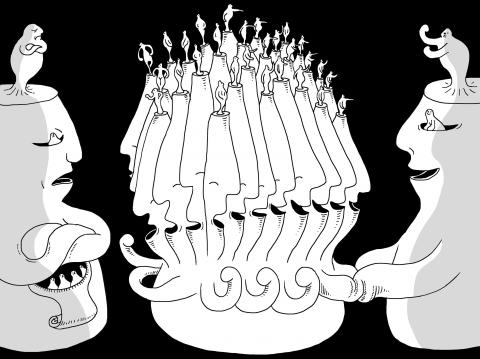

Illustration: Mountain People

The free-trade agreement recently signed with Japan will give the EU a clear advantage over the US in agriculture and strengthening trade ties with Mexico could have a similar effect, as the US renegotiates the North American Free Trade Agreement.

Some suggest that, to strengthen its position further, Europe should team up with China, which, despite its reticence at the WTO conference, has lately attempted to position itself as a champion of multilateralism.

A Sino-European partnership could be a powerful force offsetting the US’ negative impact on international trade and cooperation.

Yet such a partnership is far from certain. Yes, Europe and China converge on a positive overall view of globalization and multilateralism. However, whereas Europe supports a kind of “offensive multilateralism” that seeks to beef up existing institutions’ rules and enforcement mechanisms, China resists changes to existing standards, especially if they strengthen enforcement of rules that might constrain its ability to maximize its own advantages.

Europe’s desire to force China to adhere to common rules aligns its interests more closely with the US, with which it shares many of the same grievances, from China’s continued subsidization of private enterprises to the persistence of barriers to market access.

According to one recent study, market access barriers erected by China have taken a high toll on the growth of EU exports.

However, the US and the EU do not have the same vision for how to address these grievances. To limit abuse of WTO rules by China, Europe’s leaders want to be able to negotiate new, clearer rules, either through the framework of a bilateral investment agreement or through a plurilateral agreement on public procurement.

Trump does not want to reform the system; he wants to sink it. In fact, with Trump seeking to use bilateral deals to secure reductions in the US’ trade deficit, the possibility that the US will leave the WTO altogether — a nightmare scenario for the EU, which advocates shared norms over force — cannot be excluded.

Trump’s predecessor, former US president Barack Obama, had his own solution. New multilateral frameworks — the Trans-Pacific Partnership with Asia and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) with the EU — would circumscribe China’s room for maneuver.

As such frameworks brought about regulatory convergence, the US and the EU would be able to define the standards of the emerging new global economy, forcing China either to accept those standards or be left behind.

However, this project has now been fatally undermined. Obama’s effort to finalize both agreements before the end of his presidency, though understandable, bred serious concerns about hastiness.

Europeans recognized that full regulatory convergence between the US and the EU would, in reality, take at least a decade. So, under pressure from their citizens, European leaders began to express concern about what the TTIP was lacking in terms of environmental and sanitary regulations and transparency.

Given their shared interest in regulatory convergence, particularly to strengthen their position vis-a-vis China, the US and the EU will eventually have to resume cooperation toward that end.

However, as long as Trump is in power, advocating bilateral reciprocity over multilateralism, such an effort will probably be impossible.

Instead, Trump’s US will most likely continue to take advantage of its far-reaching commercial influence to secure strategic or political gains. On this front, Europe is at a significant disadvantage. The EU is, after all, not a state, and it does not speak on international matters with one voice.

It is not out of the question that the Chinese, who speak the language of realpolitik fluently, would prefer to meet the ad hoc demands of the Americans over the multilateral conditions of the Europeans.

In this context, the EU’s top priority should be to unify the positions of its member states, with the goal of overcoming the barriers erected by the US and creating shared systems for constraining China.

However, that is easier said than done. As it stands, many EU countries resist the introduction of any trade restrictions, whether owing to an excessive commitment to liberal economic ideals or fear of jeopardizing their own interests in China by establishing an EU mechanism for managing foreign investment.

The emergence of “illiberal” governments in Central and Eastern Europe complicates matters further for the EU. These governments have no interest in any form of multilateralism, as they have embraced a narrow view of their interests. They often seem fascinated by the logic of realpolitik espoused by Trump, Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) and Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Moreover, these countries’ pursuit of their commercial interests could come at the expense of EU procurement rules, and they are not alone within the EU.

Greece, for example, has accepted large amounts of Chinese investment. The EU then refused to mention China explicitly in a resolution on the conflict in the South China Sea.

To be sure, European countries are not wrong to welcome Chinese investment. However, China should be reciprocating, offering European investment in China a warmer welcome.

That is why the EU and China should work to complete the bilateral investment treaty that they have been negotiating for years, with limited progress. Such a treaty should rely on reciprocal rules, including the dismantling of barriers to China’s market.

French President Emmanuel Macron is trying to advance offensive multilateralism.

However, unless the EU as a whole embraces the cause, Europe — caught between China, which has a very conservative, but outdated interpretation of multilateralism, and Trump, who wants to get rid of it — risks becoming a casualty.

Zaki Laidi, a professor of international relations at L’Institut d’etudes politiques de Paris (Sciences Po), was an adviser to former French prime minister Manuel Valls.

Copyright: Project Syndicate 2018

The conflict in the Middle East has been disrupting financial markets, raising concerns about rising inflationary pressures and global economic growth. One market that some investors are particularly worried about has not been heavily covered in the news: the private credit market. Even before the joint US-Israeli attacks on Iran on Feb. 28, global capital markets had faced growing structural pressure — the deteriorating funding conditions in the private credit market. The private credit market is where companies borrow funds directly from nonbank financial institutions such as asset management companies, insurance companies and private lending platforms. Its popularity has risen since

The Donald Trump administration’s approach to China broadly, and to cross-Strait relations in particular, remains a conundrum. The 2025 US National Security Strategy prioritized the defense of Taiwan in a way that surprised some observers of the Trump administration: “Deterring a conflict over Taiwan, ideally by preserving military overmatch, is a priority.” Two months later, Taiwan went entirely unmentioned in the US National Defense Strategy, as did military overmatch vis-a-vis China, giving renewed cause for concern. How to interpret these varying statements remains an open question. In both documents, the Indo-Pacific is listed as a second priority behind homeland defense and

Every analyst watching Iran’s succession crisis is asking who would replace supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Yet, the real question is whether China has learned enough from the Persian Gulf to survive a war over Taiwan. Beijing purchases roughly 90 percent of Iran’s exported crude — some 1.61 million barrels per day last year — and holds a US$400 billion, 25-year cooperation agreement binding it to Tehran’s stability. However, this is not simply the story of a patron protecting an investment. China has spent years engineering a sanctions-evasion architecture that was never really about Iran — it was about Taiwan. The

In an op-ed published in Foreign Affairs on Tuesday, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairwoman Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) said that Taiwan should not have to choose between aligning with Beijing or Washington, and advocated for cooperation with Beijing under the so-called “1992 consensus” as a form of “strategic ambiguity.” However, Cheng has either misunderstood the geopolitical reality and chosen appeasement, or is trying to fool an international audience with her doublespeak; nonetheless, it risks sending the wrong message to Taiwan’s democratic allies and partners. Cheng stressed that “Taiwan does not have to choose,” as while Beijing and Washington compete, Taiwan is strongest when