US President Donald Trump’s talk of a “military option” in Venezuela risks alienating Latin American nations that overcame their reluctance to work with the Republican leader and had adopted a common, confrontational approach aimed at isolating Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro’s embattled government.

Well before Maduro himself responded, governments in Latin America with a long memory of US interventions were quick to express alarm over what sounded to them like saber-rattling.

Even Colombia — Washington’s staunchest ally in the region — condemned any “military measures and the use of force” that encroach on Venezuela’s sovereignty.

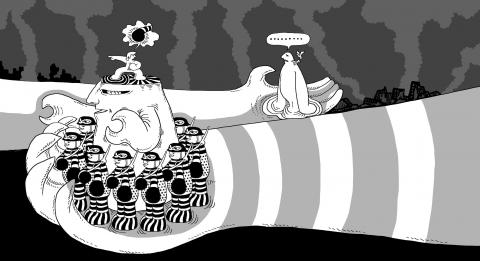

Illustration: Mountain people

Maduro has long accused Washington of having military designs on Venezuela and specifically its vast oil reserves.

However, those claims were dismissed by many as an attempt to distract from his government’s failures to curb problems such as widespread shortages, spiraling inflation and one of the world’s worst homicide rates.

“For years he’s been saying the US is preparing an invasion and everyone laughed, but now the claim has been validated,” said Mark Feierstein, who served as former US president Barack Obama’s top national security adviser on Latin America. “It’s hard to imagine a more damaging thing for Trump to say.”

The timing of Trump’s remarks could not be worse, coming on the eve of a four-nation Latin America trip by US Vice President Mike Pence intended to showcase how Washington and regional partners can work to promote democracy.

This week in Peru, foreign ministers from 12 Western nations condemned the breakdown of democracy in Venezuela and refused to recognize a new, pro-government assembly created by Maduro that is charged with rewriting the Venezuelan constitution, but is seen by many as an illegitimate power grab.

The US did not take part in the meeting, a show of deference to countries historically mistrustful of heavy-handed policies out of Washington.

Suspicion and resentment linger in many corners of the region, a reflection of years past when US troops did in fact invade parts of Latin America to oust leftist leaders or collect unpaid debts.

Yet a number of leaders, amid prodding from the Trump administration, have lately been overcoming their reluctance to intervene in a neighbor’s internal political affairs after looking the other ways for years on Venezuela.

For the first time, leaders have started using the D-word — dictatorship — to describe Venezuela’s government and have recalled their ambassadors from Caracas in protest.

Peru on Friday went so far as to expel Venezuela’s ambassador and last week the South American trade bloc Mercosur suspended Venezuela for breaches of the group’s democratic norms.

Even more surprising, with the exception of close ideological allies such as Cuba and Bolivia, no country spoke out against Trump’s decision to slap sanctions on more than 30 Venezuelan officials, including Maduro himself, despite past criticism of similar unilateral actions.

Not even the frustration over Trump’s decision to partially roll back Obama’s opening to Cuba — a diplomatic thaw that was applauded across the region’s political spectrum — or his constant talk of building a border wall to keep out immigrants got in the way of presenting a united front toward Maduro.

However, the swift reaction to Trump’s “military” remarks shows there is no appetite in the region for US troops to get involved.

On Saturday the nations of Mercosur, which includes Brazil and Argentina, issued a statement saying: “The only acceptable means of promoting democracy are dialogue and diplomacy” and repudiating “violence and any option that implies the use of force.”

US engagement with other countries has not been constant and may have benefited more from the deteriorating situation in Venezuela than any concerted diplomatic outreach.

US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson in June skipped a key meeting of the Organization of American States, depriving some Caribbean countries that depend on Venezuelan oil shipments of the political cover they were looking for to abandon their support for Maduro.

Under the advice of Pence and Republican Senator Marco Rubio, Trump appears to have taken an interest in Venezuela and even met at the White House with the wife of a prominent jailed opposition leader.

That in turn has emboldened Maduro opponents, who have been protesting for four months demanding he give up power.

Their efforts could be undermined if Maduro expands his crackdown on dissent, arguing as he has in the past that their tactics are a prelude to a US-backed coup.

Only this time he can point to Trump’s words as evidence.

Pence arrived in Colombia on Sunday to begin his Latin America tour, during which discussions on how to deal with Venezuela are expected to feature prominently.

Instead he might be forced to do damage control, said Christopher Sabatini, executive director of Global Americans, a Web site focused on US policy in the region.

“He’s about to get an earful,” Sabatini said. “The eagerness of Trump and some people around him to mouth off without any idea of context is really damaging not only to US policy, but also regional stability.”

There is a modern roadway stretching from central Hargeisa, the capital of Somaliland in the Horn of Africa, to the partially recognized state’s Egal International Airport. Emblazoned on a gold plaque marking the road’s inauguration in July last year, just below the flags of Somaliland and the Republic of China (ROC), is the road’s official name: “Taiwan Avenue.” The first phase of construction of the upgraded road, with new sidewalks and a modern drainage system to reduce flooding, was 70 percent funded by Taipei, which contributed US$1.85 million. That is a relatively modest sum for the effect on international perception, and

When former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) first took office in 2016, she set ambitious goals for remaking the energy mix in Taiwan. At the core of this effort was a significant expansion of the percentage of renewable energy generated to keep pace with growing domestic and global demands to reduce emissions. This effort met with broad bipartisan support as all three major parties placed expanding renewable energy at the center of their energy platforms. However, over the past several years partisanship has become a major headwind in realizing a set of energy goals that all three parties profess to want. Tsai

An elderly mother and her daughter were found dead in Kaohsiung after having not been seen for several days, discovered only when a foul odor began to spread and drew neighbors’ attention. There have been many similar cases, but it is particularly troubling that some of the victims were excluded from the social welfare safety net because they did not meet eligibility criteria. According to media reports, the middle-aged daughter had sought help from the local borough warden. Although the warden did step in, many services were unavailable without out-of-pocket payments due to issues with eligibility, leaving the warden’s hands

At the end of last year, a diplomatic development with consequences reaching well beyond the regional level emerged. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared Israel’s recognition of Somaliland as a sovereign state, paving the way for political, economic and strategic cooperation with the African nation. The diplomatic breakthrough yields, above all, substantial and tangible benefits for the two countries, enhancing Somaliland’s international posture, with a state prepared to champion its bid for broader legitimacy. With Israel’s support, Somaliland might also benefit from the expertise of Israeli companies in fields such as mineral exploration and water management, as underscored by Israeli Minister of